Staff Sergeant Arnold Baldwin was a glider pilot of 20 flight, B squadron, No.1 Wing, the Glider Pilot Regiment. He flew over Normandy and Arnhem. His copilot for much of the war was Joe Michie.

Staff Sergeant Baldwin joined up with Joe Michie in the Spring of 1944, when they were both training on exercises for Operation Overlord and the Coup de Main component of the Merville battery raid which would involve three Horsa gliders. When the time came to fly, it was discovered very late that 4 gliders had an arrester parachute and 4 had Rebecca-Eureka devices, but none had both, a problem that had to be very quickly solved.Then the allocation of the Horsas took place and things got worse; Baldwin recalled to his regret that there were "two brand spanking new Horsas and one beat-up old one. The Major (Toler) did the only fair thing he could do; three sticks, the fellow drawing the short stick getting the old one. I need not tell you who that was". On June 6, Baldwin and Michie set off for Normandy in Glider 28A (c/n) containing a section of the 9th Parachute Battalion led by Lieutenant Smythe. Their tug pilot was Flight Sergeant Richards in an Albemarle. They were part of three Horsa/Albemarle combinations from 297 Squadron, Brize Norton. Their mission was to land a special force of the 9th Parachute Battalion inside the defences of Merville gun battery to destroy the heavy calibre guns stationed there, which threatened the seaborne invasion at Sword beach, 8 miles away.

Unfortunately, the Merville battery mission did not go remotely to plan for Michie and Baldwin. The fate of glider 28A was described as follows:

"This combination also ran into very bad weather shortly after take off and in particular a very violent Cu.Ni. [cumulonimbus] cloud and torrential rain over Odiham. S/Sgt. Baldwin and the Tug Pilot did all in their power to keep the combination together but just as they were emerging from the cloud the rope broke and S/Sgt/ Baldwin made a successful forced landing at Odiham without the help of A.S.I. or altimeter owing to the Pilot head having been removed by the rope. So violent had been the movement in the cloud that the rope had cut into the main plane which was found to be severely damaged".

Michie described the flight thus:

"We headed for a very thick black cloud which Dennis Richards, our tug pilot, managed to avoid, great lumps of cumulus which looked pretty threatening at night. Then eventually he said over the intercom through the rope, 'I'm sorry we can't go round the next lot, we'll have to go through it', so we went straight into this large black cloud [...] we came out under this black cloud which was like a ceiling and just as we came out, the rope parted with a sigh more than anything".

Baldwin also gave his own account:

"We began to trundle forward. After using the usual amount of runway I pulled back on the stick but there was no response. A little further on I tried again - still no response. Then Dennis asked me rather sharply over the intercom, when I was going to lift off. I told him I couldn't get off. A few more yards and then Dennis said with great urgency that if I didn't lift off we would be going through the hedge at the end of the runway. At that moment she lifted very slowly and we both cleared the hedge. Almost immediately the port wing began to slowly drop. I tried to correct it with the aileron but it still continued dropping so I applied opposite rudder. At first there was no effect, and I feared that, being so near to the ground, the wing-tip might strike, so I steadily increased right rudder till it was fully extended and slowly the wing came up again. Then I realised that we would have to make the whole flight with full right rudder. I tried to speak to Dennis on the intercom cable running through the tow-rope, but there was so much noise on the line, possibly caused by the strain on the tow-rope, that we could not hear each other. Before long my right leg became so painful that I asked Joe to put his foot down. Fortunately, he was a hefty lad with stout legs and he was able to take most of the strain off my leg. We flew like this for some time in fairly clear conditions, but the effort to keep such an unstable aircraft going was a great strain on both of us and the inability to tell Dennis of our problems made matters worse [...] How long we were in that cloud I cannot tell, but it was quite the most frightening experience I have ever had. We bounced and jumped around with no idea of our relationship to the tug and a terrible fear that we could go completely out of control at any second. After what seemed like ages we emerged from the cumulus and there, right ahead of us and in the right position, I could see the tug [...] I felt physically sick, Although we had only been training for this job for about three weeks, all the previous months of training that led me to feel that the end of this flight would mean France, and at first I couldn't accept the fact that we were off tow and still over England. I slumped in my seat feeling utterly dejected and said to Joe, 'I dont give a f... what happens now'. When he responded, with a great deal of feeling 'Well I do and I expect those fellows in the back do as well', I came out of my trance and began to think about what to do. The ASI read 140 so I eased back on the stick very gently and had a look around. There, to my amazement and great relief, I saw a runway's lights just off our starboard wing-tip. Fortunately, I had a good deal of night-flying experience and it looked like a normal circuit and landing to me. We were flying cross-wind to the runway and I thought 'Just continue a bit further on this leg, then a down-wind leg, another cross-wind and a nice turn in to the runway.' However, I had barely commenced the down-wind leg when the runway lights went out. I thought they must be flying Ops to France and wanted no strangers coming in. It was now very dark, the moon being obscured, but I felt pretty optimistic now about a safe landing. Another look at the ASI still showed 140. I knew that couldn't be right, but I also knew with our overload that we would have a much higher stalling speed than normal so I did nothing to change the glider's altitude. Turning across wind when I judged the aerodrome to be a little way behind us, I made my turn and then again, as I believed, into the wind. We now had very little height and I was pretty shaken when I dimly saw the outline of a building on either side of us. By a very lucky fluke, we passed between two hangars. Then we were bumping along the grass and I had a similar loss of concentration to that when the tow-rope had broken. Fortunately Joe had his wits about him and quickly applied the brake. Even so, we made a long run down the field before stopping".

