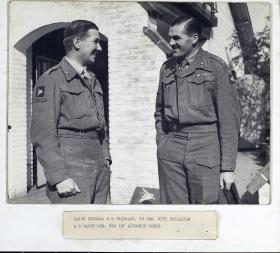

In 1943, the 1st Airborne Division found itself leaderless after Major-General Hopkinson was killed during the initial stages of their part in the invasion of Italy. The obvious successor, Brigadier Eric Down, was given temporary command before being sent to form an Airborne Division in India, but with few likely choices to replace him, the horrifying prospect of appointing a commander from outside the Airborne Forces became likely. One of the dangers of appointing a General not of their breed was that he might not fully appreciate how such a unit needed to operate. Lt-General Browning consented to this move so long as the choice was fresh from battle. Brigadier Robert "Roy" Urquhart, a 43 year old Scot, was chosen.

The hand-over was unusual to say the least. It was arranged that the generals should meet at the ‘In and Out’ – the Naval and Military Club – in Piccadilly, London. They had luncheon together, which took ninety minutes, and in that time the hand-over was completed. It is doubtful if any division, or any formation, had been handed over in this way before, or has been since. The Headquarters, 1st Airborne Division was located at Fulbeck Hall, Lincolnshire, which was some two hundred miles north of the Club in London. Roy Urquhart’s comment on the hand-over was, “It was a bit of a rush and I do not think that ‘Eric’ Down was best pleased on having to leave the 1st Airborne Division.”

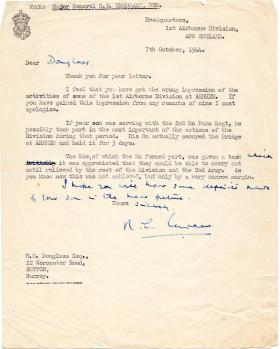

Born on 28 November 1901 in Shepperton, Middlesex, Urquhart had been educated at St Paul's and Sandhurst before being commissioned into the Highland Light Infantry in 1920, with whom he remained, stationed in India, until 1940. From 1941 to 1943, as a Lieutenant-Colonel, he had commanded the 2nd Battalion the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry before acting as Chief of Staff to the 51st Highland Division, serving in North Africa. Promoted to Brigadier, he led this Division's 231 Brigade Group with great success in Sicily and then Italy, where he was slightly wounded and awarded the DSO and Bar. Urquhart was appointed Brigadier General Staff to XII Corps of the 2nd British Army, and had only served in this capacity for a few months before being offered command of the 1st Airborne Division. This came as a great surprise to him as he had thought of the airborne movement as "a family business" that produced its own commanders, and he had no experience of this kind of warfare, nor had he given the slightest thought to it. He was highly aware of these facts but relished the opportunity of his first divisional command, and reasoned that once the airborne troops were on the ground, the rules of war that he was accustomed to were largely the same. Taking command of the Division on 7 January 1944, Urquhart had an uphill struggle to win the respect of his men, which he found quite unnerving as there was always a sense that his every movement was being monitored. Moreover those who were suspicious of his appointment made little attempt to disguise it, and one of his Brigadiers, probably Lathbury, had been unofficially informed that command of the Division would pass to him. John Frost said of Urquhart that he "was not a man to court popularity and, largely owing to the way the Division was dispersed all over Lincolnshire, we did not see him as much as we would have liked, but he very soon earned our complete respect and trust. In fact few generals have been so sorely tested and have yet prevailed." Sergeant Roy Hatch, a Glider Pilot, described the six foot, two hundred pound Scot as "a bloody general who didn't mind doing the job of a Sergeant." This was proved during the battle when he helped a signalman drag a heavy spare radio battery out of a storage trench and to the command trench. Not realizing that his helper was an officer, the man asked Urquhart to help him bring another, which he did without hesitation. It wasn't until they had finished their task that the signalman realized that his assistant was no less a man than the General. He offered his thanks, to which Urquhart modestly replied "That's all right, son". His unassuming and confident attitude won the respect of any doubters.

