Just after midnight on February 28, 1942, 120 men dropped into the snow-covered fields surrounding the village of Bruneval in France. Less than 3 hours later, they scrambled down the cliffs to escape with a stolen German radar and two captured technicians, having lost only a handful of men. The audacity and precision with which the operation was conducted quickly became the stuff of legend. The Bruneval raid, which bolstered the morale of a nation under siege, became the Parachute Regiment’s first battle honour.

Planning

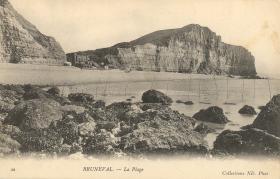

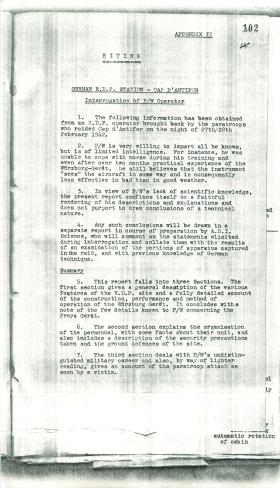

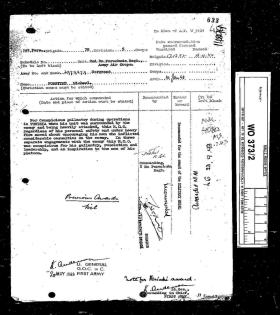

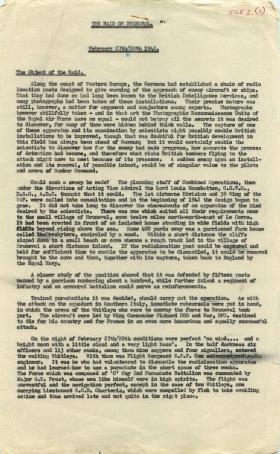

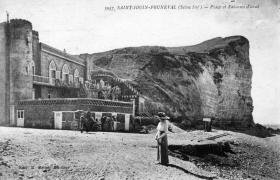

On January 8, 1942, Admiral Lord Mountbatten, the Chief of Combined Operations, contacted the Headquarters of the 1st Airborne Division and the RAF's 38 Wing to secure their support for a raid on a radar station near the village of Bruneval. The station was situated on a clifftop twelve miles north of Le Havre, and had been recently spotted on December 5, 1941, by a Spitfire of the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU) flown by Flight Lieutenant Tony Hill. Although Hill was detected and his presence relayed to Luftwaffe Command in Le Havre, he returned home with a clear photo of a large black bowl which was of interest to Air Intelligence. This was to be the raid's target.

Little was known about the equipment used at Bruneval, but RAF Bomber Command strongly suspected that it was helping the Germans inflict heavy losses on their aircraft. At that time, four out of every hundred bombers sent into German-occupied territory were being lost. Having already discovered the Freya radar, Dr Reginald Jones of Air Intelligence now suspected that the Germans were using another unit, later revealed to be the Würzburg radar, which had shorter range but better precision. This was the black bowl which could be seen clearly in Tony Hill's picture, and which Dr Jones now wanted to study. However, as there was a special interest in recovering the Würzburg before it could be destroyed, a slow assault from the sea had to be ruled out. Jones' request was passed on to Mountbatten and the planners at Combined Operations Headquarters at Loch Fyne in Scotland, who decided that an airborne assault was the safest way to retrieve the radar intact. Lieutenant General Browning agreed, and the regiment's history later noted "a successful operation at this stage would be excellent as an incentive to the troops and as a demonstration of their value". It was decided that training could be completed by the end of February, when a full moon would make the visibility perfect for a raid and a rising tide would make the approach navigable for landing craft. This gave only a small window of opportunity.

