George Frederick Hopkinson was born on 14 December 1895, the son of George Hopkinson and Ada Hopkinson of Retford, Nottinghamshire. He was Killed In Action 12 September 1943, aged 47 and now lies at rest in Bari War Cemetery, plot X, row B, grave 33.

Prior to the start of the First World War, Hopkinson worked as an apprentice at an engineering works at Retford, Nottinghamshire. Too young to join up when the conflict began, he enlisted in the British Army in early 1915, joining the Officers Training Corps and then being commissioned into the 4th Battalion, The North Staffordshire Regiment as a Second Lieutenant (on probation) on 27 March 1915. After a short period on Guernsey with them, Hopkinson was posted to France as a signal officer in the 72nd Infantry Brigade. On 16 September 1918 he was awarded the Military Cross for his actions during the retreat of the British Army in 1918; the citation read:

Lt. George Frederick Hopkinson, North Staffordshire Regiment, Special Reserve.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. During a fortnight's operations of a most arduous description, his services in maintaining communication between brigade headquarters and the front line were most valuable, and his example of fine personal courage and coolness under heavy fire, worthy of the highest praise. On one occasion, having been unable to find the battalion to whom he was to convey orders for retirement, he returned a second time, but encountered an enemy patrol, who opened a heavy fire. Eluding the patrol, he came across one of our wounded, whom he helped to get on to his motor-cycle and managed to convey back to safety, though all the time being subjected to heavy fire.

Lieutenant Hopkinson’s nickname, ‘Hoppy’, probably had its derivation in the abbreviation of his name, but also, no doubt, because he was short, light of foot and walked as though he had springs in his heels.

Hopkinson left the army shortly after the end of the conflict, and in 1919 enrolled in Caius College, Cambridge, where he studied for a civil engineering degree. He was somewhat older than most of the other undergraduates, but that did not deter him from throwing all his enthusiasm into college activities. He enjoyed riding and in this sport he made up for his lack of weight and height with tremendous vigour and a seemingly endless source of energy. He had a great sense of fun and distinguished himself more than once by organizing practical jokes.

The most famous of these, in those post-Great War years, was a ‘Rag’. He decided that it would be a good idea to capture the Jesus College gun. It necessitated planning a delicate operation which was carried out with great precision. A detailed ‘operation order’ was issued, including the action to be taken against any hostile or other interference. ‘Hoppy’ also organised, with equal efficiency and panache, the kidnapping of the ‘Thineas’ – a mascot of the University College Hospital which was displayed at important football fixtures. His ventures were always highly successful, including his personal ‘cover-up’ plans. When not engaged in all too frequent pursuits of this kind he achieved his civil engineering degree. Here was a character smaller than most in body, but a great deal larger in spirit.

When he had finished his studies, he spent much of the early 1920s travelling throughout Europe, visiting Poland, the Baltic States and Russia.

However after this period of travelling, in 1923 he returned to the Army and the North Staffordshire Regiment, and by the following year had reached the rank of Captain and this inspired him to study for entry to the Staff College. Although his nature was full of fun he took his military proficiency very seriously and was known to study into the early hours of the morning until he found it necessary to stand up in order to stay awake!

It was difficult for Captain ‘Hoppy’ to satisfy his abundant vigour, so he took up hunting and rode with the South Stafford pack and joined the Regimental pack of Bassetts. In 1925, he was appointed Adjutant and a report recorded that he possessed ‘a balanced mixture of discipline, loyalty, efficiency and good humour’.

He founded ‘The Bachelors Club’ in the Regiment, the purpose of which was to slow down, if not halt, the wave of matrimony which seemed to be overwhelming his brother officers. If an officer succumbed to an engagement he was required to give a dinner party for all the other members of the Club who had not fallen into the trap. This was an expensive penalty, but when a wedding eventually took place a silver ashtray was presented to the victim as a memento of his bachelor days and of his resignation from freedom and the Club. It is perhaps, not surprising to record that several very good dinners took place. ‘Hoppy’ pursued the purpose of the Club while he was at Staff College; as a bachelor he made bets with his brother officers that he would outlast them. At five pounds a time he claimed that he drew a steady income.

In 1927, his Regiment moved to Blackdown, at which time he had a great urge to indulge himself in cross-country running. He was now thirty years of age and on one occasion he led the Regimental team to second place in the Army cross-country championship, losing the title by two points to the Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry. He blamed the defeat by such a narrow margin on the shortness of his legs!

In January 1930, ‘Hoppy’ had gained entry to the Staff College, Camberley, and was an entusiastic student. When he passed out of the Staff College he was seconded from his regiment and appointed as a General Staff Officer (GSO III) to the War Office, and was promoted a short time later to GSO II at the School of Artillery at Larkhill; during the period, he also learnt to fly, gaining his pilot's license in 1933.

In 1936 he returned to his regiment and commanded a rifle company as a brevet major, but in 1937 he once again retired from the Army. It will not have passed unnoticed that ‘Hoppy’ also had a habit of hopping in and out of the Army. He was given an appointment with Brasset and Company, who were civil engineers concerned with the construction of a steelworks in Turkey. Hoppy’s job was not confined to engineering: he was also engaged in promoting good relations between Great Britain and Turkey, as this country was then regarded as a potential ally.

When the Second World War began in September 1939, Hopkinson immediately rejoined the Army and was posted to the Staff of the Military Representative that served on the Supreme War Council. In November 1939 he took command of a General Headquarters Reconnaissance Unit which served throughout the Battle of France; injured during a motorcycle accident, he recovered in time to evacuate himself and many of his unit's vehicles from Dunkirk. He was appointed Officer of the Order of the British Empire on 20 August 1940 for his work during the Battle of France, in particular as liaison officer to Belgian forces.

