The diary of “our” war – 17 September 1944 to 5 May 1945.

V.M.L. Mekkink van den Brink.

Translated by M. Honcoop & E.W. Robbins.

Sunday morning 17th, September 1944.

“If only something would happen”, was the lament of the whole of the Netherlands over the last months – that is – the parts of Holland still remaining under German occupation. The strain became almost unbearable during the weeks preceding 17 September 1944.

Even we, Uncle Jo, Aunt Tine, the boys, Hans and Joop and I, their mother, had that yearning, on this unusually bright sunny Sunday. If only something would happen to end this dreadful situation!

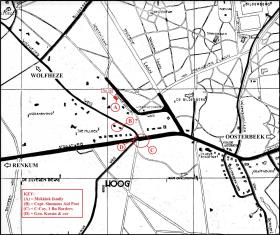

Early this morning, we heard the air raid siren moaning at Arnhem, audible to us some 15 kilometres away, blown on a strong wind. This strange “other world” sound was alien to us, as we live on a quiet country lane, well away from the populated areas of the vicinity; almost like living in “no man’s land”. On the one hand, we were far removed from the grey stone of the houses in the town and as well, half an hour’s walk from the actual centre of Oosterbeek. The woods, which surrounds us, with its seasonal, ever changing green-bronze leaves was our closest neighbour, and comrade, faithful and stolid in its friendship.

Close to eleven o’clock this morning, while we were taking our cup of “substitute” coffee under our favourite birch tree in the garden, the birds were loudly singing in the trees under a clear blue sky. This beautiful setting seemed to augur a wondrous change about to alter our lives. But how could we know this glorious Sunday morning, that “our” pace was about to be disturbed – how much was about to happen!

The boys were busy building a tree-house, we three grown-ups were curled up in our easy chairs, with a book, while other people were huddled in their dark cellars awaiting the “all clear” signal.

Around noon, there was, evident to our ears, the rumble of a large number of heavy bombers overhead. The boys, in great enthusiasm came running home, to share their elation with us – “Look mum, look up, there are coming more and more planes!” Overhead, the sky was full of “silver” butterflies, scintillating in the September sun. Without realizing the import of the event, the sight was fantastic. Our strongest hopes, suddenly became alive, our faith in deliverance from our oppressors was reborn, we offered this aerial armada a personal salute. Formations of planes seemed to converge on our area from all sides and suddenly the first bombs began raining down on the village of Wolfheze, approximately one kilometre west of where we were enjoying our peaceful Sunday morning.

Realizing with fright, our proximity to the bombing area, we immediately took shelter, kindly offered by our neighbours in their root-cellar. Breathlessly we followed the rumbling of the exploding bombs - almost as if a wild thunderstorm was passing overhead. Stealing a quick look, outside our shelter, there were formations of huge four-engine bombers in units of six, followed by groups of fighters; ready to protect them from enemy planes.

In our opinion at the time, we regarded this bombing of Wolfheze as just another in the growing number of cities and towns being subjected to this phase of the war. After about an hour the bombing appeared to diminish, or fade into the distance like that thunderstorm. At this moment, we dared to slowly emerge from our shelter, foot after foot, groping like chickens just leaving their coop after a long confinement.

Yes indeed, the trees were still there, the sun was still up in the blue heavens and a few birds were even singing loudly, all around us seemed as usual and this helped us to regain our original relaxed mood and congratulate ourselves on having come through our ordeal unscathed.

As it was now early afternoon we even felt a small pang of hunger, so we returned to our home and I began to cook some lunch. Hardly had I started this chore, when we became aware of an unusual incident on the road. A woman from Wolfheze and her young son, were hurrying along the road away from that village, obviously in a state of shock – at first not even able to speak. We gave her something to drink, and asked her to come into the house, but this she refused, stating she wanted to move on to relations in Oosterbeek. She told us that her whole village was afire and that help was needed, that many people were trapped in the ruins of their homes. As a result, three of our men hurried on their bicycles to the village to help. About half an hour later, two of them returned. Indeed Wolfheze was afire, and they stated they were sent back because of the danger. Not long after their return, the bombardment was renewed and we rushed back again to the cellar. Shortly after attempting to relax in the shelter, the third man who had rushed to the aid of the village returned in great in a great state of excitement – he brought us the joyous tidings that he had seen the first of the parachute landings of the English.

About four o’clock a now strange silence fell upon us! Were the English there – or were they not? In order to find out as soon as possible in the evening we ‘liberated’ our radio from its hiding place, so that we could listen to the B.B.C. evening broadcast to learn the true facts. Shortly after the radio was prepared for the news, we heard, coming from the main road, the sound of many auto engines and shouting, then the sound of a motor near-by – then the sharp crackle of shooting, and after that silence again. (The next day we could reconstruct these sounds. From the vicinity of the shots we saw a German staff car with two dead German generals, one obviously killed instantly, the other as he apparently attempted to escape.)

Overhead we could see, stately and elegantly in formation, lines of large gliders. Obviously the landings were still in full swing. Were the English in our neighbourhood? As our home was comparatively isolated in the woods, we could only draw conclusions from nearby sounds and the movements in the sky.

Consequently, around six o’clock, two of us decided to sneak along our bush-road in the direction of Oosterbeek, to attempt to find out more of what was happening around us. We were accompanied by two young boys trying to return to their home in the large farmhouse close to the Utrechtseweg. As the time passed by, with no return to us of any of the four, our fright over what might have happened to them increased; were the Germans in the vicinity? Had our party been take prisoner? Would the English have held them, worried of the possibility of spies? Minutes turned into hours, and the wives of the two men from our party who had gone on patrol became deeply upset. Finally we saw them, sneaking back with extreme care. We could hardly wait for their return, to hear of their findings, but knew that if they were seen by fighters of either side, they could be fired upon. When they finally returned, we learned that the landings had been successful, and the English had established a Command Post in the large farmhouse, the home of the two boys who accompanied our two information seekers. The boys found that their mother and the two younger children were safe. All fear gone – we were free!!

When our two men came face to face with the first English, by the farm-house, they were advised not to move about on the open roads, especially during the night, for their own safety. At four o’clock these paratroopers had landed at Heelsum and had quickly advanced on the main road towards Oosterbeek, and strangely enough, without encountering any Germans! But, the highlight of our men’s meeting with the ‘Tommies’ was being offered their first cigarettes in four and half years!

About five o’clock a certain Mr. ‘B’ decided to visit his sister-in-law, Mrs. ‘B’, who was one of our neighbours. As he progressed along the main road from Oosterbeek, he happened to pass two German patrols, who had just come together, and overheard some words - first party: “are the English nearby, yes or no?”- “Yes, there are many”, replied the other, as he passed. Surely, the second patrol were absolutely right, for, indeed a short distance further down the Oosterbeek – Heelsum road, he encountered numbers of red-bereted ‘Tommies’, cautiously approaching. Without certain knowledge at that moment, the German patrols were rapidly arriving at an historical moment. Early that evening there was sound of heavy fighting, so again to the cellar! By now we were seventeen souls, jammed into that small, confining area. The adults, sometimes dozing, crammed together on hard wooden benches, the youngsters lying above us on small bunks.

[Monday, 18th September 1944]

Towards morning, the shooting died down and by day-break all seemed quiet, so we crept again out of our dark burrow, towards a new day, that was to be full of surprises. The first surprise – we learned our water supply had been cut off – not to worry, we had taken the precaution the previous day to fill our bath-tub, as had our neighbours. Next surprise – our two young farmer boys arrived for a little visit, to inform us that the British had taken over all but a few rooms in the big farm-house. [1] But biggest surprise, they also brought for our breakfast, our first REAL tea and white bread in years. Towards noon, there appeared overhead like huge blossoms, many coloured parachutes. Each carrying, suspended beneath, a large container or a wicker basket. As some fell in our gardens, Jopie, our youngster, retrieved the first basket. What would it contain? Food, clothes, ammunition? Did we dare open it? Because of the obvious operations, we felt not allowed to open it. We advised the Command Post of the dropping and soon a few ‘Tommies’ came to collect it. It contained only ammunition, however, we were proud to be able to help our liberators. Almost immediately, a new wave of parachutes appeared overhead. We were so excited at being able to help that we scarcely heard the renewed sounds of fighting. As the shooting became heavier, shrapnel and bullets began flying around over our heads, so, back to the shelter.