During the planning for Market Garden, Urquhart regarded it as the job of an airborne commander to get hold of as many transport aircraft as possible without sparing a thought for the other Divisions involved, and so he made a habit of lodging frequent requests with Corps HQ. One time he asked for a further 40 aircraft from Browning, who was doubtful that even a small number of these would materialize. Urquhart pointed out that the American airborne Divisions were receiving more than their fair share of aircraft, but Browning dissuaded him from thinking that this had anything to do with American political pressure, and correctly explained that the divisions were given priority depending on how close they were to the starting line. The US 101st Airborne were to deploy almost all of their infantry strength with the First Lift, because to do otherwise would increase the possibility of a vital bridge being lost and those divisions to the north becoming cut off and utterly destroyed. On Friday 15th, Urquhart was taking the opportunity to enjoy a round on the few holes still playable at Moor Park Golf Club, Corps HQ, when his Chief of Staff, Lt-Colonel Charles Mackenzie, put in an appearance to break the news that they were to lose some gliders on the First Lift. No explanation was given, but this was to enable Corps HQ to journey to Nijmegen. Urquhart insisted that whatever had to be left behind on the first day, anti-tank guns were not to be sacrificed. Despite the optimistic Intelligence reports stating that there was no substantial German armour in the region to threaten them, Urquhart did not wish to take a chance.

It has been opined that if he had been an experienced airborne commander, Urquhart may have been more determined to oppose the decision to land the whole Division 8 miles from the bridge, rather than drop the parachutists much closer to it. It is a point that those who knew the General would refute without difficulty. However it is true that his objection to the poor air plan could have been stronger than it was, but it must be remembered that Urquhart had to plan an entire operation in only seven days, and so when faced with stubborn opposition from fellow commanders he had little option but to accept the situation and move on. Nevertheless, these failings in the plan sealed the fate of Market Garden before it had begun.

Major-General Urquhart was not a trained parachutist and so flew to Arnhem by glider. When he first assumed command of the 1st Airborne he had suggested to Browning that he ought to become a parachutist, but casting an eye over his far from slender figure his Corps commander told him; "I shouldn't worry about learning to parachute. Your job is to prepare this division for the invasion of Europe. Not only are you too big for parachuting but you are also getting on". Urquhart actually loathed flying and feared he would get air sick on the way, but as it happened his mind was so preoccupied going over and over the plan that he was fine. The landing of his glider was safe and uneventful, and with no signs of immediate danger and little else to do at this early stage, he strolled over to the neighbouring drop zone to watch the spectacle of the 1st Para Brigade arrive. Urquhart was noted to be very pleased at the splendidly successful start to the battle.

It was not long before Divisional Signals discovered that their radio sets were not working correctly, or even at all. Urquhart could visibly see that the 1st Para Brigade and the Divisional Units were going about their business without problems, but the 1st Airlanding Brigade were out of sight on LZ-S, and so he set out in his Jeep to verify that they were alright. It was at the HQ of Brigadier Hicks that Urquhart had heard that the Reconnaissance Squadron was forced to abandon its coup-de-main attempt on the Bridge after running into Battalion's Krafft's blocking line. The 1st Para Brigade could not be contacted by radio, and so Urquhart, growing increasingly anxious and impatient, made the fateful and very dangerous decision to set out in his Jeep to find Brigadier Lathbury and warn him that no British force would be at the bridge when his men arrived. Lathbury was paying a call on the 3rd Battalion when Urquhart caught up with him, but a short time later the forward elements of the Battalion encountered the German blocking line. After the skirmish had ended, Urquhart returned to his Jeep to find that it had been hit by a mortar and his signals operator had been seriously wounded. Lathbury was unhappy with how his Brigade plan was progressing, while Urquhart realized that he was losing control of events and knew that he must get back to his HQ as soon as possible; unfortunately the area was now decidedly unsafe for either man to leave the protection of the 3rd Battalion.

