The Battle of Sangshak is probably the least talked-about battle by a British parachute brigade: the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade. It is a tale of Arnhem, D-Day and North Africa rolled into one, fought by British, Indian and Nepalese soldiers, in a forgotten battle that turned the tide in the battles for Imphal and Kohima and saved Lt General William Slim’s XIV Army from potential defeat. It is a tale of dogged determination in the face of overwhelming odds and a withdrawal like no other. This will be the first of several posts during March about the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade and the Battle of Sangshak.

Countdown

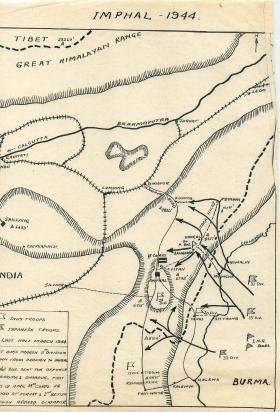

The Battle of Imphal/Kohima was fought over a huge area by huge numbers of troops. The fighting was hard and bitter in all areas from mid-March to July 1944 and the rout of the Japanese. Our focus is on one small heroic action by one small group amongst many small heroic actions by many small groups in a huge theatre of war.

This is a very simple account of the campaign to give context for the role and actions of 50th Indian Parachute Brigade.

The Allies had been building up their forces in north-eastern India for their planned counter-offensive Burma when it became clear that the Japanese were planning an invasion of India.

Intelligence expected that the Japanese invasion would start on 15 March, directed at Imphal in the south. The British plan was to withdraw from their southern outposts to the Imphal plain to make their stand in accordance with Slim’s plan.

Intelligence also suggested that there would be an attack in the north and an attempt to cut the Imphal-Kohima road. Due to the terrain, it was thought that this would be an action by a Japanese Regiment at most (at this point you should be thinking ‘Ardennes’).

The Japanese in the south started their invasion on the 8 March, a week earlier than expected. By 12 March the Japanese had got behind the British 17th Division and cut the road to Imphal. The 17th began its withdrawal on 14 March and, for the next two weeks, had to fight its way out.

Simultaneously the Japanese had also launched an attack from the South east towards Imphal. The British rushed reinforcements south, which included the 49th Brigade from the area of Ukruhl and Sangshak.

The movement of these units left Imphal depleted of units and with much less protection in the north. This, of course, was the Japanese plan: that reserves would be drawn southwards. The movement of the 49th Brigade south resulted in the 50th Indian Parachute Brigade occupying the Ukruhl and Sangshak region.

From 15 March, heavy fighting took place is this southern area. The route was not reopened until 28 March and the 17th Division did not arrive back in Imphal until 4 April.

In the south-east, on 16 March, the British started their withdrawal to pre-prepared defensive boxes. However, the reserves had been committed to the southern sector and there were none available for the south-east, so they withdrew further and faster to their last defensive box in the Shenam Saddle.

Although the Japanese never got further than the Saddle, they had occupied one of its hills by 26 March 1944.

Meanwhile, The Japanese now launched their attacks in the north on 15 March – not just a regiment, but nearly two whole divisions – their objectives being to attack Imphal from the north, cut the Imphal-Kohima road and to attack Kohima before moving onto Dimapur and into India.

The Japanese 31st Division ran into 50th Parachute Brigade at Hill 7378 on its way to Ukruhl and Kohima. The divisional commander decided that he could not bypass and leave this deadly force in his rear.

Instead of heading north to Kohima, the 31st Division waited and headed south to Sangshak to deal with the Indian Army’s 50th Parachute Brigade, probably because of the fierce fight it had had at Hill 7378.

This meant that part of the force heading to Imphal was also held up, the 15th Division waiting for the 31st to finish its job before moving onto Imphal.

From 19 to 26 March the battle in the Sangshak area raged. All the time Japanese units were heading north to Kohima and flowing around Sangshak to cut the Imphal-Kohima road and attack Imphal.

In almost the same period, from 18 to 27 March, the 5th Indian Division was flown into Imphal from the Arakan to shore up the vulnerable northern defences of the Imphal plain. Units were rushed into the line as soon as they got off the aircraft.

The 50th Parachute Brigade had delayed the Japanese attack from the North east long enough to allow the reserves to get into place.

The Japanese pressed their attacks around Imphal and the British withdrew to defensive positions. There was no rout of the British, who were resupplied by air. Whilst the fighting was ferocious, the Japanese never gained Imphal and the rest, as they say, is history.

Prelude to Battle

Anyone taught to read Ordnance Survey maps — probably a fair proportion of this readership – will only to have to look at the contour lines on the maps in this article to realise that this is serious hill country! Of course it is: we are in the foothills of the Himalayas.

The terrain around Sangshak consists of steep-sided valleys running north to south and clad in thick jungle. Traversing east to west entails scaling 3000 ft to 5000 ft peaks and ridges, dropping into valleys, climbing back up again, over and over again ad nauseam. Very difficult terrain to cover at every level from section up to division.

