James ‘Jimmy’ Cooke was born on the 9 December 1921 and came from the Basingstoke area. He initially enlisted in the Hampshire Regiment on the 15th June 1939, but on the 13 December 1939 he transferred to the Royal Artillery.

He volunteered for Airborne Forces in 1942 and joined the 1st Air Landing Recce Company.

Jimmy was allocated to ‘B’ Troop and saw service in North Africa and Italy, May – September 1943.

On the return to UK, in December 1943 he was billeted in Ruskington, Lincolnshire. He was part of the first main group of Recce Squadron men sent on parachute course 109, at RAF Ringway, 24 March to 9 April 1944. His instructors comments: Quiet, alert. A very good parachutist.

On Sunday, 17 September 1944 he flew on a Dakota C47 aircraft from Barkston Heath aerodrome to DZ ‘X’ near Heelsum in Holland as part of ‘Operation Market-Garden’.

As a member of HQ-Troop he was assigned to Lt ‘Jimmy’ Pearson to make up a jeep crew, and on Monday, 18 September, they were attached to ‘C’Troop and then had the unenviable task of recovering the dead from the ambush the day before.

‘When the bodies of the dead had been recovered, each was wrapped in a grey army blanket and laid to rest in temporary graves in Duitsekampweg. A short service was conducted by one of the Roman Catholic padres, and Jimmy Cooke can still recall how, at the end of it, the padre turned to them and said, “I think you've done your bit - now I’ll do the rest.” Thereafter, the recovery group rejoined the Troop in the allotted positions, which extended north from Mesdagweg. It was not all stationary defensive work, however, for there were still opportunities for reconnoitring, and patrols were sent out. Cooke recollects accompanying his officer, Lieutenant Pearson, in three reconnaissance jeep sorties up the Wolfhezerweg to its junction with Amsterdamseweg. This was the place at which Dobie’s 1st Parachute Battalion had suffered such heavy casualties on the previous evening, and the dead were still lying on the road. Nor had the danger by any means passed away, for the Germans still seemed to have a mortar ranged on the crossroads and, from time to time, they would suddenly plaster it with a cluster of bombs. Cooke remembers the feeling of vulnerability that they had on that open crossing and the consciousness of being in what was obviously a potential hot spot. It was there, on the third sortie, that they narrowly escaped capture: “Mr Pearson took three of us back up to the crossroads,” says Cooke, “where we harboured the jeeps under the trees. Two of us then set off with him on foot to reconnoitre the main road to the west. Mr Pearson was about six yards ahead, then came the other men, then myself. Suddenly I saw him signal back to us before disappearing fast into the woods. Where we were, we didn’t have any cover at all, so we lay down in the ditch and pretended to be dead, like all the other British soldiers who were lying around. It was an SS patrol of about twenty men, walking on a path beside the ditch, and they actually marched right past the chap who was lying down further ahead of me. About ten yards or so before they got to me, they crossed over to the other side of the road and into some gorse. We lay faking ‘dead’ until they’d passed on a bit, then made as quietly as possible for the shelter of the woods. Fortunately the chap on the jeep had spotted what was happening and came up fast to collect us. By then, Mr Pearson was nowhere to be seen, but he managed to get out all right, although he had to run all the way back to our base on foot.”

Whilst these hazardous ‘recce’ sorties were taking place, the remainder of the Troop continued to maintain static positions of defence at the landing zone, in anticipation of the arrival of the second lift.’ [1]

On Tuesday, 19 September ‘C’ Troop were ordered to carry out a reconnaissance of the Ede to Arnhem Road. The route was mostly along tracks and through some fairly thickly wooded country.

‘As a result, crews had to walk in pairs ahead of each vehicle, with only the driver bringing it on slowly behind. Just over a mile and a quarter was covered in this way, until eventually they encountered the unfinished road works for the new east-west highway. It was there that they got a hint that their progress might not have gone unmarked. The small disquieting episode that occurred is still vividly recalled by Jimmy Cooke: “Palmer and I were leading the Troop, and walking about a hundred yards ahead of the vehicles, when we found we had to go through a kind of culvert. It was when we got underneath that I noticed a fairly big tin, like a petrol can, sitting there with a bag on top. As I passed it, I put my hand on it and, although it was completely in shade, the sack still felt warm to the touch. I realized that someone had been sitting there only seconds before. I also wondered if whoever it was could have us under hidden observation and that I might at that very second be lined up in his sights. It was not a pleasant thought.” Despite the obvious proximity of the enemy, the Reconnaissance men passed through without mishap, investigated some abandoned workmen's huts in the immediate vicinity and finally reached the road. Once there, Lieutenant Pearson climbed a tree, from which vantage point he was able to observe that, as far as he could see, enemy armoured vehicles were moving slowly from the west in the direction of Arnhem. Behind them the woods whispered with the sound of movement and the uneasy thought arose that they had, perhaps, unwittingly walked into a trap.’ [2]

A decision now had to be made about how the Troop were to get back to their own forces at Oosterbeek, via Wolfheze. The plan was to drive out onto the road, when there was a gap in the German traffic, and drive as fast as they could. This worked well for a while, and then the Germans started to fire on them.