Somehow, we did not want to hear it: were we not already freed? Our enemy had been disposed of, by our liberators the English – so we thought! The attack appeared to come from beyond our perimeter, but, as before the noise of battle again died away. After waiting a prudent interval, and at the urging from our friends from the big farm-house, we proceeded towards the main road to Oosterbeek. As we came in sight of the ‘Utrechtseweg’, we saw a large group of local people, waving flags and presenting flowers to a long column of advancing British paratroops. It seemed like a triumphant parade of the victors, our gallant red-bereted English ‘Tommies’ wearing bright yellow scarfs. Many were riding on khaki coloured military vehicles and motor bikes that they had obviously brought with them in their gliders. Some carrying wounded soldiers who, along with their comrades were answering the local welcome with wild cheering – our valiant liberators! We could not but be inspired by their mood of enthusiasm, and even the shyest of the bystanders joined in singing in loud voices, the English National Anthem. The immediate goal of this column was the town of Oosterbeek, where they could still expect resistance from the enemy, and the last section of the group turned off to surround, and give protection to the farm-house which was currently their Command Post.

With our continuing enthusiasm, we marched along beside this group, accompanying them to the farm-house. They were obviously tired and warm from their march, and the farmer’s wife had prepared some fruit drinks for them. With pails, we fetched fresh, cold water from the pump, almost a kilometre away, and filled their water canteens. It was a wonderful experience, to again speak English, enjoy the warm friendliness of these young men, also to share their cigarettes and delicious English chocolate.

The ’Tommies’ proceeded to tell us some of their battle plans – that a large land force under General Dempsey, advancing overland, would join up with the paratroops. Tonight the victory will be secured, the troops united, and our liberation preserved. With these words we knew that our fervent hopes would be realized. At ten o’clock that evening we returned to our home, singing at the top of our voices, “O, dierbaar plekje grond” (“O, beloved little land”). To the English it was familiar to their ears – these words are sung to the tune of the English National Anthem. Our mood of elation seemed at one with the peace of nature on our country road.

Tom T, a student of English at Arnhem, because of this study had been forced underground (at this time, all students were liable to forced labour in Germany – consequently Tom chose to go into hiding). His hiding place at this time was with our next door neighbours, and when his situation and knowledge of English became known to the ‘Tommies’, he immediately offered his services to them. The following day he was taken into their services as an interpreter. Eight months later we met him again at our forced evacuation centre at Harskamp. We learned he had just been discharged from hospital – for the second time! And, through the help of the Red Cross had been able to finally trace us to our new address. He told us that on 20th September he was wounded in the eye by a one centimetre splinter from a grenade. He was at first treated by English Medical Doctors to the extent their limited facilities would allow. Then, together with other wounded, when the English were forced to retreat, he was passed on as a wounded civilian to the German Medical Authorities. “In my physical condition, I felt that they, the English, could not have rendered me a better service”, he said. To ill to be transported on the retreat of the English, his only wish was ‘peace and quiet’ or death! He continued, “For three days I had the former, as they left the splinter in my eye, to treat other more urgent cases – then it came my turn. They removed the splinter, which I will always keep as a souvenir, and apparently I was unconscious for almost a week, because of the pain I suffered, with no narcotics available to ease it. I came to in a hospital in Apeldoorn, where after a great deal of formalities, I was turned over to Dutch Doctors. When I had recovered sufficiently, I was taken in a round-up by the Germans and with hundreds of other Dutchmen, packed like animals in cattle cars, and moved to Zevenaar. Shortly after arrival in this horrible camp, I was able to find a way to escape. As I knew by now that it was impossible to return to my home in Arnhem, and that I had contacts in Apeldoorn, through my original hospitalization there, I decided to make the long trek back. Like many other Dutchmen at this time of the war, my shoes were in poor condition, the soles almost completely worn out, and certainly not really good enough for the long journey. But, I had no other choice. As a result of my determination to press on, my feet began to suffer. First a few open cuts and bruises, then infection of these open sores, then after long furtive weeks of travel, as I arrived in Apeldoorn, my feet seemed to be rotting away. Thus my second time in hospital, and only after my discharge was I able to begin my search for you”.

This short story is only one of very many, that involved our countrymen in great ordeals, but, happy to say our Tom is just as optimistic and energetic a young man as when he left our shelter, full of ideals; richer from the experience he had encountered, and just another one of the many people who deserve our gratitude and respect.

After this short digression, I must return to the original story, and detail the continuing events surrounding our lives.

[Tuesday, 19th September 1944]

We spent a rather disturbed second night in the shelter, half asleep, half awake, until around five o’clock we woke full of fear and dread, more shooting, which seemed to come from the direction of Oosterbeek; however, we were safe. Consequently, as we came to realize that we were so far removed from the action, we women sat in the back garden, oblivious to these events, happily peeling potatoes and preparing a meal, while the stove next to the cellar quietly ‘burbled’. We were grateful to be so far from immediate danger.

After our meal, the family “B” decided to return to their home, as it appeared that within a few days, we could normalize our lives and take up real living once again. Still, news was scarce, although we heard on the radio that the English were experiencing strong resistance and fierce counter attacks. We could not really understand this – it was so peaceful here!

Suddenly, around noon, a ‘dog-fight’, between German and British planes appeared over-head. And heavy gunfire began close by, upsetting our rather large ‘family’ of thirteen, by now, including four young children. At the same moment a Mister B. v. E. arrived on his bicycle, requesting shelter for him, his wife and two daughters. They lived on the main road to Oosterbeek, where their neighbour, a Mr. Hoefnagels had just been shot and killed by the Germans. Was this because they were afraid that we were aiding the British and this was the only solution? Our fears suddenly welled up again. Regardless, of course the B. v. E’s were welcome – they only made our ‘family’ now of seventeen! Later on, the sky, once again was festooned with parachutes, obviously to replenish the supplies of ammunition to our gallant Englishmen. However, because of the action around us (an at this point, fortunate that none of us had been hit by flying shrapnel and bullets), we had to be extremely careful while trying to retrieve the containers from under the parachutes. We did not realize at that time, how close by were the Germans, and that our lives were in their hands, or more so, in the hands of our defenders.

Around five o’clock we again returned to our shelter, but by now the electricity was cut off. The big attack was about to start – the family ‘B’ came rushing back to our shelter as well as part of the farm-house family. Our family had now grown to twenty-four, and the area of our shelter was not more than six square metres!! The noise of a heavy gun, firing constantly came to us from the direction of the farm-house, we felt threatened; for our lives, our home, and the lives of our gallant defenders. The sounds of an escalating battle came to our ears. The constant crackle of gunfire, and the bullets whistling over our refuge, gradually increased to include heavy guns. The rumble of this bombardment, and the consequent falling trees caused sand from our cellar walls and ceiling to drop on our heads. In order to distract us, and arrest our fear and dread at what was happening above us, Captain ‘B’ stared to give us a light commentary of his experiences at sea and in other lands before the war. When he had our attention, for the most part, mothers and children were holding each other tight, our breathing became gasps, as if each intake of air might be our last.

[Wednesday, 20th September 1944]

Towards morning the heavy bombardment ceased, the rifle fire was only heard between longer intervals of silence, and we were still alive! What would we find once we emerged from our hiding place? Would our house, a few metres distance, still be intact? We crept out, the men first, lead by Captain ‘B’. All seemed to be quiet, our house was intact, and even the electricity had been restored. What had happened in the world around us? We agreed that something was wrong, and while this thought was still in our heads, our disillusionment came to reality – in the person of a German soldier moving on the road. Had our fate been sealed? Had the counter attack been successful.

