Charles Baillie Mackenzie was born on the 29th December 1909 in Scotland, the son of Theodore Charles Mackenzie. He was educated at the Royal Military College and Joint Services Staff College, and was commissioned, as a Second Lieutenant, into The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders on the 30th January 1930. He was promoted to full Lieutenant exactly three years later and in May 1933 he was employed with the King’s African Rifles, until April 1935.

He was promoted to Captain on the 1st August 1938 and on the 1st June 1940 he took up the post of a General Staff Officer 3rd Grade (G.S.O. III) at 1st Army Headquarters, this lasted only a week before he was posted to a Corps Headquarters. He was only there for three months before he was posted again, this time as a Brigade Major, upon promotion to Acting Major. In October 1941 he took up his post as a General Staff Officer 2nd Grade (G.S.O. II) at General Headquarters H.F.

On the 17th December 1942 he took over command of the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion and prepared it for active service overseas. He attended parachute course No 45, at R.A.F. Ringway, 4th – 13th January 1943, and successfully completed the ‘Long’ course of seven descents. In May 1943 the Battalion, along with other elements of the 1st Airborne Division sailed for North Africa, where they prepared for airborne operations in Sicily. Before they could take part in the operation to drop near Augusta, the ground forces had over-run it, and it was cancelled.

The opportunity for action came on the 9th September 1943, when the 5th (Scottish) Parachute Battalion landed at the Italian port of Taranto, as part of Operation ‘Slapstick’. Lt-Col. Charles Mackenzie led the battalion through the campaign in Southern Italy until the 22nd November 1943, when he was posted back to England. Here he took up the post of a General Staff Officer Grade I (G.S.O. I) at 21st Army Group Headquarters.

It was on the 20th August 1944 that he took up his post as the G.S.O. I at 1st Airborne Division Headquarters, then based at Fulbeck Hall in Lincolnshire, but spending most his time at the 1st Airborne Corps Headquarters at Moor Park.

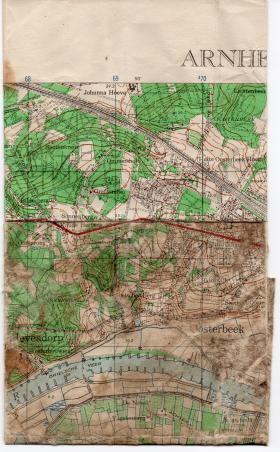

He was described by Major General ‘Roy’ Urquhart, the G.O.C. 1st Airborne Division, as “a slightly built Scot with an air about him of immense responsibility”. After Operation ‘Comet’ was cancelled on Sunday 10th September, he accompanied other officers of the Divisional staff on a boating expedition to the River Thames, but the party were soon recalled to base when the outline of Market Garden was announced later on that same day, and Mackenzie immediately entered discussions with the air staff. With most of the plan settled Mackenzie, bearing bad news, visited Urquhart at Airborne Corps HQ, at Moor Park Golf Club, on Friday 15th September where his commander was taking the opportunity to enjoy a round on the few holes still playable. Unwilling to distract the General from his putting, he waited patiently on the edge of the green, but Urquhart urged him to relate what was troubling him. Mackenzie announced that they were to be given fewer gliders on the First Lift, for which no explanation was offered but these were the gliders removed from the 1st Airborne Division to transport Lt-General F.A.M. Browning’s Corps Headquarters to Nijmegen. Urquhart insisted, and Mackenzie agreed, that whatever was to be lost from their load that it should not include anti-tank guns. Neither were willing to place their faith in the Intelligence reports that stated there would be little or no enemy armour in their sector.

On the edge of LZ-Z was the village of Wolfheze, neighbouring which was a mental asylum whose grounds were almost as large as the village itself. Mackenzie had discussed the asylum with Urquhart and they concluded that it was entirely possible that it could house enemy troops, and with it situated on the edge of the drop zone it was too significant a threat to overlook and so on the morning that Operation ‘Market-Garden’ was launched it was to be bombed by American aircraft. A few hours before the airborne armada took to the skies, Mackenzie received a telephone call from a senior officer of the U.S.A.A.F. who wanted categorical assurances that the asylum contained soldiers and not mental patients. Mackenzie accepted responsibility, to which the American said, “On your own head be it”. It transpired that the asylum did contain mental patients, and the bombing left 45 dead, 35 dying, and many more wounded. 60 mental patients, mostly women, had run terrified into the woods and were to be amongst the first Dutch civilians to encounter the Airborne troops when they arrived.

