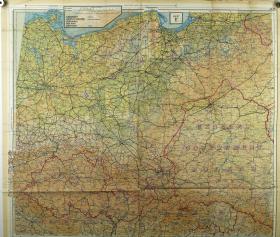

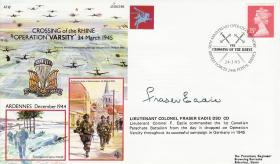

By late January 1945, the Germans' Ardennes offensive was finally defeated. It had been a costly episode for both sides, but more so for the Germans, who now had to retreat across the Rhine greatly weakened and "in no condition to hold fast even in these positions". Eisenhower was approached by Field-Marshal Montgomery with a plan to clear the area from the river Meuse eastwards and secure a foothold along the banks of the Rhine from Dusseldorf to Nijmegen. By February 13, the British and Canadians were in a joint push towards Goch on the border, while the Canadians had also reached the city of Emmerich am Rhein further north. By the end of February, the Ninth U.S. Army had captured Munchen Gladbach, within the borders of Germany. In quick succession, the First U.S. Army secured a railway bridge at Remagen on March 7, securing the first bridgehead on the far side of the Rhine river. By the third week of March, the Allied Army - four million men in all- were on the banks of the Rhine practically from its source to the sea, setting the scene for Operation Varsity.

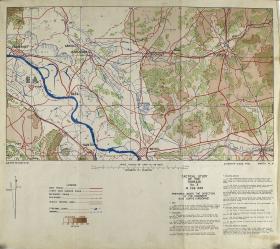

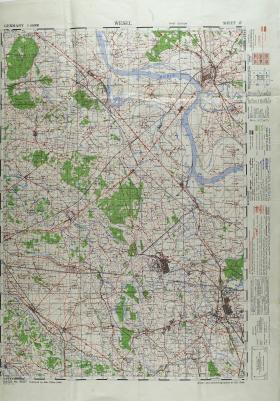

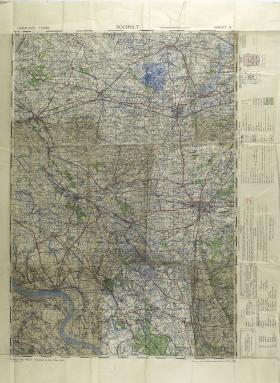

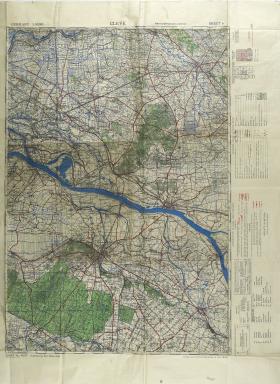

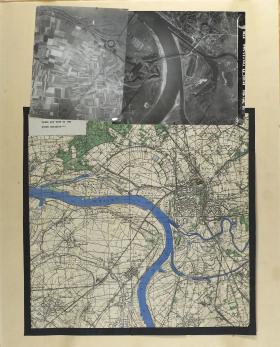

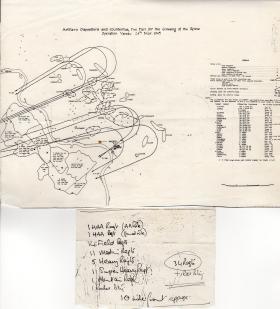

Montgomery's overall plan for the Rhine crossing, Operation Plunder, was issued on March 9. The Ninth U.S. Army would be on the right whilst the Second Army, which included the Brits and Canadians, would be on the left. Together they would cross the Rhine between Rheinberg in the north and Rees in the south, on a front of about 35 kilometres. Wesel, a communications centre situated in the middle of the front, was the principal target, with the date for the Operation set for the night of March 23/24. If successful, the crossing would allow a rapid takeover of the Ruhr's industry and leave the North German plain exposed to the two armies, effectively ending the war within weeks. But at 300 metres wide and with a current of around 5 miles per hour, the Rhine was a formidable barrier.