Mr. ‘R’ – the farmer wanted to return to his farm-house, where, as far as we knew, the English Command Post was still situated. He asked if I would accompany him, in case he encountered other Germans who just might consider him a spy! Which, in fact he would be, as his intention was to inform the commander of the situation along our road. On my return, as I rounded the corner towards our house, I saw a large party of Germans, stealthily approaching me, coming up a pathway from the Wolfhezerweg. They held their guns at the ready, pointing in my direction. I pretended to ignore them and commenced to gather some small twigs and branches along side the road, to take home for firewood. I attempted to show I was not interested in anything about me, but the job I was intent upon. My concentration was shattered when I heard a shot, and many more just behind me. As I was not dead, the shooting was not, obviously aimed at me, so I scurried home. As I rounded the corner of the house, I saw a German at the entrance to our shelter, indicating he wished to enter it to check if any English were hiding there. The mother of the two youngest children in our group (and expecting another in a couple of months), was between the door to the cellar and our enemy. It was only her courageous action, and possibly the German’s awareness of her condition, that saved our lives – as it was close to eight o’clock, our men were all in the cellar huddled around the radio awaiting the B.B.C. news at the hour. To even possess a radio in these days, would command a sentence of death. As I approached, she was saying in German: “Ach, bitte mein kinder schlafen endlich nach dieser schrecklichen Nacht. Gehen Sie bitte nicht herunter”. (“Oh, please, my children are finally asleep after the dreadful night. So, please don’t go down”.) As if hypnotized, he stopped his advance to the door. What moved this man to turn and leave this spot and continue down the road? This was just another incident to re-open our fears, what could we do? Where could we go to escape this situation in which we were ‘caught in the middle’.

Again the fighting became intense, so back to the shelter – just in time to hear, and feel, a heavy ‘crump’, so close that we feared our house had received a direct hit. When we thought it safe enough to emerge and find out, we saw that a heavy shell had landed almost on top of a shed containing fourteen rabbits, now all dead. Close by our cat was sitting calmly devouring a mouse, that had possibly been killed in the blast! ‘Such is life’.

Around noon, an alarming number of shells and bullets made it necessary to cut short our little spell of fresh air and walk around the garden. It was like a hurricane bursting above our heads and made it imperative to return to the shelter. Suddenly, we were startled by the creaking of the stairs leading down to our cellar. We were all present – who or what could it be? It was an English soldier, bare-headed, with blood on his face and hands. He could only gasp, “cigarette, water”. We gave him both, after which he returned to the surface. A few minutes later he died, his enemy must have been waiting for him, for we heard one shot. Later that evening we found his body, behind the cellar, his gun at the ready, his large blue eyes staring into infinity. A few minutes after hearing the single shot, we had a second intruder, this time a German. He appeared frightened, even ‘scared to death’/ Help or aid to the enemy would be our ruin. Our situation was precarious, to help either side could bring certain revenge from the other. Sensing our problem he left the cellar.

Hours followed, in our underground hide-away, hours of bitter suffering, and deepening fear, unbearable strain and thirst, but most of all the thirst. At any moment a soldier, enemy or friend, might enter, or toss down upon us a hand grenade. Where so many possibilities threatened to cut off our lives – these hours seemed like days. Finally there came a lull in the fighting over our heads again. One of our men decided to creep out of the shelter, and find out, if possible, the situation. Our next door neighbour’s house was ablaze, and it was apparent, a machine-gun nest had been established adjacent tour hole. As it seemed to be not too dangerous, we all decided to surface as well, only to hear the sound of many vehicles roaring along the main road. ‘Enter the gladiators – German!’ Our house seemed to be intact, but completely without glass.

Also, Many tiles had been destroyed on the roof by shrapnel and bullets. Even many branches of our trees had been hit and hung down like weeping willows. Later we learned that during this period our little hide-away had changed hands four times - English - German - English - German! The children remained quite calm, almost considering these events a game, playing war in reality. During the afternoon, more English supplies were seen being dropped - but landing in the hands of the enemy. Fortunately these supplies of ammunition were of no use to the Germans .

We stood around discussing these happenings, becoming more and more miserable with the lack of clear knowledge of what had happened, or might still happen to our area. In the midst of our discussion, the answer was given, or rather forced upon us. Advancing upon us were hordes of S.S. troops - mostly youngsters of eighteen to twenty years, playing the role of victors - juggling hand grenades and even pointing their guns directly at us. Apparently a big joke for them, but a deepening tragedy for us! They took possession of our houses, stealing anything of value, such as jewels, leather bags, silver ware, etc. Even our small store of preserves were opened and the contents splashed over walls and floors. Bottles were also opened - some, looking like wine, but containing vinegar were tasted, and in a terrible rage at their disappointment, smashed everywhere.

In a dreadful instant, we realized my son Hans was missing. After suspenseful moments, calling out to him, with no reply, he came bounding from the house, red-faced with excitement. Holding aloft a small jewel box he cried: “Mother, I have saved your beautiful ring, from grandma”. He also carried a leather bag, he had retrieved; missing its original papers, but containing a piece of cheese, our captors had planned on stealing. Delighted as I was with the return of these - I was far more delighted to have my son safely in our midst.

The Germans did not appear as if they intended to leave us, and we stood staring at them with bitterness and hatred in our hearts. One of our men asked them about the situation:- “All is safe”, was the reply, “you can sleep peacefully tonight, the English raid has been mopped-up”. As this statement was made, more and more S.S. men .filled the road. We felt as if the ‘noose’ around our necks was being ever drawn tighter. We were directly in the hands of these brutes, who appeared interested in how our large ‘family’ was fairing in our ‘camp’. Around eight o’clock in the evening, they decided to move off, allowing us to heave a sigh of relief, but still not knowing what had really happened. Had the Command Post at the farmhouse been destroyed and what of our gallant English soldiers? We were cut off from them and the water supply had been cut off from us. Our thirst was becoming unbearable, our men’s beards were growing and our food, scarcer and scarcer. As it was dangerous in the woods around us, because of possible unexploded ammunition, we had no wood for a fire and so we could not cook any food. We opened our last tin of canned meat, even realizing that to eat it would increase our thirst.

After five days and five sleepless nights, we heard the first woman’s voice outside our shelter. The voice was that of Mrs. ‘R’, the wife of our farmer friend. She had not seen or had any news of her man for three days, and had literally taken her life in her hands to come to us for any news we might have of him. At this point we could only guess - was he captured by the Germans - imprisoned - or dead? - A few minutes later we heard footsteps and a well known voice shouting “Good guy!”, and down the steps came the farmer, well-shaven and laughing, as if in answer to his wife’s concern.

The story he had to tell, was very interesting – while walking near the farm-house, three days previous, he had tried to warn an Englishman of Germans close by. As a result, he was captured by them and fortunately, instead of being shot as a spy, was locked up. After some time in custody, he decided to try and escape, and, wonder of wonders, was successful. After his escape, and to elude his captors, he roamed about, hiding, every time he heard footsteps, until he finally arrived at a bomb-shelter on the Wolfhezerweg. He remained there, allowed to share the scant rations with the occupants and even given water and a razor to shave himself.

Mrs. ‘R’, the farmer’s wife had an equally interesting story to tell. Right after her husband had left the house, the English Officers and men, manning the Command Post, were captured and taken away – to be replaced by a German Post. They occupied the house and made the life of Mrs. ‘R’ and her eldest son, pure Hell. Upon commandeering the house, they ransacked it, and after finding their food supplies, they ate some, and of what was left they had taken away, presumably for their comrades to share. After this they advised, that they were taking over the cellar for their own safety, and finally did allow her and her son to keep their mattress in small corner, but they remained virtual prisoners. On a pretext, Mrs. ‘R’ left the cellar, and eventually escaped to try and locate her husband.