They had landed at RAF Odiham, Hampshire, at 3.20 AM and had to take off again the next day by air. Nevertheless, the assault on the Merville battery was a qualified success, as the 150 paratroopers collected by Lt. Col. Otway managed to take the gun casemates and blow up most of the guns firing towards Sword.

Later in 1944, Baldwin was preparing to fly to the Netherlands for Operation Market Garden; on September 17, it was time to set off towards Arnhem. He and Michie were back together in a Horsa glider (aircraft number PW703 chalk number 292) towed by an Albemarle flown by Pilot Officer Richards to L.Z. 'S' near Wolfheze. Their passengers were from the headquarters of the 2nd Parachute Battalion and they also carried a jeep and trailer. Baldwin's departure from RAF Manston was recalled by Staff Sergeant Arthur Shackleton:

"Fancy hoping you could go to war, we must have been mad or maybe someone had doctored our tea. I was just on the tow path talking to Arnold Baldwin and Joe Michie, when our load approached led by Lieutenant Colonel McCardie [...] Our glider was first on the runway as we were first to go, Arnold and Joe were second carrying the rest of the Battalion Headquarters staff"

During the Battle itself, Baldwin and Michie spent most of their time attached to 20 flight and Captain Angus Low. Michie was armed with a Sten gun. They spent Wednesday and Thursday (20 and 21 September) dug in to the east of the tennis courts at the Hartenstein Hotel. They were then seconded to the 21st Independent Parachute Company headquarters, where they were to keep a "sharp lookout for a possible German attack" (Baldwin). Later they returned to the Hartenstein and had to endure heavy shelling every morning, as Shackleton describes on Saturday 23 September:

"Later on in the day a shell landed on the lip of our trench and we were buried up to our waists in sandy soil and rendered as deaf as posts. On clambering out, we dived into the next trench and finished up with Arnold Baldwin on the bottom and Joe Michie on top of him. Me on top of Joe and Major Toler on the very top, with his legs sticking out".

An entry in 'B' Squadron's War Diary for 23 September complements this account. It reads:

"Very heavy mortaring and shelling for four hours continuously. Jeep set on fire. Several dug outs blown in. No one injured. Each section in turn has been occupying house outside our perimeter. S/Sgt. Thomson's Section now occupies the house by Major Wilson's H.Q. S/Sgt. Thomson wounded by Mortar fire in getting to position. S/Sgt. Baldwin taken over. Still no definite news of Troops crossing the river other than a few Poles. Water getting very scarce but still obtainable from well."

Later, in a house on Pietersbergseweg, Baldwin and Michie began to suffer the effects of starvation, which combined with the stress of the Battle was leading to delirium. A soldier named Harry Crone, who was in the house with them, threw a grenade into the scullery at a German who was peering in, without much thought for the consequences. Moreover, shots were being fired across the street despite the possibility of alerting the enemy. Shortly after this they were ordered to occupy empty slit trenches on the other side of the road to repel a tank attack, an order that went down like a lead balloon. After returning to the house prematurely against orders, Baldwin (now technically in charge) was reprimanded. Mercifully, the order to withdraw arrived at the moment Baldwin had technically disobeyed his.

At 0130 on 26 September, the glider pilots were withdrawn from the Hartenstein tennis courts where prisoners were being held and made their way to the boats on the river. As they left, Michie noticed that a rather soggy and opportunistic German man had slinked into the queue to leave. They took him with them.

On September 28, Michie and Baldwin joined the massive convoy of vehicles withdrawing from Nijmegen towards Brussels:

"We were trucked along the corridor, which was not yet totally secure, passing many knocked out tanks, with Typhoon 'cab ranks' overhead. Finally excited mobs were cheering us as we entered a devastated Louvain. The next morning we took off from Brussels".

On September 29, after the fighting withdrawal from Arnhem had now been seen through, Michie and Baldwin flew back to England from Brussels. Michie described this experience in Glider Pilots at Arnhem:

"As usual with the 'Dak' the wings were flexing, would they fall off? Nobody seemed to have heard of post traumatic stress in those days. We landed at Lympne, then on to a USAAF station. Finally trucks to Brize Norton."

After the war, Staff Sergeant Baldwin was awarded a mention in dispatches dated 8 November 1945 for bravery in North-West Europe.

Written by Alex Walker with research from Bob Hilton

Compiled with information from:

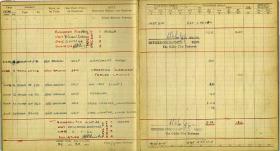

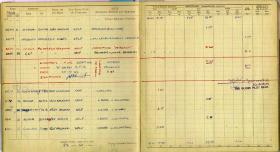

Michie's flying log book

Email correspondence between Michie and Bob Hilton

History of the World's Glider Forces, Alan Wood

The Day the Devils Dropped In, Neil Barber

Glider Pilots at Arnhem, Mike Peters and Luuk Buist

The Chalk Collection Facebook page

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.