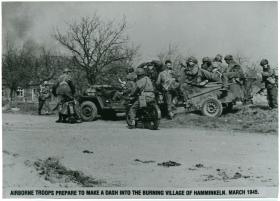

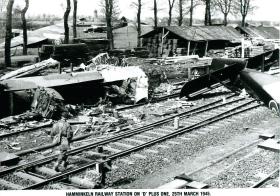

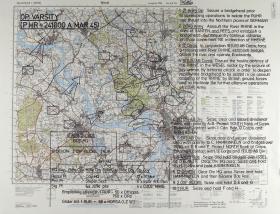

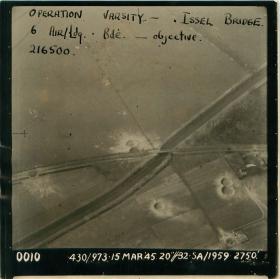

The Airborne component of the plan, Operation Varsity, would be overseen by the First Allied Airborne Army, commanded by Lieutenant General Lewis Brereton. Its first target was the Diersfordt Wood, a thick forest 200 feet above the level of the Rhine. Not only did the road to Wesel pass through here, but it was feared that German artillery could launch attacks from the wood onto the advancing ground troops. The village of Hamminkeln was to be the second target, owing to a large number of roads converging there. It was feared these roads could be used to bring in reinforcements for a counterattack. Furthermore, the tiny river Issel next to Hamminkeln would slow down allied tanks if it remained in enemy hands, and had to be secured.

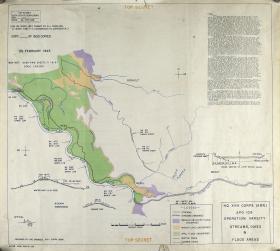

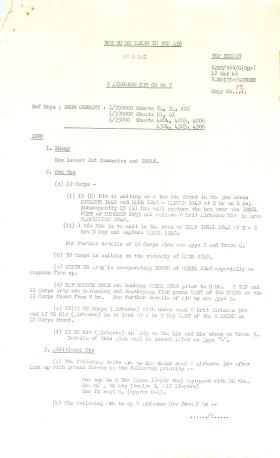

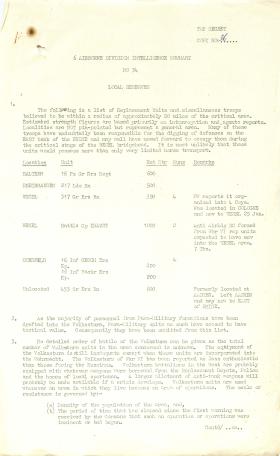

Facing the allied troops in the area was the German 1st Parachute Army. The divisions most closely involved in the defence were the 7 Parachute Division and the 84 Infantry Division, but both of these were severely understrength at less than 4,000 men each. On the other hand, they were thought to have 150 armoured vehicles and were starting to expect an airborne assault. On March 17, there were only 153 light and 103 heavy flak guns estimated to be in the area. But by March 23 their anti-air capability had increased, with 712 light and 114 heavy flak guns. The heavy guns were those of 88m and above. Originally commanding the defence of the Wesel sector of the Rhine was General Alfred Schlemm. However he was injured two days before the Operation and was replaced by General Günther Blumentritt. Blumentritt knew the Allies would choose the airborne route, but he had no time to erect anti-glider poles. He set about fortifying every available farm in the area.

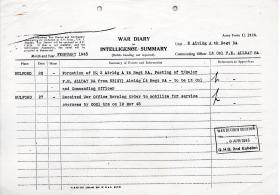

6th Airborne Division was initially to be partnered with the 13th and 17th US Airborne Divisions for the purposes of Varsity, but the 13th was left out as there were not enough transport aircraft. The 6th (British) and 17th (American) were put under the overall command of the 17 US Airborne Corps. It was decided that the whole drop, both American and British, would take place in a single lift.

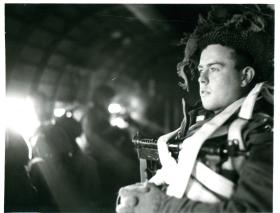

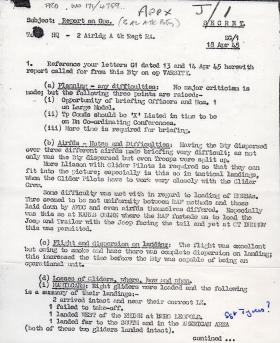

Daylight airborne operations had proven superior by this point in the war, and with complete control of the air it was decided without hesitation to launch the Varsity drop at day. But for the first time it was also decided to launch the airborne assault 13 hours after the amphibious crossing, after several bridgeheads had been secured. Doubtless the failure of 30 Corps to reach the bridge at Arnhem in time was also in the planners' minds in this regard. Otway confirms this when he writes that the LZs and DZs were deliberately placed within ground artillery range, with the plan stipulating a link-up with ground forces on the first day of the Operation. He continues:

"Among the lessons learned from the Arnhem operation was the fact that if possible the complete division should be brought into action in one lift, and that landing and dropping zones should be as close as possible to the initial objectives. In this way there would be little time for enemy reaction to develop and our troops would be able to maintain their initial advantage of surprise."

17th US Airborne Division under command of Major General William Miley was to drop in the south of the operational area at 1000, March 24. Their targets were the high ground east of Diersfordt and the southern crossings over the river Issel. 6th Airborne Division under command of Major General Eric Bols was to drop in the north of the operational area, also at 1000. Their tasks were to secure the high ground near Bergen, Hamminkeln and the northern crossings over the Issel.

6th Airborne Division consisted of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, the 5th Parachute Brigade and the 6th Airlanding Brigade. 3rd Parachute Brigade, which included the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, were to drop onto DZ 'A', near the northwest corner of Diersfordt wood, and capture the 'Schnappenberg' feature. They then had to hold the western edge of the Diersfordt wood, capture the road junction at Bergen, and hold the railway line running through the north east of the wood. 5th Parachute Brigade were to drop onto DZ 'B' and hold an area which included a main road leading to Hamminkeln. They were then to patrol westwards towards the railway line which 3rd Parachute Brigade had hopefully captured. At this point the two brigades would meet up.

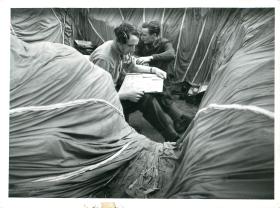

6th Airlanding Brigade had multiple objectives assigned to different battalions. 12th Battalion, The Devonshire Regiment, were assigned to LZ 'R', south west of Hamminkeln, and were tasked with capturing the village itself. 2nd Battalion, Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, were assigned to LZ 'O', north of Hamminkeln, and had to seize the nearby road and rail bridges over the Issel. Finally, 1st Battalion, The Royal Ulster Rifles, were assigned to LZ 'U', south of Hamminkeln, and were to capture another major bridge over the Issel and the surrounding area. Divisional HQ were to drop on LZ 'P' and establish headquarters at Köpenhof farm.

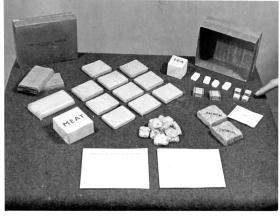

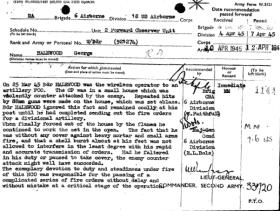

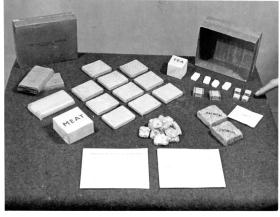

Bols was first notified of Varsity on February 18. The Operation would make use of the new Horsa Mark II, which had a hinged nose to allow for quick unloading. More gliders were to be used than had ever previously been allowed to bring in more weapons, jeeps and ammunition. Furthermore, officers of the 2nd Forward Observer Unit, RA, who would be dropped by parachute, would coordinate the artillery bombardment coming from the west bank of the Rhine. Pathfinders were not used with the reasoning that the battle would already be underway, so there would be no difficulty finding the DZs. Ironically, Varsity would be the last ever action which used glider-borne troops.

To enable the laying of tracks for vehicles and taped routes for infantry, an artificial smokescreen was deployed continuously between dawn on March 21 and 1700 on March 23. One of the smoke generators is held in the reserve collection of the Airborne Assault Museum. Brian Jewell, a historian and soldier from the Royal Engineers, described the scene on March 23: "throughout the day, concentrations of men, equipment and vehicles built up behind the continuous smokescreen in an atmosphere resembling some vast bizarre fairground in fog...At around 1730 hours, smoke dischargers were shut off; and at 1800 hours precisely, the entire artillery of the Second British Army and the Ninth US Army opened fire, their shells and 'magic carpets' of rockets passing over the heads of the assemblies of men". The shellfire continued until 0945 on the morning of March 24, shortly before the first parachute drops took place.