As this critical situation was now resolved, and the local fighting over, at least for the present, we tried to arrange for some much needed rest and relaxation. Although we were twenty-seven in the cellar, we tried to set up a plan to give each of us a short sleep on the boys bunks. As Aunt Tine and Miss. ‘W’ were the oldest, and suffering most from lack of sleep and much tension, they were given the first chance at some good rest for three and half hours. Two of the men dared to go into the house and sleep on the floor. As we became more relaxed, our bodies began to clamour for food, so we decided to expend our last piece of cheese that we had put aside for such an emergency. It just went around, and when it was finished we again developed that terrible thirst – and no water to drink.

As necessity is the mother of invention, as the English say, the next morning we talked of a solution. As all the houses in our vicinity had only running water from the town, which had been cut off – some of the men decided to go further into the woods to try and locate an older house which might have to rely on a well and pump.

Shortly after beginning the search, one of the men returned, all smiles. He had discovered a house of the local forester, complete with a beautiful pump outside, about 1 kilometre distant. Three men went back to the well with a bicycle to transport a tub, the other carrying pails. Their return, in triumph, gave us our first water for some time. Never had a glass of fresh water tasted so refreshing!!

This almost festive occasion opened many horizons – we could now boil potatoes together with lovely clumps of endive from the gardens, even prepare a delicious apple sauce from the beautiful golden apples on our tree. The meat to complete this banquet arrived on it’s own four feet, bleating, in the form of a goat. For the first time in my life, I tasted goat meat.

As we were just concluding this wonderful meal, a wave of bombers again passed overhead. We wondered if this was heralding new landings or the arrival of Montgomery or Dempsey. Our hopes were rising once again! Almost at once we heard the rumble of heavy bombing from the direction of Arnhem.

Possibly as a result of this new attack., there came huffing, puffing, and red-faced, a Mr. “G”, who lived across from the water tower at the top of our road. He was known to all of us as a “NSB’er” -member of the Dutch Nazi Party. As was apparent, he was greatly disturbed by all the recent events, and asked what we thought of the situation and what we intended to do. Because of his political association, we remained closemouthed - wishing that he would leave. Disregarding our lack of sympathy, he continued to ramble on and obviously became more and more upset. Some of us did feel a little compassion for him, and mumbled a few words of consolation to him, but nothing more. These few words seemed to settle him and he told us he intended to flee to Scherpenzeel at once. He said that as he was in effect evacuating from the area we could take over his house, ransacking it for whatever could be of use to us. With this statement he left.

Rather doubting the whole series of events we kept watch on his home, and sure enough, a short while later we saw him leave carrying suitcase and followed by his portly wife. After a reasonable interval we went to his house and entered it. In the cellar we found many, many jars of preserved fruits, and other foods, a sack of wheat flour and another of rye flour; something we hardly remembered having existed. Jokingly we had said so long ago: “When the invasion comes we will empty the house of Mr. ‘G’, and now it had been almost literally tossed in our laps. After the food, ca me further delights with each cupboard we opened - from the swanky hats of Mrs. ‘G’ to the richly embroidered lounging jackets of her husband. We felt as exuberant as a bunch of school children on the last day of the term.

The noise of fearsome fighting had died away in Oosterbeek, and left us wondering about the burghers of the town. Were they in the most part safe? Had they been evacuated? Only after two more days of wondering; did we find out how the situation was. Forced evacuation was t hen announced and the people of the town streamed away.

A local doctor from the Red Cross, in keeping with their traditions, was concerned that everyone was advised, and able to evacuate. Possibly there were ill or wounded who could not move. In the course of this humanitarian patrol, he discovered our little community, and could hardly believe our tales of living almost like nomads on our small street. The bearded faces of our men, the pale haggard faces of the women, bore out our stories of the life we had been leading. He was impressed with the ways we had coped with unbelievable situations – ten days and nights without proper food, water and proper rest and sleep. Because of the water supply being cut off, all aspects of hygiene were lacking. The tales of organizing the meagre food supplies that we managed to garner also seemed to impress him, so that he said: “Let us, from now on, struggle through this dreadful period together”.

In view of this remark, we put forward our greatest concern - how to get more food. In Ede, he said, was a Red Cross food distribution post. So a party of six of our men set out on their bikes, across the heath to collect the necessary rations. It was agreed to return the supplies to the doctor’s home (only one kilometre away) for distribution.

We were elated with the huge amounts of butter, cheese and other staples as well as small amount of milk. Like wolves we attacked it – it tasted like a real feast!

After that first, visit of Dr. ‘C’, further occasions followed, and it was a big sensation when the Red Cross vehicle, with the white flag flying, stopped in front of our door with food and news. It was in this manner, now our radio could not function, that we learned of the pending Polish part of the overall manoeuvre, and the para-drop at the Driel ferry point, as well as other pieces of news of the surrounding war scene; we believed it all - for what else could we do? We understood that bridgeheads had been established at Kleef, Emmerich and Keulen , as well as at Wageningen, Rhenen and Amerongen in Holland – what terrific good news!! No it was not necessary to evacuate - perhaps only a few more days and then we would be free! Once again our hope soared, and our confidence returned.

Unfortunately, even with this welcome change in events, we were forced to evacuate our Jewish Miss. ‘W’. On a beautiful morning, once again we had to swiftly dive into our cellar for shelter. Crowds of aeroplanes were flying over our heads, heavy anti-aircraft fire burst began falling around us, and the sudden return to the present danger was too much for the nerves of Miss. ‘W’ and she began to suffer a serious break-down. Our Dr. Corthuis advised her immediate evacuation from the area, and she was collected by the Red Cross car - we never heard of her again.

Possibly, some of her concerns, came from the fact that we were in the middle of the battlefield and so many dead soldiers lay all around us. As a result of the easing of the fighting some of our men decided to organize a burial detail.

It was now 30th of September, and on that still , sombre morning, with scattered clouds above, it reminded us of the disorganized, broken pattern of our lives . Our men left in the occasional rain-showers, armed with spades and picks to find a more peaceful place to bury the remains of our gallant - would be - rescuers. It was a sad procession, and their participation in the necessary function left a dark blot on our souls that all of time can never erase. Captain Blaauw, standing above the open graves, beneath the evergreen pine-trees, remembered in silent prayer, the resolve and unyielding courage of these young men, who had given their lives, attempting to change ours. He tried to commemorate these thoughts back across the miles to England, to the families, waiting in vain for some words from their sons, lovers, husbands and fathers.

Later the same day we heard that the great land Army was really approaching - only some 10 kilometres from s’Hertogenbosch. this news seemed punctuated by the roar of planes overhead, and, we thought, heralded new landings, and may be deciding our fate in the next few days. We learned that the English Army had been repulsed at Pannerden, south west of Arnhem, and the Poles had been surrounded near Wageningen. These reports dampened our enthusiasm, but the fact that the main army force was near s’Hertogenbosch, heightened our hopes that our liberation was imminent.

At this point we came to realize that our food supply had been rapidly diminishing and must, if possible, be replenished. Our patrol of the strong - and the brave - who in the past had journeyed to Ede to bring us bread, was ready to again attempt to find us food. They returned with kilos of horse meat.