Most of what then happened was witnessed by the five occupants of the fifth jeep. At the wheel was its commander, Sergeant David Christie, and beside him, with responsibility for the Vickers “K” gun was Lance-Corporal ‘Bert’ Palmer from Portsmouth. In the back were Troopers Cooke, McSkimmings and McCarthy. At twenty-three, ‘Jimmy’ Cooke, a gardener from Basingstoke, was the oldest man in the group; he carried a Sten. McSkimmings also had a Sten, whilst McCarthy manned the Bren gun. As his own jeep approached the trouble area, David Christie recalls how the thoughts of home and family that had come into his mind only seconds before were as speedily dismissed by the reality of a bullet zipping past his head. As he was later to remark, with laconic Scottish understatement, “It brought me back to the matter in hand.” For a reconnaissance section, that still meant trying to fulfil the primary role of estimating the extent of the German opposition, and Christie recollects that, even as he drove into the conflict, his brain was instinctively recording enemy strength as in the region of two companies. “Hundreds of them, laid three deep on each side of the road,” is how Jimmy Cooke remembers it, while Christie adds, “I can remember the ditches at both sides of the road, and they were strung out along them about two yards from the edge, firing at point blank range. I could have spat on the Jerries, they were so close.” Suddenly, as the convoy sped on, the third vehicle was hit. From his own position further back, Cooke saw what happened: “It was like hell let loose. I saw Mr. Perason’s jeep go right up in the air. It must have been hit by a shell, because it just blew up and bits of it landed all over the place.” And accompanying those kaleidoscope images of destruction, death and injury was the raw sense-assailing sound of the firing. The noise was deafening, as each jeep’s complement in turn added its own contribution to the growing crescendo of fire. For Cooke and his comrades it reached a frightening intensity as Christie hurtled the vehicle into the thick of the fight. In the rear, Cooke and McSkimmings sat back-to-back, indiscriminately emptying their Sten magazines as fast as was possible into the rows of Germans lying in the dappled shadows to each side of the wooded road. McCarthy, too, was firing his Bren, whilst, in front, hunched over the Vickers “K” gun, Palmer hammered away at a frenetic thousand rounds a minute, with a barely perceptible pause for changing the [magazine] drums. All around, the acrid pungency of burning cordite tainted and polluted the air, as the fierce engagement mounted to its climax. By then, the speed of the vehicles had increased to beyond sixty miles per hour, and it was only luck, together with the overall skill of the drivers that was preventing a multiple pile-up from developing. But it was at that point that some of the luck ran out. Crouched down in the driving seat, with his head ducked low behind a ration box strapped to the bonnet, Christie was steering with the left hand only. It was a position [that] afforded him the illusion rather than the substance of protection, but it particularly suited Palmer, who could then fire the Vickers “K” [gun] over his driver’s head. Suddenly, to Christie’s dismay, he realized that the jeep in front had run into trouble and begun to slow down. There was only one course [that] he could take. It was a split-second decision, but with the action at its most intense, there was no choice but to pull out and pass. “All the time,” he recalled, “I could see red, blue and green tracer flashing past my eyes. Palmer had just put on another one hundred round magazine [drum] and was firing again. I pulled closed to the left and ran level with the vehicle in front. Thank God the driver had the sense to keep it on a steady course. I was doing seventy now. My nearside wheels ran up the grass verge. I saw a little white milestone affair popping up through the grass in front of me. Christ knows how I missed it, but I did. I swung into the centre of the road again, and felt a bullet snick my left elbow. A tree was lying across the road in front of me. I swung to the side where the bushy top of the tree was and never slowed down. It was now or never. Luckily the tree was fairly thin and I got through.” The evasive move by the two 7 Section vehicles was registered up ahead by Cooke, at just about the time when he realized that Raymond McSkimmings was dead: “I noticed McSkimmings had a hole in his head – a tremendous hole. He was much taller than I was, and the shot had come from my side, passed over my head and caught him.” McSkimmings, only nineteen years of age, must have died instantly, for closer inspection revealed he had received a burst of machine-gun fire, and Cooke reported finding his brains all over the map cases and on McCarthy’s Bren. Oblivious to all this, David Christie raced on, to emerge out of the green tunnel into open country. To the right, immediately ahead, lay the junction with Wolfhezerweg and the turn to the South. “As far as I can remember,” said Christie, “my accelerator foot was still hard on the floor when I swung round it, but we just made it. When I was straightening up after the bend, I heard something crash on to the road. I looked round and found only two men in the back of the jeep. ‘Who was that?’ I asked, ‘McSkimmings, Sarge,’ came the reply.” There followed a swift shouted exchange between Christie and Cooke, during which time the sergeant was slowing his vehicle to a halt. On Cooke’s emphatic assurances that McSkimmings was clearly dead before falling off the vehicle, Christie then depressed the accelerator again and sped off down Wolfhezerweg.’ [3]

Making it back to the main Squadron positions Cooke and the others were absorbed into the defensive positions that were being taken up around the area of Oosterbeek as the final perimeter being held by the 1st Airborne Division. On Friday, 22 September contact was finally established with the relieving forces to the South of the River and artillery support was now being brought down on the German Forces opposing them.