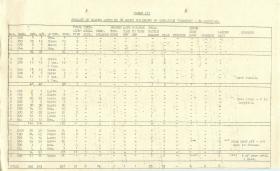

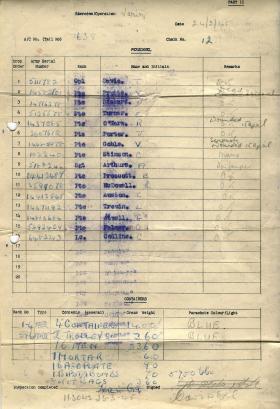

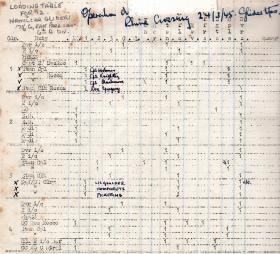

Of the aircraft allocated to the 6th Airborne Division there were 440 gliders (146 Horsa Mk. I, 246 Horsa Mk.II and 48 Hamilcars) and 243 parachuting aircraft (Dakotas), for a total of 683. Of the Dakotas, 3rd Parachute Brigade had 122 whilst 5th Parachute Brigade had 121. All these aircraft took off on March 24, but not all reached their destination. These figures come directly from Appendix B to the 6th Airborne Division's Operational Orders for Operation Varsity, March 1945. It is worth noting that the numbers of British aircraft listed on Wikipedia are massively inflated compared to these official accounts.

The Dakotas were flown by American pilots of IX Troop Carrier Command, whilst the glider tugs were flown by No. 38 Squadron and No. 46 Squadron RAF. Coordinating the arrival of such large numbers of aircraft from two divisions was no easy feat. The aircraft took off from 26 different airfields in two different countries (11 in England, 15 in France). The English transports rendezvoused over Hawkinge in Kent before joining the Americans over Wavre near Brussels. Lieutenant General Gavin's comment that the formation "contained at least five elements of different characteristics and speed" is an apt one. In the same vein, Otway comments that, "whereas the fly-in of 6 Airborne Division was completed in 40 minutes, that of 17 U.S. Airborne Division took two and a half hours".

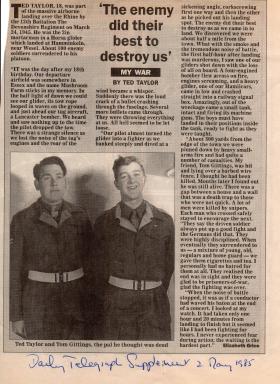

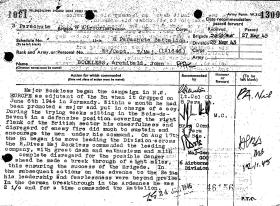

On the morning of March 24 the weather was perfect for flying with excellent visibility. Parachute drops began ahead of schedule. Unfortunately, 18 Dakotas were destroyed and 115 returned damaged by flak. Meanwhile, of the 440 gliders, 35 had to abort on the journey. The remaining were released into the leftover smog created by British engineers over the LZs, though it was also a by-product of bombing, artillery and flak. Brigadier G.K. Bourne wondered if the bombing of Wesel had been mistimed, as it was still so dusty; it had actually happened on time. Lt. Col. G.F. Eadie stated "our own artillery was still firing on their targets as the troop carriers approached the Drop Zone. The smoke and dust from their firing practically obscured the ground while above all this, a cloudless sky and brilliant sunshine was to be the order of the day". Jewell states that the dropping area "was shrouded in the smoke of the action that had been raging through the night [artillery] and in the suspended rubble dust resulting from the destruction of Wesel twelve hours earlier, obscuring the low ground". However, there is no mention of deliberate smoke generation after 1730 on March 23.

Gavin described the scene:

"It was an indescribably impressive sight. Three columns, each nine ships or double-tow gliders across moved on the Rhine. On the far side of the river it was surprisingly dusty and hazy...The air armada continued on and crossed the river. Immediately it was met by, what seemed to me, a terrific amount of flak. A number of ships and gliders went down in flames and after delivering their troops, a surprising number of troop-carrier pilots we saw on their way back were flying planes that were afire. The crew that I was with counted twenty-three ships burning in sight at one time. But the incoming pilots continued on their courses undeterred by the awesome spectacle ahead of them".