On their return, Fieb Begram van Eeten was frightened by a grenade exploding near by, and in her panic, jumped through a window in a house which was close by. In trying to save herself, she suffered a terrible gash in her head, which needed immediate medical attention. This case plus other injuries of Piet Rossenberg and my Hans to their hands and knees while wood cutting, decided us to make up a party of the wounded and find our way to the home of Dr. Oorthuis. As we approached his house, we were hurried on our way by a virtual rain of exploding, whistling grenades. We charged into the house, continuing straight to the cellar! All of us surprised as to the origin of this latest onslaught; after half an hour, all seemed quiet again. The doctor dressed and bandaged the wounded and then decided to accompany us on our return. These alternating periods of silence and explosions seemed an ever threatening pressure on our ordinary lives – eating, sleeping and conducting our daily tasks. These pressures affect us in different ways, and we were grateful to Dr. O. for returning with us. Aunt tine, our guest, was close to exhaustion and the doctor recommended her immediate transfer to a hospital – but the nearest one was 10 kilometres from here and we had no auto for transportation! Mr. Rossenberg and Uncle Jo decided to take her and her luggage, by bicycle to the outskirts of Ede where she had relatives. On arrival there, they found no one at home, and the house locked up. Friendly neighbours offered to take her in till their return – and a few days later, she was transported by a farmers wagon to hospital.We learned later that her condition was very bad – not only was she completley exhausted psychologically, but she was suffering from anaemia. She was required to stay for the next nine months in the hospital, but I am happy to report she recovered totally and at the end of the war, she resumed her profession as a chemist in Amsterdam.

Captan Blaauw often made lonely forays into the village, ostensibly to check his personal belongings at his badly damaged room in the boarding house there. Our curiousity was richly rewarded on day when he returned, towing along beside his bicycle, tethered by a knotted handkerchief, a goat!! The poor animal had been walking, wailing through the village, and apparently its hunger and thirst had prompted it to give in to, and trust the captain. Upon their arrival at our house, we were delighted with the promise of fresh milk that ‘she’ gave us. But who was going to milk her? Of course our farmer, Mr. Rossenberg, knew how to accomplish the chore, and shortly the little ones had their first cups of fresh milk in some time. After a few days, we mixed together a litre of milk with three litres of water and some substitute extract – what a delicious cup of coffee! The mysteries of Captain Blaauw continued; what did he collect so often from his damaged boarding house? We dared not question him, and he never offered to disclose to us his reasons. Only much later the great secret would be revealed to us.

The nights were becoming much quieter; the garnering of supplies of food and water became our greatest worries, keeping us fairly busy all day. As the month of October began, it started turning colder with more rain, our shelter became damp and less bearable. There was not much news coming from outside the perimeter of our battlegrounds. Occasionally we would hear from the main road, the sounds of German columns marching by. All “liveable” houses had been requisitioned; even Mrs. Blaauw had been given notice to billet troops. The noose was again becoming a bit tighter. One evening, to escape the dampness and the cold of our shelter, we came into our house and all 27 of us were sitting on the floor of the parlour, surrounding our only illumination, a fluttering Christmas candle. Suddenly, through the window opening protected by only a piece of cardboard, we heard German voices. Our neighbour, Mr Korporaal, with a few other men, went outside to enquire “was ist los?” (What is up?) the answer – billeting for 24 soldiers for one night or longer. Another tightening of the noose.

Mr Korporaal, who had slowly but surely become our camp leader, for his knowledge of “their” language as well as a gift for gentle but firm persuasion, explained our already strained position to their leader. He pretended that as all windows were gone in the house and that the cardboard over the parlour openings was our only protection against the elements for 27 people. This Story gained for our neighbour – and consequently for us – a victory. Many times, acting as our official leader, his intelligent arguments won over the most difficult deadlocks. The next day, again he had to carry our cause against a fresh billeting, and did so, so favourably that, the same evening the Germans sent us a huge bucket of hot chicken soup!! Even with this gesture of good will from our local captors, we felt our continued residence here, hung on a fine thread – one more tug at the string and we would fall into the hands of a few tyrannical villains, like Hitler etc. Each day, now, we carried on discussions as to how best to escape from the situation that surrounded us. We did not know in which direction it would be safest to move. The village was empty, Captain B. had stopped his mysterious trips there, but the sounds of heavy shelling came from the direction of the Betuwe, south of the river.

One afternoon, four of us decided to search through the woods for whatever could be found of value to our existence. Wim Thieme, Marion Begram v. E., my son Hans and I, after about ten minutes began finding all manner of things, shaving soap, razor blades, socks, tea, oatmeal, tinned meats etc. A bit farther away, we even found two new uniform tunics. We came to realise that we had garnered far more than we could reasonably carry, and decided to create a cache of the excess, at a spot where we could retrieve it later. Just as we had finished this job, and Hans and Mr. Thieme had gone on ahead, we were startled by the crash of an exploding shell, followed by the dropping of several branches – fooled by a sinister silence. Then more shells came towards us, we had to seek shelter, but where? Hans and Mr. T. were well ahead of us, and Marion and I remained behind, desperately waiting – for what? Again another rain of splinters and we started to run, in fear, with our hands over our ears. Marion was screaming, and I was frantically calling for my Hans, but with never a reply. In our flight, Marion had lost a shoe, and she arrived with me limping badly, at the door to a woodsman’s hut. We managed to get inside, but were still desperate to find signs of the other two. The firing continued with intervals of a few seconds; we learned that the shelling ws coming from the Betuwe south of the river and aimed at the hotel de Bilderberg, only a few minutes distance from us. (We later heard a secret S.S. camp was situated there.) Finally the shelling ceased and we took the risk of leaving our uncomfortable position under some boards on the floor and started searching again for Hans and Mr. T.. Calling and shouting, we moved in the direction we hoped to find at least some evidence of them. At last, after a long, long, time, there was a reply, form an entirely different direction; the voice of my child! How great was my happiness after all the sombre, dire thoughts that had gone through my head. Once again, it proved the old Dutch saying “People often suffer most, by fear of suffering, that they never have to endure – in this way, they carry more than God gives them to bear”. Hans and Mr. T. had been able to take shelter in the crater from a previous bomb or shell, waiting while the current rain of explosives flew over their heads. For the umpteenth time. We had been saved again!

After having survived this trip, we decided to postpone any further quests for whatever useful objects we could find. Before completely recovering from this shock we were dealt a more fearful blow.

A nephew of the Rossenberg’s who had literally taken his life in his hands, had bicycled all the way from Utrecht, to learn what he could of the situation of his aunt, uncle and children, not knowing if they were dead or alive. After the reunion was established, he and the Rossenberg’s oldest son, Gerard, decided to conduct their own foray into the woods to see what they might find that could be of use. Only after many hours, did we suddenly miss them. In the middle of a lively discussion with the Rossenbergs as to how best to start a search for them, six S.S. men marched through our gate, enquiring who was the father of Gerard Rossenberg. An extremely official interrogation followed, of course, with all of us grouped around, and hearing one of the Germans say, with a satanic sneer “That one (Gerard) you are not going to see return for a long time!” He further enquired of the age and profession of the boys. Gerard had reached the possibly fatal age of 19 years and thus was liable for deportation to a German forced labour camp. He then stated that they were suspected of spying, as, around the Hotel de Bilderberg, they had been taking a good look a the guns surrounding the building, as well as collecting many papers and maps that had been discarded by the British. Upon their arrest, the S.S. told us, they had been sent to a prison, and whatever their fate might be, no one could tell. With these statements, the tyrannical “sons of Hitler” marched off, leaving behind our group, especially the parents and relations, in a state of powerless panic. Powerless we all were – because of living in complete isolation, - not knowing anything of “headquarters” or a German police station or area of authority to whom we could turn for advice or information. While we were pondering the fate of the boys and any possible intercession the guns from the Betuwe began rumbling again and shells were falling not more than 100 meters away. This action pinned us down, virtually till curfew time 6 O’clock and stalled any action we might have taken this day to save the boys. After a sleepless night and much discussion of possibilities, Captain B. came up with the right suggestion. In the morning, as there was not any more shelling from the Betuwe, he would contact one of the local officers in the neighbourhood. He learned that indeed S.S. Headquarters were at the Bilderberg, and so in company with Mr Rossenberg, they went there. Upon entering they found the main floor completely deserted, and then realised that because of the heavy shelling, the only activity was carried on in the basement. Their trip turned out to be totally unprofitable – no one could, or would, render any information that could be of any use. It probably eased the continuing concern, not to be aware that the day was rapidly approaching when we would all be driven into exile from our community. It was now 18th October 1944.