Without being given a choice in the matter Urquhart found himself persistently shadowed by RSM Lord, a six foot two inches ex-Grenadier Guardsman, who had appointed himself as the General's bodyguard. Urquhart did not wish to admit that he needed such attention, but later admitted that the presence of this most excellent of soldiers was always reassuring. However the 3rd Battalion were quite reluctant hosts to the visiting dignitaries. Lt-Colonel Fitch felt uneasy with both his Brigade Commander and the Divisional Commander breathing down his neck as he naturally had to consult them on decisions that he would have normally made himself. This awkwardness was most effectively displayed when, against the wishes of Fitch and his men, Lathbury, with Urquhart's consent, ordered the 3rd Battalion to halt overnight before resuming the advance early the next morning. This was, however, a sensible decision because the Battalion's C Company had been detached by this time, and A Company in the rear of the column were held up in an engagement with German forces. Desirable though an advance was at this time, with the increasing resistance along their route there was little else that could be done other than to wait until the Battalion had properly formed up before pressing on.

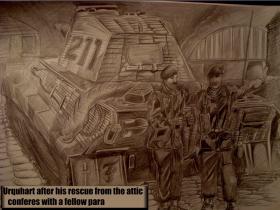

By the following morning both Lathbury and Urquhart were with the leading B Company, which had become separated from the rest of the 3rd Battalion, lingering somewhere in the rear, and spent most of the daylight hours of Monday trapped in a stalemate inside a few houses on the outskirts of Arnhem. By the afternoon it became clear to Roy Urquhart that the situation was getting out of hand and he decided that he must risk returning to Divisional HQ, with only three men accompanying him; Brigadier Lathbury, Captain Willie Taylor, and Lieutenant Jimmy Cleminson. To conceal their escape, Lathbury threw a smoke grenade out of the house in which they had been hiding and the group dashed out of the back door and were in the process of negotiating a fence when Lathbury's Sten gun accidentally discharged and the bullet narrowly missed the General's right foot. Urquhart wrote "I chided him about soldiers who could not keep their Stens under control. It was bad enough for a divisional commander to be jinking about in what was now hardly more than a company action, and it would have been too ironic for words to be laid low by a bullet fired by one of my brigadiers". Beyond the fence a Dutchman appeared carrying a jug of ersatz coffee, which Urquhart regarded as bitter and foul tasting, but they accepted the offer of a drink rather than risk offending him. Arnhem's tight roads and passageways were now infested with German patrols and snipers, but the group pressed on down a street with intersections on the left hand side at every 20 yards; passing the first of these a Spandau opened up on them, and at the second a similar burst wounded Lathbury. The officers dragged him into a nearby house where he had to abandoned, but during their brief stay a German soldier appeared at the window and was killed by Urquhart at point blank range, shot in the face with his pistol. The group pressed on along the Zwarteweg, but it was clear that to proceed in this manner would only result in their capture. Anton Derksen and his family at No.14 offered them shelter in their attic, which Urquhart reluctantly accepted. Almost immediately after the street was filled with soldiers of the Wehrmacht and several surrounded the house in which Urquhart was hiding, and they were followed by a self-propelled gun which came to a halt directly outside, though all were blissfully unaware of the General's presence. All Urquhart could think about was that he had to return to HQ as soon as possible, and he was quite prepared to destroy the SP gun using the few grenades they had at their disposal and then make a dash for it. He was dissuaded from doing so by his companions because they would certainly be killed or captured within moments. Urquhart could do nothing but wait in frustration until British troops caught up with him. In the meantime he became fixated by the exceptionally irritating moustache sitting on Lieutenant Cleminson's upper lip; its hirsute handlebar-like appearance striking him as "damned silly". The Germans learned from British POW's that their General was missing, and so propaganda broadcasts boasted that Urquhart was dead.