Before boarding his allotted glider, Mackenzie was informed by Urquhart that in the event of his death or capture, command of the Division should first pass to Brigadier Lathbury, then to Hicks, and finally to Hackett. The possibility of such dire circumstances arising where command should pass beyond Lathbury was considered most unlikely, but Mackenzie agreed. However, when it had been discovered after landing that radio communications throughout the Division were almost non-existent, Urquhart left Mackenzie in charge of Divisional HQ and set out by jeep to find Lathbury. Nothing was heard of either of the two men for the following 36 hours. In the evening a few randomly aimed mortar bombs fell down amongst the Divisional staff, and so Mackenzie decided to move his men out onto one of the landing zones, where they spent the night operating from within a number of abandoned gliders, but before dawn they had established themselves in a few houses on the Heelsum Road.

By this stage it was clear that all was not well. Of the little Mackenzie knew, he had heard that at least part of the 2nd Parachute Battalion was at Arnhem Bridge, but the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions were some distance away from it and were having to fight through increasingly heavy opposition. His General was missing, as was his deputy, and though he had made a few minor decisions during the night Mackenzie did not have the authority to dispatch substantial reinforcements, and so he realized that the time had come to effect Urquhart’s wishes and pass command of the Division onto Brigadier Hicks. He set out in a Jeep with Lt-Colonel Robert Loder-Symonds, overall commander of the Division’s artillery, and after making their way through several small encounters between British and German troops, arrived at the 1st Airlanding Brigade HQ sometime between 07:00 and 08:00. Mackenzie informed Hicks of the situation and recommended that he send reinforcements into Arnhem as soon as possible.

However the question of leadership of the Division in Urquhart’s absence was by no means over. During Monday afternoon, Brigadier Hackett and his 4th Parachute Brigade arrived with the Second Lift, and Mackenzie knew that Hackett would not take kindly to serving under Hicks, who was junior to him in rank. Mackenzie was assigned the unenviable task of waiting on the 4th Parachute Brigade’s drop zone so that he could first bring Hackett up to speed on events, and also tell him that it had been decided that his 11tth Parachute Battalion would be detached from his command and sent into Arnhem. Hackett was understandably annoyed that his Brigade was being toyed with in such a flippant manner by junior officers, but he agreed to surrender the 11th Battalion, though requested that he be given command of the 1st Airlanding Brigade’s 7th Battalion, The King’s Own Scottish Borderers. Mackenzie had no authority to agree to this himself, but permission was eventually sanctioned by Hicks.

Mackenzie returned to Divisional HQ in time to receive a telephone call from Lieutenant-Commander Arnoldus Wolters of the Dutch Navy, who had been attached to the 1st Airborne Division to become Military Commissioner of those territories liberated by the airborne assault, and part of his role was to liaise with the Underground. He had already established contact with the Resistance and got in touch with Mackenzie to say: “There are sixty tanks coming down the road into Arnhem from the north. They are on the main road north of Deelen airfield.” Mackenzie was understandably shaken by this news as substantial armoured opposition had not been expected. He asked for a confirmation of this report, which came back an hour later. The prospect depressed him.

At about midnight, Hackett arrived at Divisional HQ, now at the Hartenstein Hotel, and an argument broke out between himself and Hicks over the present course of action. As this confrontation was taking place Mackenzie was in a room upstairs, attempting to sleep but finding that he could not. The Duty Officer, Captain Gordon Grieve, came in and informed Mackenzie that Hicks and Hackett “were having a flaming row”. Mackenzie immediately went downstairs with only one frame of mind; that his General’s orders were being challenged and he “intended to back Hicks in everything”. However when he entered the room, the two officers were much more relaxed and appeared to have settled their differences. The situation was resolved once and for all when Major-General Urquhart returned to his HQ during Tuesday morning, where Mackenzie greeted him with enthusiasm and quickly briefed him on the latest developments, adding, “We had assumed, sir, that you had gone for good”.