The next morning, Mr. Rossenberg made expeditions in all directions trying to locate, or find nay news of his son, who certainly would not be walking around in the meadows surrounding the Bilderberg! What else could be expected of a distraught father? Providence provided a distraction from his worries, in the form of a wounded cow. It had been wounded in two spots, presumably a victim of the previous day’s shelling. He decided to lead it to our place before making up his mind about its fate – after all it could represent many a meal for our group. After some discussion, old Grandfather Korporaal suggested the courageous plan to slaughter it. This was quite an undertaking because of the critical situation we were in - for within an hour we might be given orders to evacuate the area. At the same time, it would be inhumane to leave the poor animal in its present condition. Dr. O. who happened by the Red Cross car at this moment, also concurred in the killing of the poor beast. Even if he could dress its wounds, where could be obtain food for it? Thus the decision was taken for the good of the suffering animal – but also for preservation of our group.

Now the decision had been taken, how best to accomplish it? Dr. O. decided to ask one of the German soldiers billeted at the house of one of our neighbours to shoot the animal, to which of course, he happily complied. Using a revolver to him was no different than for us to use a soup ladle. Now – to work! The old Daniels couple were conducting the butchering and meekly we followed their orders. Thus a new period started in our existence, days of feverish activity. Even Mr. Rossenberg joined in the heavy work, he hacked off the skin, divided the carcass, and as we slowly stripped the meat from the bones, he turned the meat grinder as if his life depended upon it! Somehow, we all sensed a change, a few more days or hours and we would be driven away to yet unknown places. Thanks to all the hustle and bustle, we had little time to reflect on it. An almost endless amount of minced-meat balls, rump steaks, etc., were prepared over three roaring stoves in the garden as it was quiet in the sky overhead. We were living in good harmony, sharing each other’s lot, trying to help keep each other on their feet, refusing to give way to despair. Each had his own suggestions concerning the meat; re salting, cooking, roasting, marinating. We did a bit of everything and consequently, came to a wide assortment. My husband, a vegetarian, felt more and more ill at this apparent glut of meat, and almost stopped eating altogether.

On the next day, a sunny Sunday morning, we received our sentences: “Evacuation within two hours”. It was at that moment 11.00 am on 22nd October 1944.

So now we knew when we must go – in two hours we must leave what we had thought to be our safe hide-out, without transport and without definite destination, the when, but not the where! It seemed like an adventure out of a book, we had no time for brooding. In unity, we decided to conceal our most valuable possessions in a brick-lined area underground, close to our own shelter, but where earlier we had been hiding some Jewish refugees. Afterwards, it could be made almost invisible – but – no big parcels, just a few valuables, such as silverware, some precious porcelain, stamp albums and a few summer clothes. We were swarming around like ants, doing our utmost to prepare to take away or stow away just the right things, or leave them to the ravages of the Germans intending occupation of our homes.

We started preparing a meal of meatballs, surprised at remaining in such a happy mood. Meanwhile, one of our two hours had gone by and we set to deciding on a plan of destinations. Each of us would take one bicycle – a two wheeled transport, fully packed, plus one large handcart, that we had “liberated” for the occasion, loaded down with blankets and mattresses etc., which would be pushed in turn. The family Rossenberg, still with no news of their son and their nephew, decided to travel by bicycle and try and reach relations at Bunnik, in the direction of Utrecht, and the family Thieme would travel to Ede with their three children. That way, there were fourteen of us left: Captain Blaauw and his sister-in-law, the family Korporaal (4 people), the family Begram v. E. (4 persons), my husband and I, with the two young sons. Around three o’clock, our caravan started to move off – a sober procession, all of us with fear in our hearts as to how and when, if ever, we would see our beloved refuge again. At the gate, a heavily armed German wearing a scowling face, was seeing us off.

Mrs B.v.E. insisted on taking her old pram with her. This object as well as our milk goat, and another goat that had wandered to us, gave a special accent to our procession, as we travelled along the long, quiet road to Wolfheze. We must have appeared as a funeral procession, slowly advancing towards that village, but still we were wary of anti-aircraft shells buzzing over our heads.

When we reached the railway crossing in Wolfheze, we decided on a moments rest, but were refused the possibility by a German, who came rushing from the station, forbidding us from “loitering”. A few hundred meters along the road, it became almost impossible for our cart between the shell-holes. Captain B. with an application of seamanship, and ropes taut in a united effort, managed the miracle of piloting us through, and on the move again. Now, on both sides of the road, we saw the deserted gliders, fragments of aeroplanes and much discarded or damaged material from the Tommie’s recent air operation. As a result of our delay in navigating the shell-pocked road, we came to realise that we would not be able to reach our goal for the night; Schaarsbergen. At the next intersection of our route, was a large farmhouse and we decided to enquire as to whether we might spend the night there. Our caravan finally arrived at the spot at 7.30pm and from the road, the farm seemed deserted, and no one had the courage to enter the large yard and ask for shelter. Our brave leader Mr. Korporaal boldly came forward, opened the gate and marched in. Great was our consternation, when suddenly, a number of uniformed men came dashing from the house. Apparently the farm had been requisitioned by the Germans and, like us, the occupants driven away. We remained, milling around the gate, worried as to what we must do if Mr. K returned with negative news. The children, oblivious of the seriousness of our quandary, started playing hide and seek in the adjacent half dark, oak coppice – we passed the time munching a few meat balls from our supplies. After a good fifteen minutes, Mr. K. returned, smiling, between two officers, to tell us that we had been given permission to sleep for one night in the hay loft. We drove our caravan through the gate, and groped our way around the yard, in the dark, to our “lodgings” Gratefully, we climbed the big ladder to our “digs”. And although we were pretty exhausted, started happily digging holes in the hay, as if we had always bedded down in this manner. Gradually one by one, we fell asleep, bothered by voices in the yard, the clatter of hooves in the barn and shooting in the distance. At day-break, we were startled and rudely awakened by the voice of Captain B. shouting an agonising “ow”. He had been rudely awakened by jamming his toe on a stray hayfork. A new day of life was starting, and what a life! What kind of a day would it be? We jumped from our “beds”, sliding down from the pile of hay, and with stiff limbs, descending the ladder. My children, Hans and Joop, were having wonderful fun, but for us grown-ups, it was cold, wet and sombre. Having been driven from our homes and with little prospect of reaching a safe haven, this day or in the near future. In the yard we found ourselves among many, many Germans. Our shower was the pump by the house. The men took off their coats and shirts, washing their heads under the gush of water from the pump. We were rather more modest, washing hands and face with our rationed, excuse for soap. Even with this poor soap, we indeed felt better able to face the day. A kind German passed among us with a trolley containing huge jugs of coffee and he offered us a hot drink. We quickly produced mugs, (picked up in our woods after the English paratroops had gone by) and with this “normal” start to the day, suddenly, life did not seem so bad at all. At that moment we did not stop to realise we were accepting favours from the enemy.

Our breakfast consisted of watery oatmeal porridge, with no milk or sugar on it, cooked on a little camp stove which we fired with bits of wood. Immediately after the meal, we had to pack on move on, as we had been ordered by our “hosts” in gruff, commanding terms. Captain B. was shivering with the cold and looked deathly pale; the hayfork prick did really hurt him. Mrs B.v.E. also did not feel well, and there was no place where we might find shelter from the steadily drizzling rain. The only thing was for us to trudge on, and eventually at the Amsterdam road, we came upon a road side shack that had formerly been a shelter for road workers to give a roof over their heads during bad weather.

We tethered our goats to graze, and the fourteen of us settled down on the mattresses taken from our hand cart; although they were pretty wet, they still offered us a bit of relaxation. As it turned towards evening, the local train to Ede roared by in close proximity, jarring us from our lethargy. Supper time – we opened a few jars of preserved fruit and in combination with the eternal meatballs, gave us a meal that at the time, tasted like the most expensive dinner we could remember in peace time.