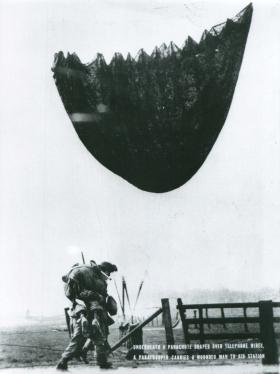

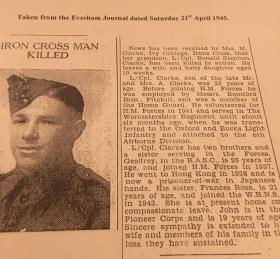

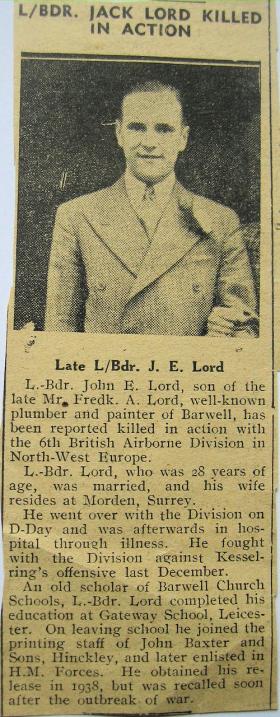

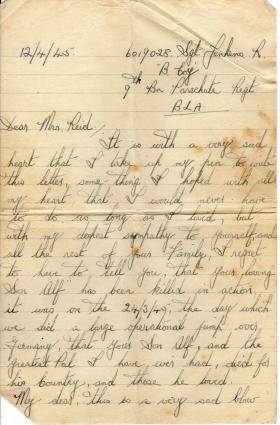

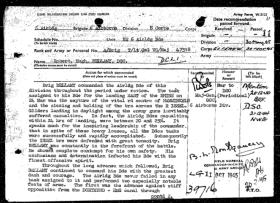

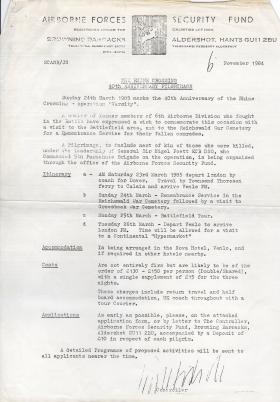

The 3rd Parachute Brigade dropped its first men at 0951 hours, March 24, just outside the Diersfordt wood, but encountered heavy resistance from men firing from the woods. This caused an estimated 270 casualties. Nonetheless, the DZ was secured by 1100 and the primary objective of the Schnappenberg feature was captured by the 9th Parachute Battalion at 1345. Meanwhile, the 8th Parachute Battalion was ordered to move east and then clear the woods west of the Divisional HQ at Köpenhof farm. At about 1545 ground troops from the 44 (Lowland) Infantry Brigade joined up with the 3rd Parachute Brigade. By 1700 on the first day the 3rd Parachute Brigade had killed around 200 Germans and taken 700 prisoner, whilst they had lost 270 paratroopers dead, injured or missing. A significant number of men had been shot after getting their chutes caught in trees. One of the men killed in this manner was the CO of the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, Lt. Col. Jeff Nicklin.

