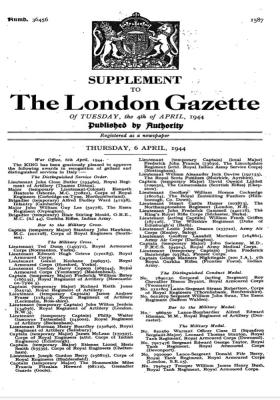

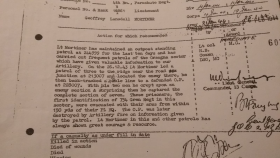

As a Lieutenant, Geoffrey Mortimer volunteered for the Airborne Forces in 1942, and after the selection process at Hardwick Hall he attended Parachute Course No.10 at RAF Ringway, from the 16 to the 27 March 1942. This was the main parachute course for the formation of the 4th Parachute Battalion, and consisted of nine other officers and 146 other ranks. He served with the Battalion in Italy, Southern France and Greece. For his actions in Italy he was awarded the Military Cross in 1944, and was Mentioned in Despatches in 1945. His citation for the Military Cross reads:

Lieutenant Mortimer has maintained an outpost standing patrol at 244999 for the last ten days and has carried out frequent patrols of the Orsogna sector which have given valuable information to our Artillery. On the 26th December 1943 Lieutenant Mortimer led a patrol of three to the ridge near the road junction at 213007 and located the enemy there, he then back-tracked a cable line to a defended Observation Post at 228007. With his two men he crept upon an enemy section and surprising them he captured the complete section of seven. These prisoners, the first identification of 754 Grenadier Regiment in this sector, were evacuated with their arms from within 150 yards of their Platoon Headquarters. The Observation Post was later destroyed by Artillery fire on information given by the patrol. Lieutenant Mortimer in this and other patrols has always shown great courage and resource.

On the 15 August 1944, as Second-in-Command of "C" Company, he took part in the invasion of Southern France and was the first man to jump from aircraft chalk number 121, landing accurately on DZ-O. The following is his account of Operation Dragoon:

Before we flew off from Rome I had a friendly word with the U.S. pilot (Capt Clark) of the Dakota to reassure myself that his seventeen passengers were going to be dropped at the right place. From the inside breast pocket of his leather, fur-collared jacket he produced what had been a blank post card on which had been stenciled an outline map of the whole Mediterranean, from Gibraltar to Palestine, with Italy the size of a swan matchstick and Sardinia and Corsica the size of a typewriter exclamation mark and dot respectively. There was a dotted line leading from the middle of the matchstick (Rome) through the north coast of Corsica and on towards the 'soft underbelly' of Europe. He said 'I reckon we fly right along that dotted line'. I then told him that our detailed briefing from air photographs was that we should jump out 8½ minutes after crossing the coastline near Saint Raphael and that the road from there inland to Le Muy should show up as a silver ribbon in the bright moonlight which the weather forecast had predicted. Having regard to his flying speed it would take just so many minutes to get there after crossing the coastline which would also show up in the bright moonlight (around 3.30 a.m.). Captain Clark's response was 'Geeze, what do you know about that!' He was very sincere and friendly and I don't think he was pulling my leg. However, we were dropped quite near to the pre-appointed Dropping Zone but I had the misfortune to land in a tree, having got my bearings on the way down by observing the onward flight of the Dakota and the silver ribbon of the road below me in the moonlight.

By approximately 5 am., many, but by no means all, of 'C' Company of the 4th Parachute Battalion started to assemble at their RV, having been attracted there by clouds of pink smoke bellowing from the chimney of a house called Le Gautier at a crossroads some short distance from the town of Le Muy. Our immediate objective was a large villa set in an extensive garden surrounded by a high stone wall and defended by some 40-50 German infantry. After lobbing a few 3" mortar bombs into the garden we made a frontal attack, scaling the 10ft high wall and were among the Germans in a hand to hand skirmish. We suffered about nine dead, - the Germans about 15 I believe. The remainder were marched off as prisoners.

Next day, in the early afternoon, a Frenchman, Monsieur André Blanchard, wearing a white shirt, came to tell us that a large number of Germans wanted to surrender but that they would only do so if a British officer would lead and guarantee their safe transfer. This, as a captain and german speaker I was only too pleased to do, having discussed the matter with Jim Gourlay, the company commander. (I was his 2nd i/c).