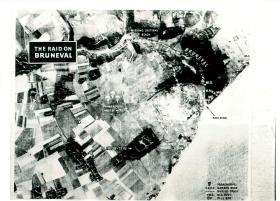

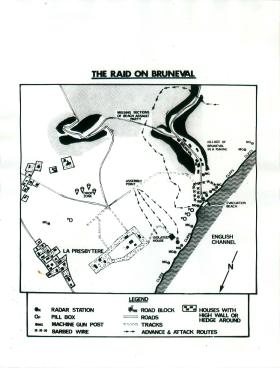

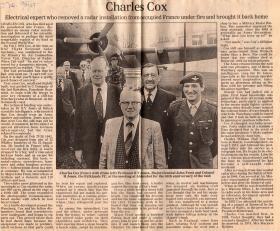

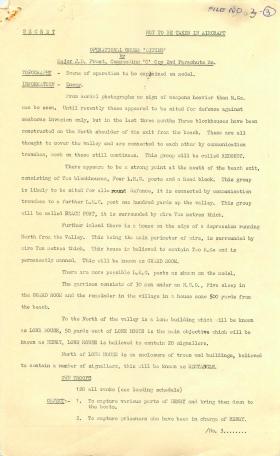

A rough plan was drawn up. The Würzburg radar itself was between the cliffs north of Bruneval and a villa perched atop them. 400 yards north of the villa was an enclosure of buildings and trees called "Le Presbytère" where between sixty and a hundred enemy troops were stationed. At the base of the cliffs, beneath the radar, was a German guard house called Stella Maris and a network of defences called Beach Fort. These stood in the way of a cove the paratroopers would use to escape. The 2nd Battalion's objectives were to capture and hold the Bruneval station, while Flight Sergeant Charles Cox dismantled the radar set. The technician with his liberated radar parts were to be brought safely to the cove for a dawn evacuation by the Royal Navy.

Mountbatten ultimately asked for a company of paratroopers, a section of airborne Royal Engineers, some radar mechanics, planes to drop the men and a flotilla to exfiltrate them. Having secured RAF and Airborne support, Mountbatten submitted the finalised raid proposal to the three Chiefs of Staff (Admiral Dudley Pound, Air Marshal Charles Portal and General Alan Brooke) on January 21. George Millar writes in his history that "Portal was friendly to the proposal, Pound was negative, and Brooke, as so often happened, took the middle ground". But Churchill was keen on the raid, hoping that it would silence the doubters of the 1st Parachute Brigade, formed only six weeks earlier, and the airborne troops who he had always supported. The abundance of PRU photography of the area and the promise of local intelligence from the Resistance ultimately convinced all three men to approve the raid. However, 38 Wing were not able to muster the necessary aircraft and crews in time, so 51 Squadron, led by Wing Commander P.C. Pickard, stepped in. They had twelve Whitleys for the Operation - one for every ten men.

Planning for the raid was conducted in absolute secrecy, such that most of the 1st Airborne Division Headquarters were ignorant of the Operation until the last moment. Emphasis was placed on informing the ground troops before anyone else. Frost himself was originally told a cover story about a practice exercise at Alton Priors to prepare for a further demonstration in front of the War Cabinet at Dover. It was only after voicing his strong objections that he was told in strict confidence about the raid.

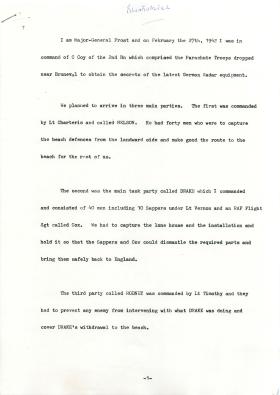

The recently formed ‘C’ Company 2nd Parachute Battalion under the command of Major John Frost was selected by Brigadier Gale to be dropped at night by the RAF; he chose the 2nd Battalion as he wished to keep the 1st intact for a possible battalion-sized operation. But the obvious corollary of choosing such a newly formed company was that they were not even remotely prepared. Many of the men had yet to finish a parachute training course, and they had done almost no training together. Their OC John Frost had failed to complete a parachute course in November and he had to hastily finish one in the third week of January, having only joined C Company in the New Year. Moreover, detailed planning was still going on in late January as Combined Operations were awaiting intel from the French Resistance. For the RAF, this was their largest parachute operation to date, and they practised by dropping dummy parachutists on a variety of pre-determined targets. Poor weather had however put all the elements of combined forces behind schedule.