It wasn't until morning on Tuesday 19th that the group were able to leave the house. Lt-Colonel David Dobie's attack was in full swing and the area in which Urquhart was hiding was temporarily liberated by men of the 2nd South Staffords and 11th Battalion. He later reflected that it may have been wise for him to have remained on the spot a little longer than he did and take personal command of the four battalions presently trying to crack the German defences in Arnhem, but such had been his frame of mind over the past 30 hours that he and Captain Taylor immediately commandeered a Jeep and set out for Divisional HQ. The area between Arnhem and Oosterbeek was anything but safe and Urquhart drove at full speed in places that were known to be littered with snipers. Bullets whizzed past them on several occasions, but both men and the Jeep survived the journey intact, arriving at the Hartenstein at 07:25. Having seen the futile fighting in Arnhem, Urquhart immediately tried to salvage the situation by ordering the remains of the 1st Para Brigade to break off their attack and create a path for the 4th Para Brigade to charge down, enabling the Division to mount a powerful assault. On his way to see Brigadier Hackett, he abandoned his Jeep to cross the embankment beside the railway line on foot, and as he neared Hackett's camp a German fighter strafed the area and Urquhart effectively rolled into Brigade HQ. Looking through his binoculars at the action going on ahead there did not appear to be much hope that this attack would reap rewards, and so Urquhart ordered Hackett to prepare his Brigade to move south of the railway to resume their attack there.

Returning to the Hartenstein, Urquhart saw a group of panic-struck men led by a young officer shouting "The Germans are coming!", and both he and Lt-Colonel Mackenzie immediately moved to install a sense of discipline. Urquhart wrote: "They were young soldiers whose self-control had momentarily deserted them. I shouted at them, and I had to intervene physically. It is unpleasant to have to restrain soldiers by force and threats, as we now had to do. We ordered them back into the positions they had deserted, and I had a special word with the tall young officer who in his panic had set such a disgraceful example".

With the failure of the attempts to break through to Arnhem and the Division left with nothing to offer in terms of an offensive capability, Major-General Urquhart made the painful, though foregone decision, to abandon John Frost at the bridge and rally what men the Division had left into a defensive pocket near Oosterbeek. His plan was to hold the north bank of the Rhine so that XXX Corps, when they arrived, could secure the southern side and improvise a crossing of tanks into the perimeter, thereby enabling Market Garden to succeed. Urquhart has been criticised, possibly with justification, as to the placement of the pocket defence. It appears that the perimeter simply developed where all the participating units converged rather than in any particular place of strategic advantage. At the extreme south-west of the Oosterbeek Perimeter was the Westerbouwing restaurant, and it has been suggested that this would have been a far better place for Urquhart to place his headquarters rather than at the Hartenstein Hotel. The advantages of it were several. Firstly the area was on high ground and would therefore be of tremendous use to the artillery gunners of the Division's Light Regiment, but also directly to the south were the crossings of the Driel-Heveadorp ferry. The existence of the ferry was overlooked by all echelons of command in the planning stages, and yet had it have been utilised and properly secured it would have been positively invaluable to the survival of the 1st Airborne. Though the RAF reconnaissance photographs clearly highlighted its existence, Urquhart could not recall it being mentioned during the planning phase. The ferry crossing was also the only place in the area where the roads faced each other on opposite banks, and this would have been extremely beneficial to the prospects of XXX Corps putting armour across the river. To have concentrated in this sector would have moved the Division away from the built-up surroundings of Oosterbeek, and to have lost this fine defensive ground may have led to a drastic reduction of their life expectancy. Nevertheless there certainly should have been more manpower allocated to the defence of Westerbouwing. As it happened the area was soon overrun by German troops, and the ferryman sunk his craft to avoid it falling into enemy hands.