So off we set, myself, my batman Tom Carson and the white-shirted Frenchman. Having gone about 100 yards towards Le Muy we were taken prisoners and escorted into the town school playground where Germans in a long trench dug immediately behind a low perimeter wall were firing in the direction of Americans who were approaching house by house through the town. I then complained that we had come in good faith to negotiate and I demanded to speak to their commander, a German colonel whose H.Q. and staff were in the school building. I was admitted. The colonel and his RSM listened to what I had to say and, just at that time, we could see through his window hundreds of white parachutes floating down some two miles away. The colonel then told me that he would hold a conference with his soldiers and that I was to wait in the corridor outside the room. Whilst waiting, a German corporal came up to me, nudging me on the shoulder and saying 'Anyway, we beat you at football in the 1936 World Cup.' I then went outside to join Tom Carson and the Frenchman who were standing side by side in the trench with the Germans who, in turn, were firing at the Americans. The Frenchman took off his white shirt, grabbed the rifle out of the hands of the nearest German and hoisted his improvised white flag into the air. The German grabbed it back again, saying 'No, no, it's not over yet' and so began a tug of war between Msr. Blanchard and the German. I was then called back into the school building where the colonel told me that they had decided not to surrender. So, after a deathly silence, I asked him 'What about us?' Haughtily he announced 'You?, you can go back to your lines. You are only a captain and I am a colonel. You ought to have negotiated first over the wireless.' So I said 'Fair enough, but we need an escort, otherwise we'll be shot at on our way back, as soon as your men see a British uniform.' The colonel said 'Du hast recht' and provided us with an escort of two German soldiers who led us to the outskirts of the town and then said 'this is as far as we can go.' and promptly left.

At that moment several Germans came running out of a farm yard, saying 'Was hat er gesagt?' It turned out that these, some forty of them, were the ones who had told the Frenchman that they wanted to surrender. When I told them that their colonel had refused my invitation and that they were to fight on, they cursed with some foul german swear words. Then they said that if we attacked their farm yard at midnight they would immediately surrender, provided I assured them that we would be firing into the air. So on we three went back towards our lines. I advised that we should saunter, kick the occasional stone, give the impression that we were out for a peaceful country stroll and definitely, but definitely, not run. Unfortunately my french can't have been too good because Msr. Blanchard started to run when we were only some hundred yards away from base. We were followed by a hail of bullets so we then all ran, jumped over a wall, went through an orchard and got back to our lines.

Some two hours later, a column of Germans escorted by Americans came marching down the road, headed by the colonel in an american jeep, which I ordered to stop. The german colonel explained that he hadn't surrendered but that his men had and that he himself had been taken prisoner. One of the G.I.s in the jeep said to me 'You must have been that crazy Brit we saw among these krauts shooting at us from the school playground, can you beat that!' So I waived them on.

I don't know whether Monsieur André Blanchard is still alive. He did give me his address. It was 'Domaine St. Romane, La Motte.

ANNENDUM.

Since recording this experience I have discovered that the Americans who captured Le Muy on the 16th of August 1944 belonged to the 550 Glider Borne Battalion Group which landed South of Le Muy at 6:20 pm on D day, the 15th. They put in an unsuccessful attack on that village the same night and withdrew until the following morning when they tried again and, by 3:30 pm on D+1, the village was completely captured and all resistance had ceased, - 170 prisoners were taken.

These were the Americans who had been exchanging fire with the Germans entrenched in the school playground, side by side with whom Msr Blanchard and Tom Carson had been standing in a tug of war with a German.

The 170 prisoners were, of course, the long column of escorted Germans, preceded by their Colonel in a jeep which I ordered to stop so that I could ask him why he had changed his mind.

I firmly believe that by talking to them between 1 and 2pm that afternoon, both in the school and in the farm yard, they were persuaded that their position, surrounded as it was by British and American troops, was untenable and that I had helped in some small way to save further loss of blood on both sides. We, C Company of the 4th Bn., and the Germans had already lost quite a lot the previous day.

Created with information kindly researched and supplied by R Hilton and SA Evans.

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.