In his book The Battle at Sangshak, Harry Seaman paints a picture: “ …it is difficult to convey the totality of conditions here….the climate is horrendous…along with the monsoon came the malaria season as well as a variety of diseases….scrub typhus, cholera, scabies… Naga sores caused by pulling off leeches and leaving their heads buried in your flesh…..[outside the monsoon]water became a precious commodity in the hill villages…”.

The few good roads that existed in 1944 clung to the side of the hills. Eric Nield, Medical Officer with 153rd Parachute Battalion, recalled how they felt sick in the back of the truck as they swung around a ceaseless series of hairpin bends. The closer the Brigade got to its area of operations, the less the roads were suitable for anything other than jeeps and mules.

It was, of course, this terrain and the British underestimation of the ability of the seasoned jungle fighters of the two Imperial Japanese Army divisions spearheading the planned invasion of India that nearly resulted in the disaster that this battle could so easily have become.

In Field Marshal Viscount Slim’s own words from his book Defeat into Victory: “I had been confident that the most the enemy could bring and maintain through such country would be one regimental group, the equivalent of a British brigade group. In that, I had badly underestimated the Japanese….”.

This is somewhat reminiscent of Field Marshall Montgomery’s underestimation of the ability of the Germans to regroup at Arnhem.

So, it was into this harsh environment that 50th Parachute Brigade was inserted early in March 1944, its units shaking themselves out and establishing operational bases in the area containing Jessami, Ukhrul, Sangshak, and Sheldon’s Corner.

The Brigade was under the overall command of 23rd Indian Infantry Division. According to the Brigade’s War Diary, it was tasked with: “…prevention of JAP infiltration by way of SOMRA tracks.”. These were the tracks that came from eastern Burma across the river Chindwin into India and thence towards Jessami, Ukruhl, Sangshak and Sheldon’s Corner.

The War Diary also notes a few transport issues around this time, like the fitting of mule saddlery, an indication of how movement in this terrain was accomplished. There is a reference to no movement possible owing to the state of roads because of rain.

The Diary also notes the loss of several vehicles en route. This entry was on 17th March, some two weeks after the leading divisional elements had reached the area.

Elsewhere, however, events were moving very quickly. The Japanese had now launched their attacks in the south; by 17th March they had cut off the 17th Indian Division from Imphal and in the south-east, the British withdrawal to prepared defence positions had begun.

This resulted in re-enforcements being sent from the Ukrhul area and set the scene for 50th Indian Parachute Brigade to step into the breach. It should be remembered that the British High Command was not expecting a two-division Japanese attack in this direction and that even now, some ten days after the Japanese commenced their attacks, the British were still unaware that two enemy divisions had crossed the Chindwin on 15th March.

The War Diary records the situation on 18th/19th March. The troops now under command of 50th Indian Parachute Brigade and their dispositions were as follows: 4/5 Mahratta Light Infantry at Kidney Camp with the 582 Jungle Mortar Battery; 152 Parachute Battalion at Sheldon’s Corner; the Kalibahadur Rifles at Sangshak; the MMG Company at Ukruhl; 153 Parachute Battalion at Imphal.

With masterful understatement, the 50th’s War Diary records on 18th March: “A coln of Japs advancing via Pushing, having attacked V force, was likely to bump 152 Bn at SHELDON’S CORNER within the next 2 days.”.

In fact, it was only eleven hours later that 152 Para Bn were ‘bumped’ and thirty-six hours later that the Battalion’s C Company had been annihilated but we will return to that in Part 4.

Nobody — the British High Command in South East Asia, the commanders on the ground and more importantly, Brigadier Julian Hope-Thompson commanding of 50th Parachute Brigade — had any idea of the tsunami of Japanese infantry now rolling towards them.

And all that stood in the way of the Japanese invaders in these vital few hours and days was 50th Indian Parachute Brigade.

Contact. Wait Out.

Major John Fuller, Officer Commanding C Company, 152 Parachute Battalion, complete with broken leg in plaster from a training accident, had been in position on Hill 7378 some miles to the east of Sangshak since 17 March.

They had taken over from the 49th Infantry Brigade, which had moved to Imphal. There were some defensive positions, which were improved by C Company, but this was by no means a defensive box. It was the top of a hill with some trenches. It was only ever supposed to be a base from which forward patrolling would take place.

And so it was on 19 March that Japanese infantry from the 3rd Battalion, 59th Regiment commenced their attacks on C Company. On the forward slope, C Coy’s advance trenches were quickly overwhelmed in the Japanese attack. Time and again the Japanese attacked, ground was lost and gained, until eventually during the night the Japanese withdrew to regroup.

The men of C Company had their first taste here of the Indian National Army, formed by the anti-British Indian Nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose. This was an army of Indian Volunteers who chose to fight on the side of the Japanese, spurred on by the desire for Indian independence from the British. The INA soldiers called out to their compatriots on Hill 7378 exhorting them to change sides. We cannot print the replies for fear of complaints!