Urquhart made a habit of visiting his men as often as possible, though everywhere he went he was received with the same question: "When is the 2nd Army coming?". He had no news to offer them but said that they were expected to arrive at any time. When it was heard that the Guards Armoured Division was about to take Nijmegen bridge, the relieved General gave the order that this news be passed on to every man in the Division. On one of his trips he visited the Independent Company in a Jeep with his aide-de-camp, Captain Graham Roberts, but arrived during a fierce gun battle and found himself driving in No Man's Land. Heads emerged from nearby slit trenches and beckoned them over, Urquhart braked sharply and the two men sought refuge in a trench. Asking Roberts to try and rescue the vehicle, Urquhart made a dash to Major Wilson's HQ, situated 50 yards away. Roberts got in the Jeep raced away, but he drew enemy fire and the Jeep was wrecked moments after, throwing Roberts clear and leaving him with a few wounds.

On Thursday, Charles Mackenzie informed Urquhart that the German prisoners being held in the tennis courts near the Hartenstein Hotel, numbering approximately 200, were complaining about their treatment and had begun to quote the Geneva Convention. The two men went to see them with an interpreter in tow. Urquhart observed: "As they lined up, I saw that they had been pretty badly shaken. Around the tennis courts stood the Military Police and glider pilots with Stens under their arms; the prisoners, in shabby uniforms and with weary, bearded faces, stood in sullen silence on the pitted courts where already a number of mortar bombs had burst. They were hardly in worse case than my own men who were being blasted by tree bursts which scattered metal fragments far more widely than a ground hit. Glancing up and down the lines, I said: 'We expect you to behave in the way that British soldiers have to behave in conditions such as this. We will do everything possible to enable you to dig in. As for food, I know how you are feeling. But we have none ourselves, and you will get what is due to you as it becomes available.' I knew that once it is suggested to a German that he is not as good as someone else, he damn soon tries hard to prove that he is. When I left, the prisoners were being issued with several shovels to dig through the hard surface of the courts. Others used mess tins to scoop away the gravel and soil."

Due to the communications failure, Divisional HQ were having a hard time in conveying the seriousness of their plight to the outside world. On Thursday night Urquhart sent a message to Lt-General Browning's Corps HQ at Nijmegen, reading: "No knowledge elements of Div in Arnhem for 24 hours. Balance of Div in very tight perimeter. Heavy mortaring and machine-gun fire followed by local attacks. Main nuisance SP guns. Our casualties heavy. Resources stretched to utmost. Relief within 24 hours vital." On the following day he asked his Chief of Staff, Charles Mackenzie, and his senior engineer, Lt-Colonel Eddie Myers, to cross the Rhine, locate either Browning or Horrocks, and give them an unequivocal picture of what was happening. He told them: "It's necessary that they should know that the division no longer exists as such and that we are now merely a collection of individuals holding on. Do try and make them realize over there what a fix we're in." A further message was broadcast to Corps HQ on the evening of Saturday 23rd, which Urquhart was very careful about phrasing for fear of conveying even the slightest notion that they wanted to withdraw, so much so that as they reported to Divisional HQ throughout the day, he asked Brigadiers Hicks and Hackett and Lt-Colonel Robert Loder-Symonds for their thoughts, but they had no objections. The message read: "Many attacks during day by small parties inf, SP guns and tanks including flamethrowers. Each attack accompanied by very heavy mortaring and shelling within Div perimeter. After many alarms and excursions the latter remains substantially unchanged. Although very thinly held. Physical contact not yet made with those on south bank of river. Resup a flop, small quantities amn only gathered in. Still no food and all ranks extremely dirty owing to shortage of water. Morale still adequate, but continued heavy mortaring and shelling is having obvious effects. We shall hold but at the same time hope for a brighter 24 hours ahead."