On Friday evening, Urquhart was concerned that the Allied commanders outside of the Division did not appreciate how desperate his position was, and so he instructed Charles Mackenzie and Lt-Colonel Eddie Myers, the 1st Airborne Division’s Commander Royal Engineers, to cross the Rhine and try to locate either Lt-Generals Browning or Horrocks to impress upon them the urgency for imminent relief. In addition he asked them to make a quick survey of the riverbank in order to pass on some details to the ground forces about where best to attempt a crossing. Myers had stashed one of the Division’s few serviceable rubber dinghies near to the river, which they floated along a ditch running alongside the river to find a suitable crossing point. A large sergeant-major appeared with a Bren gun and insisted on escorting them until, satisfied, the two men made their way across with Mackenzie rowing. Crossing the 200 yard wide river in broad daylight was a highly risky venture and a few loose shots were fired over their heads, but both men were able to reach the southern side safely. They cautiously looked around for a sign of their arranged Polish escort, and a short distance away they could see two steel helmets but were unsure whether they belonged to the heads of Poles or Germans. After a short period of hiding in a trench, Mackenzie elected to emerge from his hiding place to discover the truth, holding on to a white handkerchief in case he needed it, while Myers remained out of sight. It quickly became clear that one of the men was a Pole and the other was a British Liaison Officer. Bicycles were to hand, and so the four men rode to Major-General Sosabowski’s HQ. They informed the Polish General that 1st Airborne Division’s engineers were preparing rubber boats and would make every effort to bring his Brigade into the Perimeter that night. The sight of a small number of Household Cavalry vehicles in Driel heartened Mackenzie and gave him hope that he could be taken to Nijmegen that evening, however the road to the south was blocked and so he had to satisfy himself by using the radio sets inside one of these vehicles to contact Lt-General Horrocks. The long message related how badly the Division needed supplies of every kind, and also added that they could not hold out for more than 24 hours.

During the remainder of the day XXX Corps tried to clear a path to Driel to enable proper amphibious assault craft to get through to the Poles. This was achieved, but as the column of vehicles drew near the leading tank struck a Polish land mine. The commander of this unit complained bitterly to Sosabowski, only for another tank to similarly meet its end moments after. Mackenzie took on the role of mediator between the two parties and turned their attention to getting across the river. Lt-Colonel George Taylor, of the 5th Battalion, The Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry, was in favour of attempting an attack towards Arnhem bridge, but Mackenzie ruled this out as being impossible. Instead he drew up a plan to use two companies of the 5th DCLI to secure a crossing point so that two D.U.K.W’s could ferry the Poles across. Unfortunately the craft became bogged down on a steep and muddy bank and so the Poles had to improvise crossings using dinghies and crude rafts. Mackenzie looked on and was disappointed with the results.

By morning, the road to the south had been somewhat cleared, though German activity was still common. The commander of the vehicles that had reached Driel, Captain Wrottesley, decided to risk taking Mackenzie and Myers to Nijmegen in a small convoy of his armoured cars, thinking that they originally reached Driel under cover of mist and since these conditions were even more prevalent this morning, then there was no reason why they shouldn’t be able to achieve the same in the opposite direction. They had not covered much ground before they reached a crossroads blocked by the remains of a German half-track, destroyed on the previous day by the 5th DCLI. Wrottesley got out to navigate the convoy around it when suddenly a Tiger tank appeared down the road. The leading car got clear, and the second, carrying Mackenzie, fired on the tank which promptly returned the favour before backing away. The armoured car backed up sharply to line up another shot, but as it did so the road collapsed beneath it and the vehicle turned over. German soldiers then appeared, forcing the two remaining armoured cars to split up and locate assistance. Wrottesley climbed back into his vehicle and made a dash to Nijmegen. Mackenzie and the two-man crew of the overturned vehicle had only one Sten gun between them and were compelled to play hide and seek in a turnip field with the Germans, taking cover beneath some prunings while the infantry searched the field and called upon them to surrender. One man came so close to where they were hiding that if he had come any nearer then they would have been compelled to open fire and hope they could get away, but luckily for all concerned he turned away. The three men remained concealed for a time until they heard the sound of the armoured car return, together with a few tanks. They got to their feet and waved their berets to make themselves noticed, but the British, expecting a fight, opened fire on them. Luckily the shots fell wide and they were identified before a second volley could come their way. Reunited with Lt-Col. Eddie Myers in the third armoured car, the pair continued their journey to Corps HQ in Nijmegen.