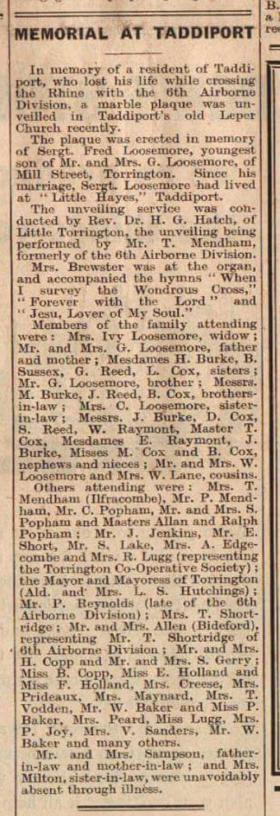

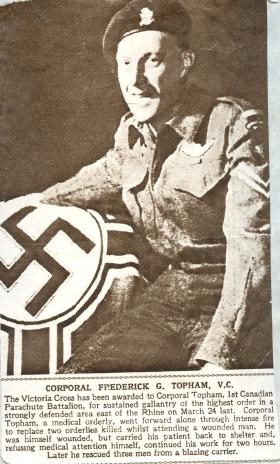

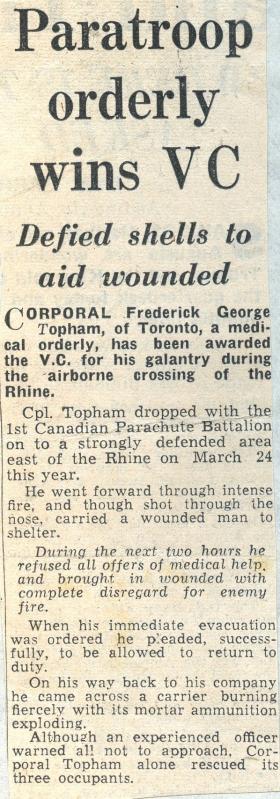

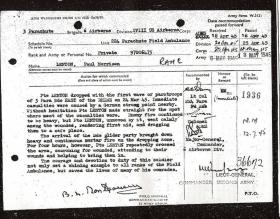

The Canadians, who were part of the 3rd Parachute Brigade, left for Varsity aboard 35 aircraft. Their drop occurred at 0955 hours, and by 1130 they had secured all their objectives. One of their men, Corporal Frederick Topham, won the Victoria Cross on this Operation for saving several men's lives. Alan Brooke later stated of the Battalion, "In the battle which followed the crossing of the Rhine on March 26th, 1945 its performance was again of the highest quality, in spite of the much regretted death in action on March 24th of their fine commanding officer".

5th Parachute Brigade's drop was not quite as accurate as the 3rd's, and the smokescreen made it difficult for the men to assemble. Once again, the DZ came under heavy gun and artillery fire, but the 7th Parachute Battalion managed to get into position to cover the landings. The 12th and 13th Battalions set to work clearing out the nearby farms and houses, nearly all of which were manned. By 1530 the main road running into Hamminkeln had been captured and a rendezvous with 6th Airlanding brigade achieved.

6th Airlanding Brigade had perhaps the hardest task considering the smoke cover and intense flak on the approach. Writing in 1951, Otway appeared not to know the source of the smoke, writing, "whatever the cause, a very effective unintentional counter-measure against glider landings was constituted either by our own side or by the enemy". He described gliders landing in the wrong place, crashing, or being set alight by enemy fire. Thankfully the coup de main parties landed on their objectives with extreme accuracy. The Royal Ulster Rifles' six gliders landed on both sides of their target bridge and captured it instantly, whilst the Ox and Bucks landed on one side but were also successful. By 1100 the relevant Issel bridges and Hamminkeln itself were captured. As more airlanded troops poured in they cleared the surrounding neighbourhoods with the help of the 513 US Parachute Infantry Regiment, who had been dropped too far north. Thankfully the Americans had accidentally dropped on a battery of 88m AA guns which were actively destroying gliders, which they quickly neutralised. 6th Airlanding Brigade had managed to capture 650 prisoners by the night of the 24th, with Brigade casualties estimated at 30 percent.

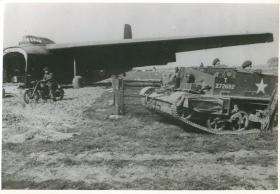

During Varsity, the M22 Locust Tank saw its first operational use by British airborne forces. Unfortunately, its performance left much to be desired:

"Eight light tanks (T.A. Locust) of the Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment were flown into the operation and of these four reached the rendezvous successfully but only two were 100 per cent fit for action. Of the others, one was missing, another overturned on landing, a third was set on fire, and a fourth was put out of action...the Tanks formed a strong point on the edge of the woods west of divisional headquarters".

On the other hand, artillery support worked extremely well, with Otway commenting, "The fire of the two medium regiments was put down at long to extreme ranges and proved effective and surprisingly accurate. The parachuting officers of 2nd Forward Observer Unit were in communication by wireless with their supporting regiments in time that varied from 15 to 40 minutes after landing".