On Sunday 24th, radio contact was made with Major-General Ivor Thomas of the 43rd Wessex Division. "I tried to convey to him the critical state in which the Division now found itself. 'We are being very heavily shelled and mortared now from areas very close to our positions' I explained. To my intense annoyance, Thomas replied with some impatience: 'Well, why don't you counter-mortar them? Or shell them?' Imagining the cosier environment from which he was speaking, I flared up. 'How the hell can we?' I retorted. 'We're in holes in the ground. We can't see more than a few yards. And we haven't the ammunition.' I found his gratuitous advice infuriating. This was just like Thomas, who sometimes could make me very angry. Having worked with him before, however, I knew that he would do what he could to help us. I suppose I was getting on edge and touchy. I was also sure that he had not got the situation clear at all."

On Monday 25th, Urquhart was told to withdraw his men from Oosterbeek at a time of his choosing. At 8am he radioed Major-General Thomas and said "Operation Berlin", the codename for the withdrawal, "must be tonight". It was not an easy thing to do as his Division was extremely weak at this time, and if the Germans sensed that a withdraw was in progress then they would rush in to cut them off from the River bank. His plan was excellent under the circumstances. Calling Charles Mackenzie, his Chief of Staff, to work out the finer details, he said: "You know how they did it at Gallipoli, Charles? Well, we've got to do something like that". Many years ago, Urquhart had studied the classic withdrawal from this First World War conflict in extensive detail for a promotion examination. He remembered how great care was taken to maintain the illusion of defiance until the last moment, meanwhile the forward positions were thinned out and the force was evacuated from the beaches in good order, whilst the enemy were completely oblivious to it. The Division would withdraw from top to bottom, with those in the north leaving their positions first, and so on until everyone was out. There were so many wounded by this time that it was agreed that they could not be evacuated and so would stay behind, together with all medical staff, and take over the vacated positions, meanwhile the Light Regiment and XXX Corps would continue to fire their guns until the last moment. This way it appeared as if nothing had changed. When the senior officers assembled at Divisional HQ to hear the plan, Urquhart gave specific instructions that word of the withdrawal should not be given until it was almost time to depart, as with a day's fighting to still to endure the capture and subsequent interrogation of anyone who knew would place the entire operation in jeopardy.

As the time to take their place in the line drew near and those at Divisional HQ set about burning all their papers, Urquhart found the bottle of whisky that he had brought in his pack and promptly forgot about, and so he passed it around for everyone to have a sip. He visited the wounded in the cellars to say goodbye to those who were conscious and aware, and then HQ departed in single file, following the lengths of parachute tape down to the riverbank. Though only a short distance, the journey took an unusually long time as close by German voices and volleys of mortar and small arms fire forced a halt from time to time. All were waiting quietly and patiently for their turn to be ferried across. A few mortar bombs landed on the embarkation area and everyone went to ground, and after what seemed like hours despite the time being only close to midnight, Urquhart's group was loaded into a boat. Packed almost to the point of sinking, the boat became stuck in the mud as it tried to set off, but Hancock, Urquhart's faithful batman, climbed out and pushed them clear. Half way across the boat's engine failed and it took several minutes of drifting in the strong current before it could be persuaded to restart, meanwhile German machine-gunners were firing across the river from the high ground at Westerbouwing, but they made it safely across.

Urquhart and his ADC, Captain Graham Roberts, went straight to Major-General Thomas's Headquarters to announce his arrival and to request transport so that he could report to Lt-General Browning as soon as possible. He was invited indoors while he waited for a Jeep, however he declined and chose to stand outside in the rain. Urquhart was furious with Thomas for his complete lack of urgency in the crucial stages. During the night he was transported to Corps HQ in Nijmegen, but before meeting with his Commander, Urquhart, very wet and too tired to even sit down, was offered the opportunity to change into fresh clothes, but he refused, later admitting that he perversely wanted Browning to see him as he was. Browning took his time in coming, but when he did arrive Urquhart noted: "He was as usual immaculately turned out. He looked as if he had just come off parade instead of from his bed in the middle of a battle. I tried to display some briskness as I reported: 'The division is nearly out now. I'm sorry we haven't been able to do what we set out to do.' Browning offered me a drink and assured me that everything was being done for the division. 'You did all you could,' he said. 'Now you had better get some rest.' It was a totally inadequate meeting, but my mind had already seized up and every thought required an effort of willpower." Throughout the battle Urquhart had desperately wanted to sleep, but once it was all over he found that there were too many thoughts running through his head to allow rest. He was heavily burdened by the fact that of the 10,000 men he was responsible for, only 2,000 had returned across the Rhine. This had been his first divisional command and he had become very attached to it, with its "wonderful spirit", but over the previous nine days he had seen it ripped apart before his eyes.