Upon arrival Browning’s Chief of Staff, Brigadier Gordon Walch, observed that Mackenzie was “dead tired, frozen stiff, and his teeth were chattering”, and so a hot bath was immediately arranged for him. Browning regarded him and Myers and concluded that they were “putty coloured like men who had come through a Somme winter”. When he met Browning it became clear that no one had much of an idea what was actually happening north of the Rhine, and so Mackenzie related all the sorry details. He later did likewise with Lt-General Horrocks of XXX Corps, but Mackenzie returned to Driel feeling that he hadn’t fully conveyed the seriousness of the situation - a messenger bearing bad news is always presumed to be exaggerating. This lack of concern, together with the attention of the armoured drive being distracted by German interference further down the corridor, convinced Mackenzie that ‘Market-Garden’ was not going to have a successful conclusion. At Driel he visited Sosabowski to try and overcome one of the problems that he could foresee. Major-General Thomas of the 43rd (Wessex) Infantry Division had instructed his leading Brigade to take the Poles under their command when they reached Driel, and though Sosabowski led a Brigade that was intended to come under the command of ground forces when they were relieved, it was sure to sour relations if he, an experienced Major-General, were placed beneath a Brigadier in the command structure.

During the night of Saturday 23rd, Mackenzie was on the southern bank with his dinghy and was preparing to make his way back to Divisional HQ. The RAF were presently dropping bombs around the area, and so he decided to wait until the illuminated area fell dark. Shortly after a boat came from across the river, operated by an engineer-cum-ferry master, and for this trip his cargo was an RAF officer who had been shot down over the Perimeter and was now returning home. Mackenzie swapped places with the man and was taken across. On the other side he halted as he had been ordered to wait for a guide. The reasons for this were immediately apparent as he noted that, with its fallen trees, boat wreckage, and shell craters, the area was completely unrecognizable to the one he had left several days previously. Mackenzie had a dilemma over what he should say to Urquhart as he was torn between the cheerful views of what Browning and Horrocks thought would happen, and his own depressing estimation of what he knew would happen. Deciding that his commander had plenty to worry about without being distracted by a matter over which he had no influence, he opted to sound optimistic, omit the realities of the situation, and insist that reinforcements were on the way. He withdrew across the Rhine with the rest of the Division 48 hours later.

For his actions at Arnhem, Mackenzie was awarded the Distinguished Service Order.

His citation reads:

At ARNHEM on the 22nd September this officer who is G.S.O. 1 of the division, was sent from the perimeter across the River LEK [The Lower Rhine] to contact troops of the 2nd Army. The crossing was made in daylight in a rubber boat in the face of a certain amount of enemy fire. He made his way to the formation headquarters south of the river through country which had not been completely cleared of the enemy. As a result of this vital information which he carried, plans were made for the relief of the division. The following day Lieutenant-Colonel Mackenzie made his way back to the division again recrossing in daylight. The services rendered by this officer throughout the action at ARNHEM were of the highest order and his leadership and initiative both on the occasions mentioned and subsequently during the withdrawal were a contributing factor to the successful outcome of the operation.

After the war, Charles Mackenzie remained in military service, in a series of Staff Appointments, and rose to the rank of Brigadier.

He was made an Order of the British Empire in the New Years Honours List 1950.

In 1956 he published a book, It Was Like This!, detailing the battle from his perspective.

He commanded the 154th (Highland) Infantry Brigade, Scottish Command, from September 1954 until February 1957, and retired in 1958.

Charles Baillie Mackenzie died in June 1991 at Inverness in Scotland.

By Bob Hilton, uploaded by Sam Stead.

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.