Varsity also saw the destruction and disposal of a massive amount of gliders (only 24 returned in serviceable condition out of 440), which helps to explain why none exist today wholly intact.

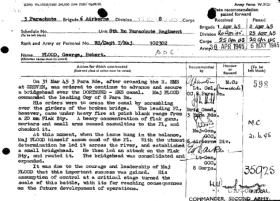

The day after the Operation was spent consolidating positions and defending against enemy counterattacks. To begin with, on the night of March 24/25, large numbers of Germans were still trying to escape through the 3rd Parachute Brigade's positions in the Diersfordt wood. Moreover, four German tanks and supporting infantry launched a counterattack against the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, but it was quickly driven off. 6th Airlanding Brigade was confronted with a larger counteroffensive during the same night at 0230, when Germans attempted to rush the bridge near Ringenberg. 2nd Battalion, Ox and Bucks, was granted permission to blow the bridge, which happened at around 0240. Their positions were also infiltrated after dawn and nearby buildings were set alight. It took most of the day to drive out the infiltration. 1st Battalion, Royal Ulster Rifles fought off two German tanks advancing on another bridge at 0730, completely destroying one and heavily damaging the other. Moreover, close air support from the RAF destroyed an estimated 12 targets on March 25. At 1045, reinforcements arrived in the form of a squadron of amphibious Duplex-Drive tanks and a battery of self-propelled guns. These were deployed on the captured bridges along the Issel.

On March 26, 6th Airlanding Brigade was given its new task of capturing high ground north west of Brunen, the next town east of Hamminkeln. Two enemy companies were defeated in the ensuing battle, with the objective taken by 1345, and 180 POWs secured. 6th Airlanding Brigade entered Brunen that night, finding it empty. By March 28, 5th Parachute Brigade had captured the village of Erle, nearly ten miles east, along with 200 POWs.

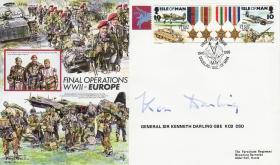

Thereafter the rapid advance across Germany began in earnest. Particular urgency was placed on reaching Wismar before the Russians, as the Allies had received intelligence that the USSR intended to permanently occupy Denmark in defiance of the Yalta agreement. Indeed, they occupied the Danish island of Bornholm for 10 months after the war. Moving nearly 300 miles, 6th Airborne Division's main body reached Wismar at 1200 on May 2, just four hours before the Red Army arrived. Otway describes the advance:

"Since 29th March, the Division had covered about 300 miles, which is roughly the distance between Lembeck and Wismar...An overall speed of advance of 11 miles a day was achieved from the Rhine to the Elbe, after which it increased considerably. The original instructions to maintain the speed of the advance at all costs had been fully carried out, and the momentum originally gained was never relinquished".

James Hill's 3rd Parachute Brigade met the lead formation of Marshal Rokossovsky's 70th Armoured Division at Wismar at 1600 hours on May 2, just 39 days after dropping in. Looking back on Varsity, the official account states,

"The lessons taught by previous bloody, hard-fought battles had been well and truly learned, and the airborne troops had gone into action tied closely in terms of time and space to the army on the ground. The result was victory, unadulterated and complete...Here the story of the exploits of the 6th Airborne Division must end, at the moment of their greatest triumph".

Battle Honour Conferred:

Rhine

This article is currently under development

Compiled with information from:

The Second World War 1939-45, Airborne Forces (1951), Lt-Col. T.B.H Otway.

6th Airborne Division Ops. Orders, Operation Varsity, March 1945

Narrative of Operation Varsity 24 March 1945 (Written 31 March 1945 by author with initials KWO)

Operation "Varsity" Summary of aircraft (1945)

The Race for the Rhine Bridges (Ebbw Vale, 2001) Alexander McKee

Airborne Warfare: New Edition, Lieutenant-General James Gavin

"Over the Rhine", The Last Days of War in Europe, Brian Jewell

By Air to Battle, the Official Account of the British Airborne Divisions (London, 1945)

Article rewritten by Alex Walker 14/03/2024

Latest Comments

There are currently no comments for this content.

Add Comment

In order to add comments you must be registered with ParaData.

If you are currently a ParaData member please login.

If you are not currently a ParaData member but wish to get involved please register.