On the following day, Wednesday 27 September, he visited the commanders of those local units who had aided the Division during the battle, giving special thanks to the gunners of the 64th Medium Regiment, who had done so much to ensure the 1st Airborne's survival. He believed that their shooting prowess had been such that they had earned the right to wear the Pegasus arm badge of the Airborne Forces and he later made determined efforts to sanction this, but the War Office were not inclined. Returning to Corps HQ, Urquhart began to dictate letters of thanks to all those units who had supported the Division, a task which he could normally accomplish with ease, but his mind had so come to a standstill that he had difficulty in forming even the simplest of comments. Eventually Browning's secretary offered to write the letters on his behalf, and as such they were rather formal and didn't convey the deep feelings of gratitude that he would have preferred. A meal was held that night for the senior officers with Browning and Horrocks in attendance, but Urquhart had yet to recover his appetite after nine days of deprivation and the battle still weighed heavy on his mind, and so he was glad when the party had come to an end.

On Thursday 28 September, he lunched with General Miles Dempsey at his 2nd British Army HQ, and in the evening visited Field Marshal Montgomery near Eindhoven. They discussed the battle before retiring, and Monty offered Urquhart the use of his personal aircraft to take him back to England, however Urquhart declined as he had earlier received a similar proposal from Major-General Williams, the air commander of Market Garden, and considering their earlier dispute over the placement of the drop zones he felt it would be tactful to accept the offer. Taken back to England the next day, Friday 29th September, he was received by Lt-General Brereton, commander of the 1st Allied Airborne Army, and from there was summoned to meet King George VI, Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands, the War Office and the CIGS, and he also attended a "frighteningly large" press conference. Concluding his official report of the battle in January 1945, Urquhart wrote: "The operation was not one hundred per cent successful and did not end quite as we intended. The losses were heavy but all ranks appreciate that the risks involved were reasonable. There is no doubt that all would willingly undertake another operation under similar conditions in the future. We have no regrets."

Major-General Urquhart was awarded the Dutch Bronze Lion for his handling of the Division throughout the battle. His citation reads:

General Urquhart landed on 17th September 1944 in command of 1st British Airborne Division with the task of capturing the bridge over the Neder Rijn at Arnhem, in Holland. During the ensuing eight days battle for the capture of the Arnhem road bridge this officer displayed outstanding qualities of leadership and courage. During the phase of the battle when 1st Parachute Brigade became separated from the rest of the Division this officer personally organised an operation for the relief of 1st Parachute Brigade and himself became involved in street fighting during this period. Later, when the remnants of the Division were withdrawn into a close perimeter, his conduct of the defence, and his unequalled cheerfulness and determination were largely instrumental in ensuring the magnificent defence put up by the troops of his Division. During the withdrawal his cool planning, foresight and initiative were entirely responsible for 2,000 men of the Division rejoining their comrades of the Second Army on the southern bank of the Neder Rijn. The conduct of this officer throughout this most trying period was beyond praise.

Roy Urquhart's name became famous as a result of Arnhem, and for his actions there he was made a Companion of the Order of the Bath and later received the Dutch Bronze Lion. Field Marshall Montgomery also recommended his name to CIGS in the event of Lt-General Browning being promoted and leaving a vacancy as Deputy Commander of 1st Allied Airborne Army. Immediately after the end of the war, Urquhart took Divisional HQ and the 1st Airlanding Brigade to Norway to oversee the German surrender, and he was rewarded with the Norwegian Order of St Olaf.