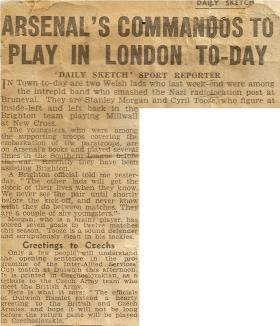

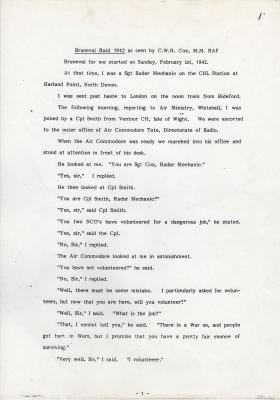

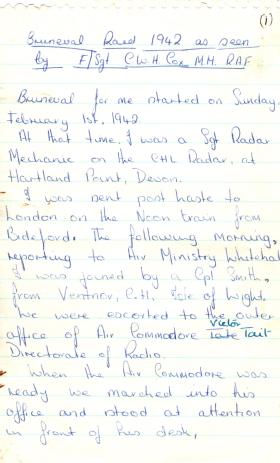

Despite the uncertainty, the Englishman Frost quickly formed a good relationship with C Company, nearly all of whom were drawn from four Scottish Regiments (Black Watch, Cameron Highlanders, KOSB and Seaforths). After completing his six required jumps at the eleventh hour, Frost joined them at Tilshead camp on Salisbury plain, where they had been sent on January 24 to begin training for the Bruneval raid. Frost now began meeting the commanders of the attached units who were also there, including Commander Frederick Cook of the Royal Australian Navy who was in charge of the swift evacuation of the paratroopers. He took time to familiarise himself with the men of the Royal Fusiliers and South Wales Borderers who were tasked with providing covering fire from landing craft while C Company withdrew to the boats. At this time they were joined by the RAF radar operator Charles Cox, who was told he had 'volunteered' for a dangerous mission and was thrust into an expeditious parachute course.

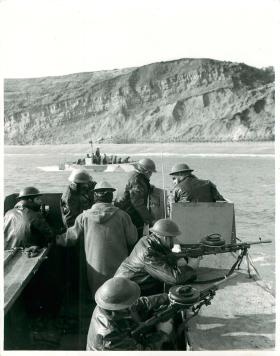

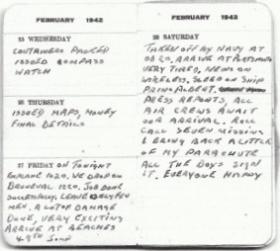

C Company removed their wings and insignia and travelled north by train on February 9, reaching Inveraray on Loch Fyne in Scotland. There they boarded HMS Prinz Albert, a landing craft carrier, to practice embarkations from the side of the ship and pick up from the shore, including at night. This was where some of the famous publicity photographs of C Company were taken. Problems were encountered when the sailors of the landing crafts failed to find the paratroopers waiting to be picked up. Although the issue was never completely ironed out, the solution was agreed to lie in better synchronisation of radio communications. As Inveraray was also the HQ of Combined Operations, C Company were visited by its Chief, Lord Mountbatten, on February 12. Lieutenant John Timothy MC later stated that Mountbatten "blew the gaff" on the raid, but that "we still did not know exactly where we were heading or what we would be doing". When they returned to Tilshead in mid-February, the paratroopers still had serious concerns about the night rendezvous.

Back in Wiltshire on February 15, C Company completed their first parachute training drop as a unit, which went well. But further seaborne exercises around Lulworth Cove caused the issues from Loch Fyne to resurface. All further practice evacuations failed in various ways, with the collapse only becoming more spectacular as the deadline approached. Otway described the lessons learnt in 1951: "rehearsals with the naval force, although relations were good, were not so successful and many difficulties were experienced in arranging times to suit the tides...It would have been far easier to get ready quickly...if all personnel had been trained previously in the elementary routine of combined sea-borne operations".

Execution

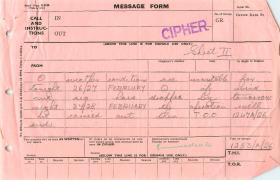

The raid was delayed several times due to unsuitable weather conditions, making the night of the 27/28 February practically the final opportunity. But the conditions were perfect - as Otway put it, "The moon was bright, with very little haze and little cloud; there was no wind or sea swell, and visibility for 51 Squadron in the target area was two to four miles, with good definition".