‘Hoppy’ was one of the first volunteers for the then fledgling airborne forces in Britain in 1940. He qualified as a parachutist, injuring his back on his first jump; on his second, still wearing a plaster cast, he landed in Poole harbour! Here was an indefatigable and restless officer. He flew as a passenger in RAF bombing raids over Germany. He did this, he said, ‘to relieve the tedium of training and the frustration of waiting to be committed to battle, and above all to get as much experience of active operations as possible’. He could not resist the urge to become involved in everything – he volunteered to take part in one of the first glider snatch-off experiments which in the early days was a hazardous business.

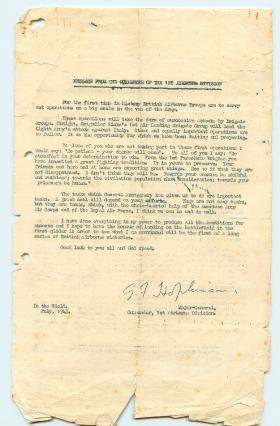

By April 1943 Hopkinson had been promoted to the rank of Major General, and assumed command of 1st Airborne Division; informed that Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily would take place in several months, Hopkinson was determined that the division would participate, and thus implemented a tough training regime to ensure that the division was sufficiently prepared.

To get his command involved in the forthcoming operations in ‘Hoppy’ made a personal approach to General Montgomery, bypassing General Browning who was the Airborne Adviser at 15th Army Group Headquarters. He convinced Montgomery of the advantage of using the airborne arm in Sicily. However, Montgomery had no experience of airborne operations and General Hopkinson’s knowledge was limited to airborne training. When Lieutenant-Colonel George Chatterton, the Commander of the British glider pilots, pointed out that only partially trained crews would be flying unfamiliar American gliders in a mass landing in total darkness, he was overruled by ‘Hoppy’.

Operation ‘Husky’ began on the night of 9 July with an airborne assault by 1st Airlanding Brigade and the 1st Parachute Brigade on the 13 July. The 1st (British) Airborne Division, and elements of the American 82nd Airborne Division suffered heavy losses in men and equipment as they carried out their objectives.

Due to a number of factors, including poor navigation and the inexperience of the pilots of the transport aircraft, many of the gliders transporting 1st Airlanding Brigade failed to reach their assigned landing zones. One such glider, flown by Major John Place, carried Major General Hopkinson and members of his staff; the tow-rope of the glider was detached prematurely and it was forced to ditch in the ocean. Although uninjured, Hopkinson was forced to wait by the partially-submerged glider until daylight, when he was picked up a Royal Navy destroyer. It was a coincidence that the skipper of the destroyer which dragged him from the sea was an old friend of Hoppy’s and had rowed with him in the same boat while they were at Cambridge. After the battle, ‘Hoppy’ wrote to a friend, “I was late for the battle having landed in the sea, but they got on without me for the first few hours”.

After both brigades had accomplished their missions they were withdrawn to North Africa to recover, and Allied ground forces began to fight through Sicily; fighting ended on 17 August, and in early September the Allies launched their invasion of Italy itself.

On 8 September 2nd Parachute Brigade and 4th Parachute Brigade landed in Italy, followed several days later by the remainder of the division landing at the port of Taranto. Hopkinson landed with the rest of the division and accepted the surrender of the Italian garrison there, then ordered the division to advance northwards. Fighting was fierce against a strong German rearguard, which set up a number of ambushes and roadblocks to deter the division; one such roadblock was set up near the town of Castellaneta and defended by a unit of Fallschirmjaeger. On 11 September, 10th Parachute Battalion assaulted the roadblock, with Hopkinson in close attendance; during the fighting, Hopkinson was hit by a burst of machine gun fire and died of his wounds the next day.

One of his battalion commanders said of him, “’Hoppy’ was very much a front-line general, and any brigade or battalion in trouble would very soon find him in its midst”. He was a restless, endearing character, as can be gauged, with many other things, by his frequent appearances as best man and godfather.

Lieutenant-Colonel Vladimir Peniakoff, DSO, MC, of Popski’s Private Army fame, said of ‘Hoppy’: “It might seem a pity that he was killed, not on one of the airborne operations for which he had prepared himself and his men with great fervour, but on a humdrum inspection of his forward troops; but it is a fit end for a soldier to lose his life in the punctilious performance of his less spectacular duties”.

‘Hoppy’ had given his red beret to Montgomery, who later presented it to the Airborne Forces Museum in Aldershot at the time of its official opening on 23rd March 1969.

His epitaph is in every line of Wordsworth’s poem:

Who is the happy Warrior? Who is he

That every man in arms would wish to be?

Major-General Hopkinson was replaced by Brigadier Eric Down, commander of 2nd Parachute Brigade. He was the only British airborne general to be killed during the conflict.

1940. Commanding Officer GHQ Regiment.

1941. Commanding Officer 31st Independent Brigade Group.

1941 – 1943. Commanding Officer 1st Airlanding Brigade Group.

1943. Commanding Officer 1st Airlanding Brigade.

1943. General Officer Commanding 1st Airborne Division, North Africa, Sicily & Italy.

Publications consulted;

PHANTOM by Philip Warner.

The Sky Generals by Major Victor Dover

Compiled by B Hilton, from original work by Adam Martin: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_F._Hopkinson

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.