In 1947 he was charged with the raising of the 16th Airborne Division of the Territorial Army. Urquhart's military career was tainted with the Arnhem defeat, and he remained at the rank of Major-General until he retired from the Army in 1955. From then until his retirement in 1970, he pursued a career in heavy engineering, being the Director of Davy and United Engineering Co. Ltd.

In 1958 Urquhart published his excellent book, Arnhem, describing the battle from his perspective, and he presided over the 30th and 35th anniversaries of the Battle in 1974 and 1979.

Urquhart was portrayed by Sean Connery in the 1977 film A Bridge Too Far, for which he himself served as Military Consultant.

He died on 13 December 1988 at Port of Menteith, Perthshire, aged 87 years, leaving a wife and four children.

Military career.

2nd Lt. 24.12.1920

Lt. 24.12.1922

Capt. 26.03.1929

Maj. 01.08.1938

A/Lt-Col. 28.12.1940 – 27.03.1941

T/Lt-Col. 28.03.1941 – 18.11.1943

WS/Lt-Col. 19.11.1943

A/Col. 19.05.1943 – 18.11.1943

T/Col. 19.11.1943 – 09.01.1945

WS/Col. 10.01.1945

A/Brig. 19.05.1943 – 18.11.1943

T/Brig. 19.11.1943 – 09.01.1945

A/Maj-Gen. 10.01.1944 – 09.01.1945

T/Maj-Gen. 10.01.1945

Maj-Gen. 17.11.1947, seniority 20.01.1946 (ret’d 20.12.1955)

24.12.1920. Commissioned into the Highland Light Infantry (1st Battalion(1921-1925).

Depot (1925-1927). 1st Battalion (1927-1933))

01.05.1920 – 20.01.1936.

Adjutant, 1st Battalion The Highland Light Infantry.

Jan 1936 – Dec 1937. Staff College, Camberley (psc)

Mar 1938 – Oct 1938. 2nd Battalion The Highland Light Infantry.

16.10.1938 – 14.05.1939. Staff Captain, India.

15.05.1939 – 15.10.1940. Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General, Army HQ, India.

16.10.1940 – 27.12.1940. Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General, 3rd Infantry Division.

28.12.1940 - 27.03.1941 Assistant Adjutant & Quartermaster-General, 3rd Infantry Division.

28.03.1941 – Mar 1942 Commanding Officer, 2nd Battalion The Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry

April 1942 – 18.05.1943 General Staff Officer 1st Grade, 51st (Highland) Infantry Division, (North Africa)

19.05 – 30.09.1943 Commander, 231st (Malta) Infantry Brigade, (Egypt, Sicily – Italy)

01.10.1943 – 09.12.1943 Brigadier General Staff, XII Corps

10.12.1943 – 31.08.1945 General Officer Commanding, 1st Airborne Division, (UK, North-West Europe, Arnhem – Norway, UK. [from 21.5 – 24.8.1945 designated: HQ Norway Command]

01.11.1945 – Dec 1946 Director of Territorial Army & Army Cadet Force, War Office

07.01.1947 – 09.12.1948 General Officer Commanding, 16th Airborne Division (T.A.)

20.12.1948 – Feb 1950 General Officer Commanding, Lowland District

Mar – Aug 1950 General Officer Commanding, Malaya District, Malaya & General Officer Commanding 17th Ghurka Division (Malaya)

Aug 1950 – Jun 1952 General Officer Commanding Malaya

23.07.1952 – 20.12.1955 General Officer Commanding-In-Chief, British Troops in Austria

1955 Retired

Colonel, Highland Light Infantry, 1954-58.

Publications consulted; ARNHEM by Major-General. R.E. Urquhart, CB, DSO. 1958. The Sky Generals by Major Victor Dover.1981. URQUHART of Arnhem by John Baynes. 1993.

Researched and compiled by Bob Hilton.

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.