However, our supplies were rapidly coming to an end, we had no heating, no material to stoke our camp stove or even matches to light the fire. One morning, with a few others, including of course the children, we decide on a fast return trip on our bicycles to the Zonneheuvelweg to see if we might salvage a few more articles. The Germans had taken complete possession of our houses, but, thank god, they were reasonably friendly and gave us permission to pick up a few extra things, (of course keeping a watchful eye on what we did.) they had installed a telephone, and on arrival, they were washing the floor with one of my nicest woollen dresses! The beds had been moved, and everything in the house appeared upside down. Whatever furniture they could not use, was all put outside in the rain. Hans was sad because he had to leave his cat behind, and Joop wanted to take with him all sorts of toys, but there was no room to transport them on our bikes. So, with what was a reasonable load, we returned to our temporary shack.

The number of “live-stock” was steadily increasing; we now had three goats, thirteen chickens and two dogs. In each case, we were given the extra animals by the original owners who were not able to take all of them with them when ordered to evacuate their homes. We, as community still remained together. Later, many persons were envious of this. At the time, we did not realise that the life we were struggling through together was the basis for a commune, a type of living unknown then in Holland. We had all known the feelings of danger and hunger from time to time, but still we shared everything and were always ready to help the others, with my boys Hans and Joop, the only children.

After our return to our temporary “home” and upon surveying our situation and provisions, we concluded that we could not continue much longer in this manner. My careful, faithful Johan decided to go on his bike to Otterlo, some twenty kilometres away, and which was the site of the Kroller-Muller art museum. The director, a Mr. Auping, was well known to my husband, in connection with Johan’s profession as a painter, and who just two months before had agreed to store Johan’s portraits of his mother and father. During their meeting, Mr Auping gave Johan a letter of introduction to a certain Mr. Pluim, who was in charge of evacuation arrangements in Harskamp and surroundings. It was via this Mr. Pluim, a café proprietor in Harskamp, that Johan received the address of a farm house at Westeneng, close to Wekerom and Harskamp, so far containing no other evacuees. We learned the reason for this state of affairs on arrival thee that evening! The farm was occupied by two stiff, miserly brothers, who in the past, stubbornly refused any “guests” and met us with grumbling and growling. The farmhouse was quite old, and the two brothers slept together in a quaint old cupboard-bed. With a cask of salted meat in front of it, standing next to the chamber-pot. A fat old mongrel was used to sleeping between the two men – it was altogether a dirty mess. As in the past, we were not allowed to stay in their house; (under the filthy circumstances, this did not hurt our feelings.) We were first assigned to their empty hen house, but after much discussion, they allowed us to use their hay loft, above the cows in the barn. Here, we could lay out all our mattresses and sleep in a long row of fourteen persons. This turned out to be our home for the next nine months, and strange as this may sound, a pleasant time started with this settling in and continued to the end.

Possibly our “host’s” attitude towards any “roomers” was that they would be expected to share food as well as a “roof”. In our case, this gave them no problems at all. On our way to the farm, we had plundered an abandoned food shop, and consequently, had enough food for the coming days. Some people in a Red Cross car had assisted us in looting the store, offering the philosophy that it was a question of our survival or leaving it all to the Germans. Thus their permission to plunder, which also took in the fact that four of our men, literally in hiding from the German T.O.D. could obviously not request food coupons – or take the chance of this organisation picking them up and deporting them to a German labour camp.

We installed our stove in the abandoned hen house along with some big kettles. These we had “organised” from a deserted boarding school. In there, we cooked our daily rye porridge as well as our “one pan” meals, usually consisting of “liberated” potatoes, turnips or cabbage – alternated by potatoes and our ever available preserved meat balls or for a change, pieces of salted meat. This diet seemed good for all of us but my poor Johan. Possibly because he still maintained his principles as a vegetarian, he became more and more ill, starting to have a fever and looked gaunt and a bad colour. It was a period of great anxiety for both Johan and me, till we eventually consulted Dr. Breebaart, originally from Arnhem, but like us all, evacuated to our area. His diagnosis – jaundice from possibly some liver trouble, with the prescribed therapy, buttermilk (which he loathed), all food with no fat, which meant no eggs. Eggs were a large part of his diet as we daily we able to “pinch” many, right form under the chickens. This was the main chore for the children, waiting for signs of a chicken being about to lay an egg – then carefully taking it from under the hen and dashing in triumph to the hen house – our kitchen! (How is it possible that our children have not turned into fully fledged thieves?) at the suggestion of Dr. Breebaart, that Johan should have some X-rays taken, he rode his bicycle (with wooden tyres) to the KKroller Muller Museum, where a Rontgen apparatus was available. The results of these pictures were encouraging – no physical problems were apparent, possibly only a problem of diet. This good news made the happiness of both of us so complete, that we almost felt we were in Paradise. Slowly his condition improved and once again he was allowed to participate in our “normal” diet of porridge, rye bread with “borrowed” cheese. This and the approaching spring, and love took care of the rest!

In this way, our lives would continue for the next nine months – it seemed so peaceful, no longer did one hear the unbearable thunder of the big guns and the “whomp” of the exploding shells and flying splinters. There were no Germans billeted nearby, only the occasional German inspection patrols, looking for young men to requisition and/or bacon, meat and milk. Except for the odd aeroplane overhead, we almost felt free! – free to move around once again. The family B.v.E. left on their bikes to stay with relatives at Utrecht, Captain B.’s sister-in-law located another farm house where she could live on her own. These movements reduced our company to just 9 people, and with less hungry stomachs to fill, the quality and quantity of the prepared portions was rising. The preparation of the food still took up most of the days (as there were only two of us women now available). And the other major chore was sawing the wood, for the stove, which we “organised” the previous night. Hans began working for a nearby farmer and receiving full-board, and we became almost envious of him – as much “real” porridge as he wanted complete meals of fresh meat and vegetables and often pancakes at the end of the day! Sometimes he returned in the evenings with a crumpled piece of pancake tucked in his shirt as a treat for his young brother. There were nice friends – playmates for the boys, who lived at the surrounding farms. At our farm there was no woman and so the two brothers handled everything, even to cooking their monotonous one pan meals.

Over the last few months our relations with them steadily improved, and after seven o’clock each evening, we were allowed to sit in their room – finally to be able to sit on a real chair and we spent that time telling each other stories or playing games of riddles or other questing type games such as guessing the name of an object that one of us would select from within the room. They even took to joining us for our daily cup of hot milk “borrowed” silently from their own cows!! With the children being so close to all these animals during breeding and calving, I feel they learned the basics of life, not normally experienced by youngsters raised in a “city” environment. The birth of a calf or a goat came almost to be a festival occasion.

Just the same, daily life was not always festive; there were often tense moments as well. Especially during January and February, we could expect, during any given night, a surprise raid by the “enemy”. For example, in the middle of one night, six armed Germans came knocking loudly on the door to the area below our hay loft. As usual, they were looking for English soldiers, Jews, or others who may be hiding for one reason or another. Upon hearing the knocking, our five younger men immediately crawled to a previously prepared area under the hay, made ready for just such an emergency. Their still warm mattresses were dragged by we two women with Captain B., in front of the open window to cool down, there being a heavy frost that night. When the Germans came up the ladder to the loft, our hearts were in our mouths, especially when they began feeling those mattresses, and enquiring who they belonged to. A reasonable answer to such a question was also prepared before hand – “They belong to other evacuees who have just departed to visit relatives”. Later on, they carry on sporadic raids in day-time, when we were in the hen house, cooking or preparing meals. At these times, the men would hide in the surrounding ditches or hollows – sometimes for most of the daylight hours, so we would carry their hot meal and something to drink, to them, as there was always the threat of discovery and arrest.