C Company, 120 men in total, was divided into three groups and five parties (one group containing three). The first group, 'Nelson', containing forty men and commanded by twenty-year-old Lieutenant Euan Charteris, was to drop first at 0015 and secure the beach where the landing craft were due. Captain John Ross, also in 'Nelson', had to hold a road leading towards the evacuation zone. Finally, they were to make contact with the Navy by use of radio or, if necessary, emergency flares. In the second group of forty there were three parties, who were all to drop at 0020 and whose combined effort would capture the main objectives. 'Hardy', twenty men, would capture Villa Gosset itself (as well as any radar operators there) and included John Frost, Charles Cox and the Royal Engineers OC, Charles Vernon . 'Jellicoe', ten men, was commanded by Lieutenant Peter Young and would capture 'Henry' (the nickname for the Würzburg device) and the surrounding area. 'Drake', the final ten men in the third group, were led by Lieutenant Peter Naumoff. They were given the important responsibility of containing the enemy presence at "Le Presbytère" and drawing fire away from Cox and the men dismantling the radar. The final group of forty was 'Rodney', which was to drop latest at 0025 and protect the raid from German reinforcements coming from the southeast and Bruneval village. The men were then to be evacuated in order - Hardy/Jellicoe/Drake first, then Rodney, then Nelson.

Preceding the airborne assault was the naval contingent, which sailed in the afternoon. C Company departed with six officers and 113 ORs later in the evening, who encountered some slight flak as they came across the coast and took evasive action. Fortunately, Fighter Command had launched a diversion beforehand to draw away enemy fighters. But because of the flak two of the Whitleys missed the drop zone by two miles, whilst the others managed to drop their troops accurately. The men dropped short were half of the 'Nelson' party, including Lieutenant Charteris, who would now have further to march to capture the beach. Unbeknownst to C Company, the Whitleys had also been detected by radar and Corporal Schmidt, a Wehrmacht soldier who was defending the beach at Stella Maris, was quickly notified. Guessing that the paratroopers would be exfiltrating from the villa, the Germans (nine men and a Sergeant) rotated their machine gun to point north towards their route of escape.

Charteris and half of 'Nelson' were now in a different valley to the rest of the men, south of Bruneval village; Frost and the others were on the northern side. Speed was of the essence and the fastest route was directly through the village, the only problem being that it contained a garrison of German soldiers stationed at the Hotel Beau-Minet. Charteris realised that the rest of the men depended on them for the capture of the beach, and so the men of 'Nelson' jogged past the garrison. They may have been helped by the snow cover dampening their footsteps, but eventually they saw the enemy and had to dart off the main road towards the beach. At this moment an unfortunate German soldier fell in with them, probably having been alerted to the raid and thinking the paratroopers were Wehrmacht soldiers running to confront it. At about the same time the paratroopers and the German realised they were enemies. Charteris turned around to shoot the man with a revolver but forgot to turn the safety off, whilst the German panicked and fired his rifle, but missed. Sergeant Gibbon spun to fire his STEN and Private Hill threw himself out of the way, with the shot killing the German. It was later rumoured that the soldier was killed with an FS knife - George Millar's book claims he was killed "silently" - but the historian Taylor Downing has stated this is a myth.

On the other hand, the main drop had gone smoothly and the remaining men assembled as planned. They ran to their weapon containers and retrieved their Lee Enfield Rifles, STEN and BREN guns. When Frost reached the villa, he noticed the door was wide open. With 'Hardy', 'Jellicoe' and 'Drake' in position, they waited for the four blasts from Frost's whistle that signalled them to attack. The moment he heard it, CSM Gerald Strachan threw some grenades into the basement and fired his STEN inside the building, but nobody was there. Meanwhile, Lieutenant Young, Jellicoe's leader, approached the radar pit and was stopped by a sentry, who was quickly dispatched. After clearing the pit, Cox was allowed to begin his work with sappers from the Royal Engineers. In the chaos, Young was able to capture a soldier who was brought to Frost's translator. But at that moment a German opened fire on the sappers from the first floor of the villa. Strachan rushed upstairs and killed him before he could jeopardise their work. The captured soldier claimed that there were 200 men in Bruneval and 100 in "Le Presbytère", which would leave C Company outnumbered three to one if they were mobilised.

Some of the Germans were not well prepared and had been killed before they knew what was happening. Although they had been slowed down by snow and wire obstacles, the Royal Engineers were now also making good progress. The only problem was that fire was now gradually pouring out of "Le Presbytère" at a steadily increasing rate, with 'Drake' unable to contain it. As a result, Private Hugh McIntyre was killed by a sniper as he exited the villa and two others were injured. Meanwhile, the Royal Engineers were forced to dismantle the radar with bullets passing overhead. Cox recalled "bullets were flying much too close to be pleasant...two bullets hit the apparatus, but most of the machine gun fire went high". Frost ordered Lieutenant Naumoff and the men of 'Drake' to return fire. Cox's screwdriver was now not long enough to reach the fixing screws inside the radar. When Vernon turned on his flashlight to take pictures, he attracted more high accuracy shots, so that the paratroopers nearby swore at him whenever he did so. Frost ordered him to turn it off. The decision was made to forcibly remove parts of the radar with hammers and crowbars. While Cox and Vernon held it, Corporal Jones was eventually the one to tear a large part of the frame off, which included a vital switching unit.