During the battle on the 19,152 Battalion HQ had established itself to the rear at Sheldon’s Corner, overlooking Hill 7378, while they worked out how to support C Company. It was here that the scale of the Japanese invasion from the east began to become apparent. To their horror, not much further to the east, some 800-900 Japanese soldiers were seen heading in their direction.

Whilst C Company repelled the waves of Japanese attacks over and over again, they saw their numbers whittled away as the toll of killed and wounded mounted. For the Japanese, the situation was tactically similar. In strategic terms, so began a series of events at Sangshak that would eventually spell disaster for the Japanese campaign.

Whilst C Company put up tremendous opposition, the Commanding Officer, Lt Colonel Paul Hopkinson, devised a plan together with Lt Colonel Jack Trim of the 4/5 MLI to relieve C Company.

Hopkinson despatched A Company, 152 Para Bn to outflank the Japanese attack but the steep-sided jungle-clad terrain was too difficult for A Coy to get to C Company in time. Trim despatched A Company 4/5MLI to attack along the road.

A Coy took their objective but were unable to press on due to Japanese resistance. This was another small but vicious action during which Lance Naik (Corporal) Desai won the Military Medal and Jemadar (Lieutenant) Desai the Military Cross.

The 50th Indian Parachute Brigade War diary records that at 08:00 on 20 March, Major Fuller was reported killed and that by 10:30 that the Japanese had finally overrun C Company. Of the 120 or so men of C Company, only around twenty survived. The Japanese estimated their losses at 160 killed.

Whilst all this was happening the 153rd Gurkha Parachute Battalion moved south from Kohima to Imphal.

The Brigade Deputy Commander, Colonel Bernard Abbott, had walked the nine miles from Brigade Rear HQ at Litan to Sheldon’s Corner with the Intelligence Officer Captain Dicky Richards. Abbott agreed a plan with Hope-Thompson to withdraw the 152nd to Kidney Camp.

There can perhaps be no better way to describe the shock of what had happened than to use the words of Captain Eric Nield, the 153 Gurkha Parachute Battalion’s Medical Officer, on the morning of 21st March in Imphal:

“We had barely finished breakfast when the incredible news arrived. The two leading companies of 152 had been overrun. Where had the Japs come from? If ‘I’[Intelligence] was correct they should be some hundred miles the other side of the Chindwin. The situation was roughly comparable to a Londoner being told that the Germans had appeared in Tonbridge, and not by parachute either. We were flabbergasted.”.

Brigadier Hope-Thompson was desperately trying to impress upon Divisional HQ the parlous state of affairs. But Divisional HQ had its hands full with what was going on in the south as the Japanese pressed home their attacks towards Imphal.

Nobody is really clear at what point the British truly understood the nature of the Japanese invasion and the size of the force now moving on Kohima and Imphal from the north. Even at this stage, it is unlikely that they knew the true size of the enemy forces.

The 153rd were now rushed back up from Imphal to Litan. Part of the battalion stayed at Litan while the rest were scheduled to move to reinforce the MMG Company at Ukhrul. As events rapidly unfolded, the 153 never made it to Ukhrul. The plans changed. The MMG Coy destroyed the supply dump at Ukhrul and both the MMG Coy and the 153rd went to Sangshak.

During this time, Japanese patrols were moving west to cut the Kohima-Imphal road. Right in the middle of this was the Litan Box. Here was Brigade Rear HQ, one company of the 153rd Gurkha Parachute Battalion and most of the 411 Parachute Field Squadron Indian Engineers.

Jack Newland, 2ic 153rd, was appointed Litan Box commander. From 22 March onwards this force was attacked nightly by the Japanese, with the 411 PFS bearing the brunt of the enemy assaults.

While the Japanese 3rd Battalion, 59th Regiment was attacking C Company on Hill 7378 on its way towards Litan to cut the Imphal-Kohima Rd and attack Imphal from the north; the 59th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion should have headed through Ukhrul to Kohima.

However, and most likely due to the resistance mounted by 50th Brigade, the Japanese could not afford to leave such a strong force in its rear, the 2nd Battalion diverted from its mission and headed towards Sangshak.

50th Indian Parachute Brigade were unravelling the Japanese plans. They had caused heavy losses, expenditure of ammunition, battle fatigue and cost the enemy two days already and now they had caused another Japanese battalion to divert from its mission and take up the fight against them.

All the time gained here by 50th Indian Parachute Brigade was used by General Slim to rush reinforcements into Imphal while Kohima also strengthened its defences. The 50th were instructed to hold at all costs and destroy the enemy or cut the enemies lines of communication.

Brigadier Hope-Thompson, in consultation with 23rd Division, chose Sangshak as the base for its defensive ‘box’. And so began a race against time for the dispersed units to get to Sangshak before they were cut off by or engaged by the Japanese Infantry.

Even then, it is doubtful that anybody realised that Sangshak would become The Parachute Regiment’s Rorke’s Drift.

Source:

Written by John Gerring and fellow members of The Arnhem Fellowship

Read More

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.