‘Jimmy Cooke, who was at the Squadron HQ positions, has personal memories of those shoots which, heartening as they were, did induce a considerable amount of fear, especially as many of the shells landed very close to the British trenches. “There was a house just over the road from us,” he says, “and it must have been hit a dozen times or more, for I can remember an old car that kept being put up in the air as the shells landed. We could hear the ‘wump-wump-wump-wump’ in the distance, and then we’d wait in the silence for the loud whistling overhead and the crashes as they hit their targets - but, my God, they were close!” Cooke’s worry, like that of all the others, was that the guns at Nijmegen only had to drop a fraction for the shells to land on top of them.’ [4]

The next day an even more frightening experience awaited them, as they held on their positions and trenches on the Western side of the perimeter.

‘All morning, there was continuous noise around the Divisional area and, as an obvious prelude to yet another attack on the British perimeter, a fresh mortar barrage came down at about 1430 hours. It was during this particular “stonk” that David Allsop was himself wounded by shrapnel, but made do with first-aid in order to stay at his post. To make matters worse, a terrifying addition to the German onslaught was introduced. “That was the day,” Jimmy Cooke recalls, “when they brought the flame-thrower up, and I think it was that which frightened me more than anything else. It fired out of the wood, and those great tongues of flame, about twenty feet long, travelled over our slit trenches and landed at the back of us. We knew when it was going to be used, because they had it on a tank, and we used to listen for the tracks coming up. These things struck fear and terror into everyone, because we reckoned that they only had to dip down a little, and that would be it.” [5]

Luckily for Cooke, and others in the area, these flame-throwing tanks were either knocked out or driven off before they could inflict serious damage on the British defences.

After nine days of severe fighting, he withdrew with the remnants of the Squadron back across the Lower Rhine on the night of 25th/26th September 1944.

He was promoted to Lance Corporal in 1945 and took over as one of the Despatch Riders (Don R’s) for the Squadron and went to Norway as part of the liberation force, May – August 1945.

He was awarded the Efficiency Medal (Territorial) in August 1946, the month after he was discharged to the Z (T) Reserve.

After the war he settled in Ruskington, married, and became a Traffic Warden for the nearby town of Sleaford.

He is mentioned often by both Recce Squadron veterans and Parachute Regiment Association members for his smartness on parade with the Lincoln Branch P.R.A. Standard at official events, such as the Annual Memorial Service at St Martin in the Fields in London.

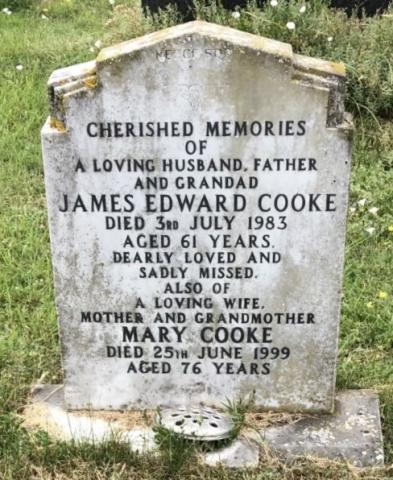

‘Jimmy’ Cooke died on the 3 July 1983, aged 61 years.

LAST POST. 1st Airborne Recce Squadron Newsletter, No 10, November 1983.

Tpr JE Cooke. 1st Airborne Reconnaissance Squadron [HQ-Troop] and Arnhem Veteran. Passed away in July of this year.

‘Jimmy’ was the Standard Bearer for the Lincoln Branch PRA for several years. He was a Traffic Warden for many years and was well respected by both Recce Squadron members and members of the Sleaford Constabulary and colleagues with whom he worked.

The service for Jimmy was held in the Church at Ruskington and attended by members of the Recce Sqn and the Lincoln Branch PRA and members of the Sleaford Constabulary. Being a military funeral an Honour Guard, composed from members of the above, lined both sides of the path that led from the Church down to the road. His coffin, overlaid with the Union Jack with the Recce wreath made in the shape of the Recce cap-badge resting on the top, was borne by members of the Sleaford Constabulary.

Jimmy was laid to rest in the Ruskington Cemetery where a short service was held that included the Last Post and Reveille being sounded.

Jimmy will be sadly missed by all who knew and worked with him.

NOTES:

[1], [2], [3], [4], [5] ‘Remember Arnhem’ by John Fairley. Published by Pegasus Journal. 1978.

Created with information and images kindly supplied by R Hilton.

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.