Shortly before Frost and his men withdrew to the beach at 0145, three vehicles were observed moving to reinforce "Le Presbytère". He ordered the engineers to stop their work and make for the sea with what they had. They had been promised thirty minutes to work but only received ten. After the radar parts were loaded into trolleys, the sappers blew up what remained of the Würzburg. As they descended the cliffs to leave, CSM Strachan was injured by an MG42 on the far side of the valley, being shot 7 times. Remarkably, he survived. All of this was complicated by recently formed snowdrifts and the steeper than expected descent. Now on a heavy dose of morphine, Strachan had to slide down the cliffs.

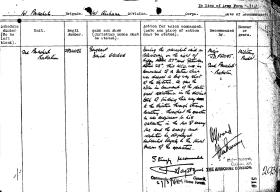

Without Charteris and the full strength of 'Nelson', Captain Ross and his men were pinned down on the beach by the same MG42 that wounded Strachan. Luckily, the young Lieutenant arrived at that very moment (around 0200) from the south and took control of his objective. His men threw two rounds of grenades at Stella Maris. Then, covered by fire from Sergeant Tasker and his squad, Charteris and the others ran into Stella Marris itself. Sergeant David Grieve, directly behind Charteris, shouted 'Caber Feidh' as the men descended on the building, and the rest of the men joined in. This was the war cry of the Seaforth Highlanders. The telephone operator Corporal Schmidt was still inside from earlier, and he surrendered. The rest of the German soldiers on the beach melted away as Captain Ross also advanced.

Radio communications, which had been a continuous source of frustration during the rehearsals, did not prove more reliable now. Whilst the men could shout to one another to overcome this, the more salient point was that the Navy could not be alerted to their position. With the whole of C Company assembled on the beach at 0215 hours, and no sign of the landing crafts, the situation looked grave. 'Nelson' were duly ordered to guard the entrance to the beach, and the red emergency flare was fired; this seemed to do the trick as HMS Prins Albert appeared shortly thereafter. The Navy's radios came into range as the boats entered within 250 yards. However, the careful evacuation order was quickly abandoned as all six landing craft beached at once under a hail of covering fire from the Royal Fusiliers and South Wales Borderers. who formed a defensive perimeter. In the ensuing confusion, some landing crafts were crammed full of men whilst others were partially empty. Everyone, including the radar equipment, POWs and wounded, were nonetheless on the boats before the last one departed at 0315. Two miles from the shore they transferred into gunboats for a swifter passage across the channel.

It later emerged that HMS Prins Albert and the Navy had received no radio signals during the whole raid, and had purely found the men thanks to their red Verey flare. Moreover, Commander Cook and his ship had only narrowly avoided detection by a German naval patrol when it passed them at close range. Consisting of a destroyer and two 'E' boats, the patrol would no doubt have made the Bruneval raid a failure had it discovered the evacuation force. But with C Company on its way home, their escort only became stronger when it was joined by four destroyers and a squadron of Spitfires. Although the sea rescue was delayed, the raid went according to plan and was a complete success, capturing not only the radar equipment but two German radar technicians. Churchill was so satisfied with the raid that he called the War Cabinet to hear the story from C Company themselves on March 3.

The Bruneval Raid later became The Parachute Regiment’s first Battle Honour. It gave the nation a small but exciting taste of success at a time when the war was going badly. Importantly, it reaffirmed Churchill’s belief in the future of Airborne Forces, while muffling its critics.

Battle honour conferred:

Bruneval

Compiled with information from:

The Second World War 1939-1945 Army: Airborne Forces (1951), Lt. Col. Terence Otway, DSO

The Bruneval Raid (1974), George Millar

A Drop Too Many (2002), Major General John Frost CB DSO MC

'The Night Raiders of Normandy' part of The Amazing War Stories Podcast by Bruce Crompton. https://www.amazingwarstories.com/podcast/the-night-raiders-of-normandy/

Night Raid (2013), Taylor Downing

Tim's Tale (2008), Harvey Grenville

Airborne Assault Archive

Article rewritten by Alex Walker 04/03/2024

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.