In spite of these frequent disturbances or our peace, we remained together in close harmony – we were young and full of pleasant illusions. Also, Captain B., at the age of 68, bachelor and retired sea captain was our continual entertainer – with his wealth of amusing travel experiences and day-to-day plans. For example, one of his plans involved cutting thin pieces of wood from a small fir tree, which he then had Johan paint black and white, together with a black and white squared board. We now had a set of draughts, with which Captain B. organised a competition, and for weeks we played draughts like mad, to finally arrive at the championship. The winner? Captain B.! As well, during December, the headmaster of the school at Wekerom offered to teach Hans some of the schooling that he was missing in our present circumstances, and we all joined in with his homework. It was fun for us, and was also beneficial to Hans’ general education.

Towards the middle of April, a group of Germans occupied the farmhouse, leaving us to our hay loft and hen house. They arrived I horse drawn-auto’s, an on the whole, came over as a tired, hungry, neglected gang, who were plundering the farmhouses for food. Fortunately for us, they did not remain long; on April 16th, an orderly arrived and within 10 minutes they all departed. Now we were certain – liberation was approaching!

During the night, we were kept awake by the distant roar of heavy guns and sporadic shooting. At six o’clock the next morning, on April 17th, we saw a farmhouse in the direction of Otterlo on fire. With great haste, we collected our clothes and bicycles and hid them all in ditches and hollows. At 10 o’clock a group of Germans, without helmets, obviously on the run, rushed into the farm yard looking for bicycles. The only one in evidence was Jopie’s child’s bike, which was decided was better than nothing and off they flew!! Those were the last Germans in uniform we were to see!

Jopie reacted very well to his loss, he just said “Oh, the English are going to give me a new bike!”

Two hours later, at noon of the seventeenth, we saw the first Canadian tanks advancing into Wekerom. That afternoon, we were eating chocolate and smoking Canadian cigarettes!! For the second time we had been liberated – would this time be permanent? Captain B. had carried with him a Dutch flag which he now pulled up the hen house and decorating every spot around it with orange sashes that we also had brought with us. We were drinking English tea and feeling tipsy with happiness!!

A large number of Canadians bivouacked next to our farmhouse, and that bleak site became the centre of joy to us. Hans was immediately taken on as a cook’s helper and brought us from time to time the most delicious bits and pieces. Jopie came to us with hands full of sweets, such as dried apricots and raisins. All day we were surrounded by the sound of a radio… after five years! It was one big party. Apparently it happened to be a kind of headquarters for troops in the area. We had recently sowed some radishes and we offered our first ones to the Major. It was a little “bait” that resulted in his invitation to join them in a beautiful dinner. Everything was delicious. We two ladies – Truus and I – had preened ourselves for the occasion. With a new piece of REAL Canadian soap, we washed our hair and donned our one and only dress that we carried along with us on our trek for just such an occasion. We felt like queens of the ball – which also caused some difficult moments!

The Canadians remained for a few weeks. During the evenings, there were often open-air pictures, and day after day these unsurpassed, delicious bits of food; we could not get enough of it, after months of mostly rye-porridge without sugar and salt.

On the 5th May, all of Holland was liberated and we heard on the radio, of the capitulation, our elation rose to great heights. Bonfires were lit in celebration – all pressure and tension “went up in smoke” with the fires.

But returning to Oosterbeek was still out of the question. Apparently 80 percent of the village had been destroyed. Our houses – would they still be there? Wild rumours were passed around – such as that huge numbers of mines were planted all about the Bilderberg area. Finally, fter waiting and waiting, Zonneheuvelweg 16 and 18 received “residence permit” for one day. Captain b., Mr. and Mrs. Korporaal and I, went back to our “homes”, while Johan remained with the boys. As we arrived on our road, we found that nothing had been cleared yet, fallen trees and branches across the road, bricks and all sorts of rubble from the destroyed water tower at the top of the road and much old war material. The houses were still standing, but as we carefully entered them, the sight brought tears to ur eyes. No single piece of furniture was recognisable; strange bits of household goods, with the only few chairs that had belonged to us, standing outside, open to the weather and completely ruined by the rains. However, more important to us, was to find if our buried and valuable possessions were still intact. In suspense Mr. K. removed the soil until his spade struck something hard – we worried that it might be a mine – but it was a piece of root of a bush that we had planted over our cache to camouflage the spot, before we departed. He went on digging until he reached the area of our hoard. Everything appeared untouched, nothing had been discovered and the most important of our possessions had been saved.

We then decided to start to put our house in order – it was difficult to know where to start – it would take weeks to complete, and we had to do it all ourselves, as no outside help was possible at this period. On the second day of June 1945 we returned with the rest of our worldly possessions by horse and wagon. Thanks to Johan, the broken windows had been closed with plastic till better materials became available, and we are building up again!

The boys have returned to school and Johan has received permission to paint in the destroyed city of Arnhem. We don’t as yet have a residence permit to live in our own house, as all dwellings must be approved as safe before we can legally return, so we live here clandestinely till then. Captain. ‘B’ has been invited to come and stay with us, as his old boarding house was destroyed by fire.

On the 25th of July, the Reverend Oskamp, a pastor in Velp has offered to confirm our marriage and a totally new life will commence.

Miep Mekkink.

The foregoing was originally written in Dutch by Mrs. W.M.L. Mekkink van den Brink, from the day to day diary she kept of that fateful period from 17 September 1944 up to the final liberation of her country – and her return to Zonneheuvelweg 16, where she and her husband Johan resided till the end of 1981, when they moved closer to the centre of Oosterbeek.

In the translation of this chronicle we have tried to retain the pure essence of the pathos and day to day frustrations and fears of this hardy and resilient Dutch group; it could almost be considered a cross section of the Dutch nation that endured the war years. As we currently reside at Zonneheuvelweg 16, the period of translating, with very little imagination, gave us the feeling of being with these wonderful people.

One or two happenings may have left questions to the reader.

First, we are happy to relate, the young Gerard Rossenberg and his cousin returned at the end of the war, unharmed, from their German confinement.

Secondly, there were the mysterious trips of Kapitein. Blaauw to Oosterbeek.

The whole of this answer could make a complete story of it’s own. As indicated in the original story, he was a retired sea-captain, who had decided to live the rest of his life in The Hague. At the start of 1943, he, along with many others, was ordered to evacuate The Hague, for security reasons as well as to provide more billets for the German forces placed there. He decided to move to what at that time was a more tranquil area of his homeland – Oosterbeek, and also where a brother resided.

Here he took up lodgings with a family Aufenacker on the Pietersbergseweg. The man of the house, who worked for a bank in Amsterdam, was, under German supervision, a courier carrying confiscated Jewish money and valuables all the way to Brussels. At a certain time in September 1944 his trip to Brussels was blocked and he found he could not even return to Amsterdam. He finally decided to store the steel case, which contained some one million guilders of personal effects, stock certificates and promissory notes belonging to Jewish families, in the cellar of his home. Almost immediately the area including Pietersbergseweg was involved in the battle of the British Airborne’s and among others the Aufneckers evacuated the area – possibly to Germany?

On his – Kapitain Blaauw’s first return to his lodgings from the Zonneheuvelweg, his main concern was the case of valuables in the cellar. The case was intact, and he decided then to ‘organise’ the contents for possible future return to the rightful owners. Because of the size and weight of the case, it necessitated the removal of the contents ‘bit by bit’ all the way to his sister-in-law’s house on the Zonneheuvelweg, where he buried them in the presence of his brother’s wife. This was the reason for his mysterious trips back and forth from the relative safety of the shelter to his lodgings.

The end of the story is, that after the liberation, he recovered this treasure and turned it over to the Dutch Government, in the hope that it might possibly be returned to the original Jewish owners if they survived.

After living with the family Mekkink at Zonneheuvelweg 16 until 1954, he then moved back again to his residence in The Hague, where he passed away that same year, at the age of 76.

Mieke Honcoop & Eric Robbins.

NOTES.

[1] See also account by Capt. C.A. Simmons. 181 Airlanding Field Ambulance, R.A.M.C.

Source:

Kindly supplied by R Hilton

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.